By World Wide Fund for Nature

The monetary value of nature is estimated to be around US$125 trillion in which half of the world’s GDP amounting to US$44 trillion is highly dependent on it and potentially exposed to risk from nature loss. Around 1.2 billion jobs in the nature-related sectors such as farming, fisheries, forestry, and tourism are dependent on the effective management and sustainability of healthy ecosystems.

However, climate risks and biodiversity loss are becoming more significant in the age of the Anthropocene, evidenced by the growing economic and financial losses impacting businesses, financial institutions, governments, and society. In Malaysia alone, more than 50 natural disasters in the past 20 years have resulted in over RM8 billion losses with more than 3 million people affected through displacements, injuries, and death. Businesses such as Pacific Gas & Electric, a public utility company with US$20 billion market capitalisation in the US, filed for bankruptcy in 2019 due to lawsuit cases by the victim of wildfires sparked by one of its facilities. The non-performing loan ratio of representative coal-fired power companies is estimated to exceed 20% by 2030 due to a decline in demand and a drop in clean energy costs.

There is an investment gap of US$2.5 trillion every year to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. For preserving and restoring ecosystems alone, only US$52 billion is being invested out of US$300 billion to US$400 billion that is required. Public funds alone are insufficient to fill this gap. This is aggravated by the perception of the private sector that nature conservation projects are relatively unattractive due to low financial return.

Bankable Nature Solutions (BNS) might be an answer to this quest as it promotes nature conservation and offers a comparative financial return. BNS can be understood through three dimensions namely (1) environmental and social sustainability, (2) business viability, and (3) fundability. First, BNS aims to reduce negative pressure on ecosystems, drive resilience and sustainability for humans and nature. Second, BNS seeks to generate positive returns for communities, businesses, and investors. Third, through blended finance, BNS creates an enabling environment for private investors and catapults public and philanthropic funds towards a financially self-sustaining approach.

BNS Project Case Studies

There is a growing number of business and investment opportunities associated with maintaining, preserving, and restoring nature through structured, blended, and project finance. A global survey of 168 financial institutions, asset owners, and asset managers demonstrates that investment in natural capital could reduce risk, boost the resilience of investment portfolios and enhance their reputation. The following highlights the financial structure and positive impact of two BNS projects in Turkey and Greece.

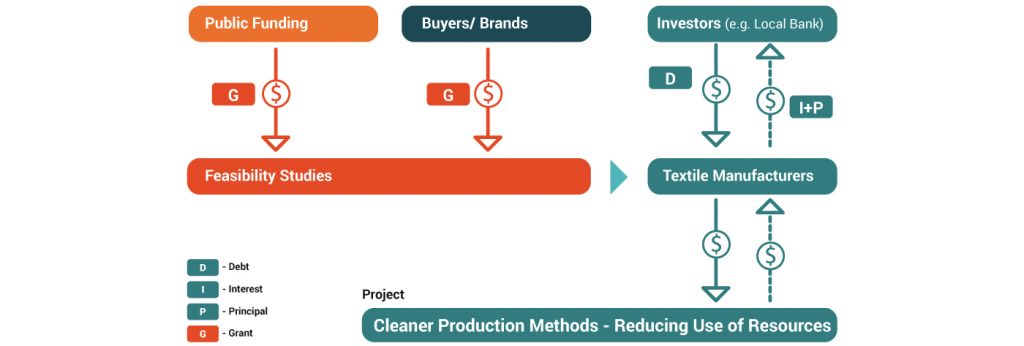

The Buyuk Menderes River Basin project in Turkey (Diagram 1) aims to improve the water quality in the river basin to ensure clean water supply for the community. The project supports the textile company in adopting a cleaner production process that uses less water, chemicals, and energy and reduces solid waste and waste water. It is made possible from a combination of (1) grants to undertake feasibility studies, (2) loan from local banks to finance the cleaner production methods (EUR5 million to EUR12 million with six-months to two-years payback period), and (3) commitment from fashion brands to buy from manufacturers which fulfill the Higg index. As a result, there were savings from EUR4 million to EUR12 million annually, saving 1.5 million cubic meters of water and mitigating at least 20% negative impact on water quality.

