Winning the Battle and the War

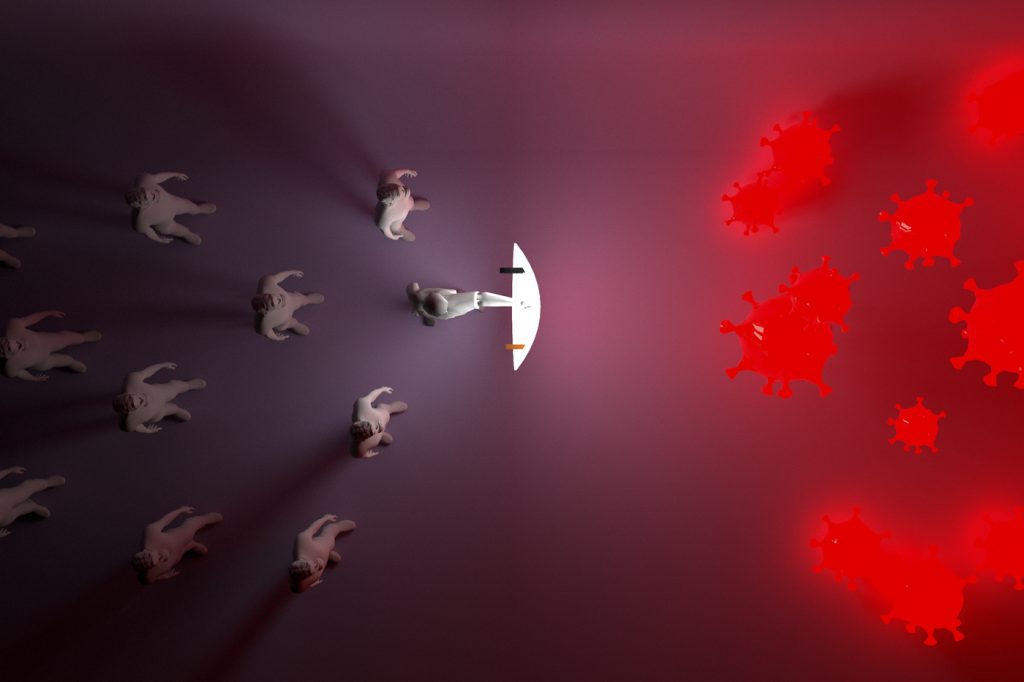

Wresting fatigue determines whether this crisis marks your finest hour or the darkest day.

Wresting fatigue determines whether this crisis marks your finest hour or the darkest day.

By Angela Yap Siew Peng

Make no mistake, war-room fatigue is real and dangerous.

After almost a year since the outbreak, many teams are still on the ground 24/7. Top-of-mind are two mantras: protect the health of employees and customers, and ensure business continuity.

In pursuit of these objectives, command-and-control centres have been set up comprising key operational talents with a remote or on-site global view of the situation. These responders are technically empowered to plan and execute the ‘tough calls’ needed to manage the crisis at hand.

Welcome to banking’s war room, a Lean Six Sigma practice touted as the solution to our crisis-management age. Governments use it, regulators have deployed it, and many corporates swear by it.

Whether the objective is to cost down, provide liquidity for survival, or retool the business for the impending recovery, every established management consulting firm extols its virtues. Yet, just like post-traumatic stress disorder for soldiers in combat, few talk about the long-term effects of war room and crisis management on the psyche and well-being of people who work under high-stress conditions.

Adopted from the military practice of establishing bunker-like operational hubs where generals and strategists exchange by-the-minute reports and plan tactical manoeuvres, war rooms have been deployed for decades among project management professionals tasked with resourcing and executing critical programmes such as change management.

In the business world, the war room is no place for the faint-hearted. More than just a term to be bandied around, setting up a war room is not a guarantee that one will emerge unscathed. The real game-changer is the mindset shift that accompanies it. In the context of today’s risk-ridden world, banking’s war room – whether to address cybercrime or navigate a crisis – must be populated with individuals who thrive on the adrenaline and are confident to make rapid-fire decisions.

Almost all banks today have working war rooms in place, but typical project war rooms are highly intense and supposed to last only a period of two or three weeks. With Covid-19, some banks, especially in Asia where many of the earliest responders are situated, their war rooms have been operational for months.

In a May 2020 article published by Harvard Business Review, prominent business psychologist Dr Merete Wedell-Wedellsborg warns: “I see this war-room fatigue in the leaders right now — and in their teams. It’s real and it is infectious, and it hits you like a hammer from one day to the next.”

Her feature, If You Feel Like You’re Regressing, You’re Not Alone, documents the surreal and cyclical experience of leaders who have yet to manage a bigger crisis than Covid: “In my experience as a psychologist and executive advisor, I’ve found that crises follow a rough pattern: Emergency. Regression. Recovery.”

An understanding of the symptoms that demarcate each phase helps leaders and team members identify their current state and hopefully circumvent a meltdown.

Dr Wedell-Wedellsborg writes: “In the beginning, when the emergency becomes clear, team energy rises, and performance goes up. Almost all of us have unknown reserves. As the executives’ experiences reflect, this reaction feels full of purpose and much gets done. Leaders tend to become the best version of themselves in this phase and teams instinctively pull together and become highly productive. Few people question the leaders’ authority, and teams work in hectic, but harmonious, ways. The urgency created by the shock paves the way for rapid decision-making and turbocharges teams’ bias for action.

“Then the second phase hits: a regression phase, where people get tired, lose their sense of purpose, start fighting about the small stuff, and forget to do basic things like eat or drink — or they eat and drink too much.

“The concept of regression comes from developmental psychology and describes how people roll back to a less mature stage when faced with pressure. Regression is one of the mind’s ways to defend itself from confusion and insecurity by retreating to an emotional comfort zone.