Another insightful example is the green infrastructure for the urban resilience project in Athens. The municipality of Athens received a EUR5 million loan from Natural Capital Financing Facility (NCFF) to enhance the resilience of the city against climate change impact by reducing urban temperature, mitigating urban heat island, and increasing water infiltration as outlined in the Athens Resilience Strategy for 2030. The financing facility is accompanied by a technical assistance grant amounting to EUR500,000 to redesign urban spaces in Athens, including the restoration of parks, public squares, streets, revitalisation of Lycabettus hill, among others.

Funding Facilities Case Studies

There have been a number of funding facilities around the globe to facilitate bankable nature projects. The NFCC is a partnership programme between the European Investment Bank and the European Commission to facilitate conservation and nature-based solution projects. This is structured through a flexible financing facility (debt and equity funds between EUR2 million and EUR15 million backed by an EU guarantee) and technical assistance (including a grant up to EUR1 million) to support sustainable projects. Several funding facilities are supported by the NCFF such as the Irish Sustainable Fund (EUR12.5 million) on sustainable forestry and Rewilding Europe Capital (EUR6 million) in supporting nature-focused business in Europe.

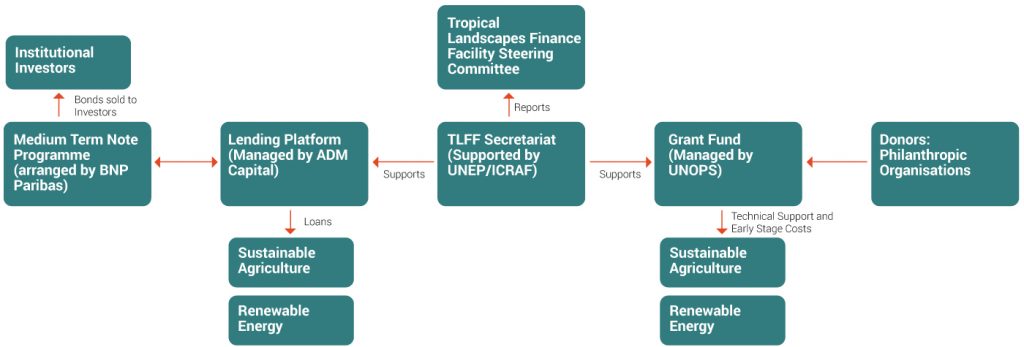

The Tropical Landscapes Financing Facility (TLFF) (Diagram 2) in Indonesia is the first private landscape financing initiative by the government of Indonesia supported by the UN Environment Programme, World Agroforestry Centre, ADM Capital, and BNP Paribas. The initiative was launched in 2016 leveraging public funding to mobilise private finance for projects that foster green growth (biodiversity, forest management, ecosystem restoration, and renewable energy projects) and enhance rural livelihoods. TLFF have two funding channels, namely a lending platform and a grant fund. The lending platform offers a long-term loan which could be securitised through the medium-term note programme, while the grant fund provides technical assistance and co-funds early-stage development costs.

Potential of BNS in Malaysia

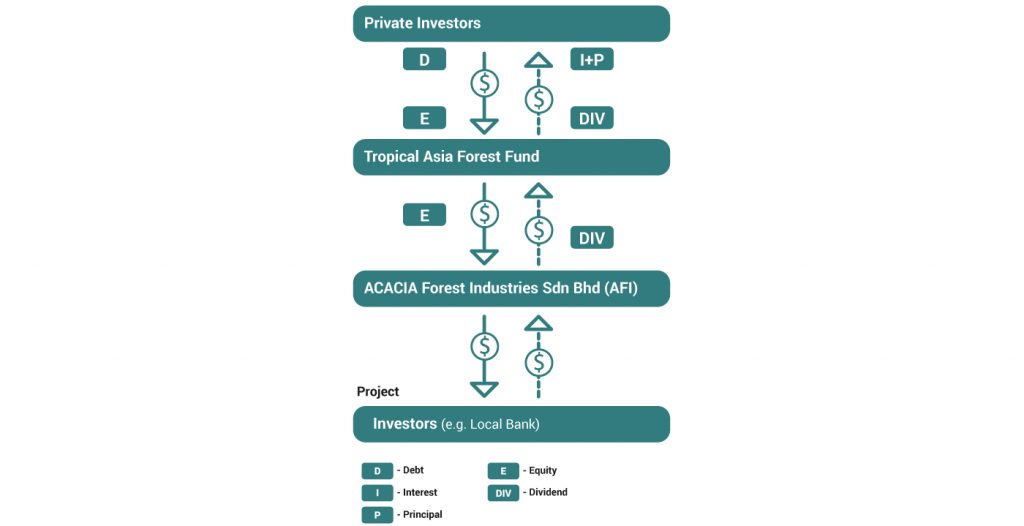

One of the BNS projects that has been developed in Malaysia is the Acacia Forest Industries (AFI) project in Sabah funded by Tropical Asia Forest Fund (Diagram 3) through close-ended private equity. The project aims to introduce sustainable forestry management practices and make AFI a major certified eucalyptus producer in the region. The project created positive impact on the landscape, including 2.5 million seedlings planting per year, 25,000ha area planted with timbers, and half the area allocated for conservation and livelihood improvement. Cash flow is generated from the sales of mature Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified timber at a premium price, sales of latex, and carbon revenue.

Given Malaysia’s biodiversity, climate, and livelihood conditions, there are several potential projects that can be catalysed into BNS. For example, the Kedah Sustainable Landscape Initiative (KSLI). Comprising eight forest reserves, the Ulu Muda Forest Complex (approximately 164,000ha) is a vital water catchment forests for three northern Peninsular states of Kedah, Penang, and Perlis, providing water provisioning services to more than four million people, enabling economic development, and contributing to the nation’s food security. KSLI is an integrated landscape approach that looks beyond the scope of a single sector stakeholder group and looks at the scale of a land management unit to meet the needs of diverse stakeholders and sectors. Among the activities of the projects include:

- Establish a protected areas system and framework in Kedah to protect biodiversity and vital ecosystem services;

- Forest restoration and certified management for the purposes of rehabilitating vital ecosystem services and to ensure ecological connectivity to the Central Forest Spine;

- Establish a high-end tourism operation that models circular economy, regenerative practices, supports biodiversity research, and provides a sustainable livelihood to the local community; and

- Adoption of sustainable practices in paddy farming.

In the Baleh watershed, an integrated watershed management (IWM) approach is being advocated as a pilot project in Sarawak. The project aims to improve watershed management and governance which will result in increased protection of water catchment forests for water supply, rivers and its freshwater ecosystems, secure habitats for wildlife, improve water quality for communities and protect economic investments. A Baleh Wildlife Connectivity area is located within this watershed, connecting key national parks within Sarawak to the large national parks of Betung Kerihun and Kayan Mentarang in Kalimantan, Indonesia.

The project will involve joint efforts from government agencies and private sector to build capacity on IWM, to improve ecological and environmental information that will help in more informed decision-making, and establishing alternative financial support for areas set aside for water and species protection. There is also a large hydropower project to be constructed in the area. WWF-Malaysia provides the lead technical support, convening multi-stakeholders, capacity building on IWM, work with communities for the river, fish, and livelihood protection, respective studies for environmental and alternative finance potential for protected areas.