“From combat psychology in particular, we know that regression is the most dangerous phase for teams. The most stressful events for soldiers don’t actually involve dangerous missions that require courage and action. They actually involve waiting: being in the middle of nowhere on a post, repairing equipment and handling administrative tasks, not being able to use their particular skills. It turns out that boredom, lack of new experiences, and monotony can be much more stressful than combat.

“The regression phase is uncomfortable. It’s also unavoidable and cannot be skipped. Understanding what the phases looklike and how you can move through the toughest part of crisis will help you mitigate the performance drop.

“The challenge for leaders is to pull through the regression phase in a constructive way and get to the recovery phase to reopen, rebuild, and prepare for the future.”

What can leaders do to successfully transition to the recovery phase after fatigue has set in for both themselves and their teams?

Ronald Heifetz, one of the world’s foremost authorities on leadership, and his colleague Marty Linsky, professor at Harvard University Kennedy School of Government, advise that leaders take what they’ve termed ‘a balcony perspective’ and ‘go long’ in their vision whenever teams go off tangent:

They propound: “The ability to maintain perspective in the midst of action is critical to lowering resistance. Any military officer knows the importance of maintaining the capacity for reflection, especially in the ‘fog of war’. Great athletes must simultaneously play the game and observe it as a whole. We call this skill ‘getting off the dance floor and going to the balcony’, an image that captures the mental activity of stepping back from the action and asking, “What’s really going on here?”

The emphasis that leadership is “an improvisational art” is comforting, especially when it is too often simplistically packaged as a neatly prescribed science. Truth be told, even Peter Drucker’s golden maxim of managing by walking around won’t do much good if one lacks the responsive qualities expected of a leader.

In an era obsessed with quantifying of everything, it is empowering – indeed, liberating – when overwhelmed leaders are told that there is no moment-to-moment script when wading in unchartered waters. There is only the belief in vision, values, and dedication to see things through.

“You must respond as events unfold. To use our metaphor, you have to move back and forth from the balcony to the dance floor, over and over again throughout the days, weeks, months, and years.

“While today’s plan may make sense now, tomorrow you’ll discover the unanticipated effects of today’s actions and have to adjust accordingly. Sustaining good leadership, then, requires first and foremost the capacity to see what is happening to you and your initiative as it is happening and to understand how today’s turns in the road will affect tomorrow’s plans.”

Premier Jacinda Ardern’s lockdown strategy for New Zealanders was simple: Go hard, go early. For banking, we recommend you add “go back to the drawing board” in your arsenal toolkit for crisis survival.

The ultimate goal of responsive leadership is resilience, the goal that banking has been preparing itself for almost a decade since the global financial crisis (GFC). The words may be different but the message is the same: stay clear of a SNAFU (the military acronym for ‘Situation Normal All F*&%#d Up”).

War-room strategies may win you the battle, but not necessarily the war. Post-GFC, just as the then Bank of England Governor Mark Carney urged G20 policymakers not to give in to the stress of “reform fatigue”, modern-day war rooms must be ever vigilant of signs of crisis fatigue in their workforce and pre-empt its damage to morale, performance, or in some cases, survival.

Next time, before you log in to that virtual meeting room or email a client, do a quick mental check to make sure you’re in the right headspace. If not, take a moment, perch ‘on the balcony’, and breathe. As a friend once told me, a change of view is as good as a holiday.

Then, when you’re ready, strap on those combat boots…and go.

HOW BANKING’S WAR-ROOM MINDSET BUILDS OPERATIONAL RESILIENCE

The military sharpens soldiers’ skills with large-scale combat drills like Jade Helm and Foal Eagle, which send troops into the field to test their tactics and weaponry. The financial sector created its own version: Quantum Dawn, a biennial simulation of a catastrophic cyber strike.

In the latest exercise in November, 900 participants from 50 banks, regulators and law-enforcement agencies role-played their response to an industry-wide infestation of malicious malware that first corrupted, and then entirely blocked, all outgoing payments from the banks. Throughout the two-day test, the organisers lobbed in new threats every few hours, like denial-of-service attacks that knocked the banks’ websites offline.

The first Quantum Dawn, back in 2011, was a lower-key gathering. Participants huddled in a conference room to talk through a mock attack that shut down stock trading. Now, it is a live fire drill. Each bank spends months in advance recreating its internal technology on an isolated test network, a so-called cyber range, so that its employees can fight with their actual tools and software. The company that runs their virtual battlefield, SimSpace, is a [US] Defense Department contractor.

Sometimes, the tests expose important gaps.

A series of smaller cyber drills coordinated by the Treasury Department, called the Hamilton Series, raised an alarm three years ago. An attack on Sony, attributed to North Korea, had recently exposed sensitive company emails and data, and, in its wake, demolished huge swathes of Sony’s Internet network.

If something similar happened at a bank, especially a smaller one, regulators asked, would it be able to recover? Those in the room for the drill came away uneasy.

“There was a recognition that we needed to add an additional layer of resilience,” said John Carlson, the chief of staff for the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center, the industry’s main cybersecurity coordination group.

Soon after, the group began building a new fail-safe, called Sheltered Harbor, which went into operation last year. If one member of the network has its data compromised or destroyed, others can step in, retrieve its archived records and restore basic customer account access within a day or two. It has not yet been needed, but nearly 70% of America’s deposit accounts are now covered by it.

Source: Extract from Banks Set Up War Rooms, Adopt Military-style Tactics to Fight Cybercrime, The Seattle Times, November 2018.

Angela Yap Siew Peng is a multiaward-winning entrepreneur, author, and writer. She is Director and Founder of Akasaa, a boutique content development firm with presence in Malaysia, Singapore, and the UK and holds a BSc (Hons) Economics.