Conclusion

Participation of stakeholders from banks, investors, civil societies, and the government is crucial in moving forward the climate and nature-based solution in Malaysia:

• Funders

Funders may support BNS projects through different financing schemes. Among them are traditional loan, result-based payments financing (e.g. The Livelihoods Investment Fund in Sustainable agroforestry dairy project in Mount Elgon, Kenya), sustainability bond (e.g. bond for TLFF-PT RLU project arranged by BNP Paribas), blended finance (e.g. As-Samra waste water treatment plant financing led by Arab Bank together with public funding from the United States Agency for International Development, Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the Jordanian government), and soft loan with an interest rate below market return (e.g Fairventures Social Forestry project in Indonesia).

In tapping into BNS, the funders may leverage the growing technology and dynamic tools that can gather data and evaluate the impacts of the projects. Satellite imagery and remote sensing data can monitor environmental indicators such as forest cover changes. For instance, the Global Forest Watch Pro tool is used by Inter-American Development Bank in Paraguay to detect deforestation.

There are also numerous opportunities in BNS by supporting the net zero-emission goals of the corporations. Locally, Petronas is the first oil company in Asia aiming to be carbon neutral by 2050. One of its strategies is to invest in nature-based solutions that preserve and restore the capacity of ecosystems to act as forest-based carbon sinks for CO2 sequestration. There is an opportunity for collaboration in projects that support key conservation measures such as reforestation, community empowerment, and co-management.

• Business-Funder Platforms

The lack of centralised platforms to stimulate and match businesses and funders may stunt the growth of sustainability ventures. Efforts should be initiated by intermediaries such as business associations/business chambers to establish credible online platforms that connect sustainable buyers, suppliers, and funders. To accelerate the transition, sustainability standard owners from different industries (such as B corporation, Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, Forest Stewardship Council, Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification, Aquaculture Stewardship Council, etc) could be included to facilitate direct consultations and technical advice. Such a platform could be a channel for sustainability-based producers to secure offtake from big brands and allow big brands to address their traceability issues in maintaining their sustainable value chain. The offtake mechanism also enhances the financing options for sustainable projects.

A centralised platform also allows better ideas and information exchange which is crucial to accelerate sustainability and facilitate innovation in business and conservation programmes. Resource sharing to facilitate innovation in the business and conservation programmes could help businesses better account for their impact and dependencies on biodiversity and natural capital.

• The Government

Through innovative arrangements with multilateral financial institutions, the government can seek technical assistance funds to support the generation of ideas and co-fund early-stage development costs. For instance, the government of Indonesia and the Global Green Growth Institute’s (GGGI) Green Growth Program helps to develop and enable bankable projects. GGGI serves as the facilitator in bringing together various relevant stakeholders, including the government, international and national investors, and project developers to stimulate green capital flows.

Apart from multilateral financial institutions, UN agencies such as Food and Agriculture Organization support countries with tools and technical assistance to establish innovative and inclusive domestic finance mechanisms for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) and land-use investments. Environmental fiscal transfers provide financial support such as tax deduction for green projects and investment to attract investors and funders (e.g. tax deduction on socially responsible investment sukuk in Malaysia) and first-loss guarantee scheme for bankable green projects should also be replicated and scaled up.

Thiaga Nadeson is the Head of Markets and Education at WWF-Malaysia with more than 18 years of experience in environmental education, community engagement education, public sector partnership and sustainable finance initiative.

Dr Adam Ng is Sustainable Finance Expert at WWF-Malaysia and a member of the CFA Institute Asia-Pacific Research Exchange Society Engagement Committee.

Katherine Lim is Manager for Sustainable Finance Engagement at WWF-Malaysia focusing on sustainable finance and managing the International Climate Initiative grant deliverables.

Siti Rizkiah is Sustainable Finance Analyst at WWF-Malaysia focusing on ESG and sustainable finance.

Norizan Mohd Mazlan, Sharon Lo, and Belinda Lip, who enriched the article through contributing case studies from Malaysia.