Data Ethics: Time to Get Your House In Order

Landscaping what’s fair and responsible use in emergent banking tech.

By Dr Amanda Salter

The technophiles among us are well aware of the recent high-profile cases of algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) gone wrong.

Take the ignominious Apple credit card. Launched in 2019 in the US and backed by a leading global bank, the offering was panned by consumers who noticed that, as a result of its credit-rating algorithm, women were offered significantly lower lines of credit than men who had similar income and assets. The subsequent media storm sparked an ongoing investigation by the state regulator, who stated that “any algorithm that intentionally or not [emphasis added] results in discriminatory treatment of women violates [the] law”.

The fracas highlights the common fallacy that technology, algorithms, and data are clean, objective, and neutral. This perception is patently untrue. All algorithms and data carry the biases of the people and the cultures that collect, process, analyse, and present that data.

A solid, long-term data ethics programme can forestall harmful and costly impacts, mitigating risks so that banks won’t be caught with their pants down.

Researchers Luciano Floridi and Mariarosaria Taddeo, in a 2016 Royal Society Journal article, classify “data ethics as a new branch of ethics that studies and evaluates moral problems related to data (including generation, recording, curation, processing, dissemination, sharing and use), algorithms (including artificial intelligence, artificial agents, machine learning and robots) and corresponding practices (including responsible innovation, programming, hacking and professional codes), in order to formulate and support morally good solutions (e.g. right conducts or right values).

The nascent field of data ethics is constantly evolving. There are many societal and technological drivers behind the need for data ethics, from the rise of big data to the Internet of Things, and of course, AI itself.

We could argue that right now, our capabilities are only limited by our ambition and our expectations. But to misquote a phrase by Dr Ian Malcolm, the iconic scientist in the sci-fi classic Jurassic Park, just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should – ability doesn’t mean prerogative. In the emerging field of AI there is often no clear-cut right or wrong answer, and the mere presence (or absence!) of data can create new ethical or moral dilemmas which need to be addressed.

Many organisations around the world are working hard to draw clear lines in the shifting sands. Much progress has been made in the last three years, summarised below.

In 2019, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development published a set of five principles for the responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI. All are intrinsically linked to data governance and relevant to financial services:

Asia-Pacific countries which have signed up to these ethical principles include Australia, Korea, Japan, and New Zealand. Other principles and guidelines echoing similar sentiments have also been published by such disparate global groups as the Open Banking Standards in the UK, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and the Open Data Institute (ODI).

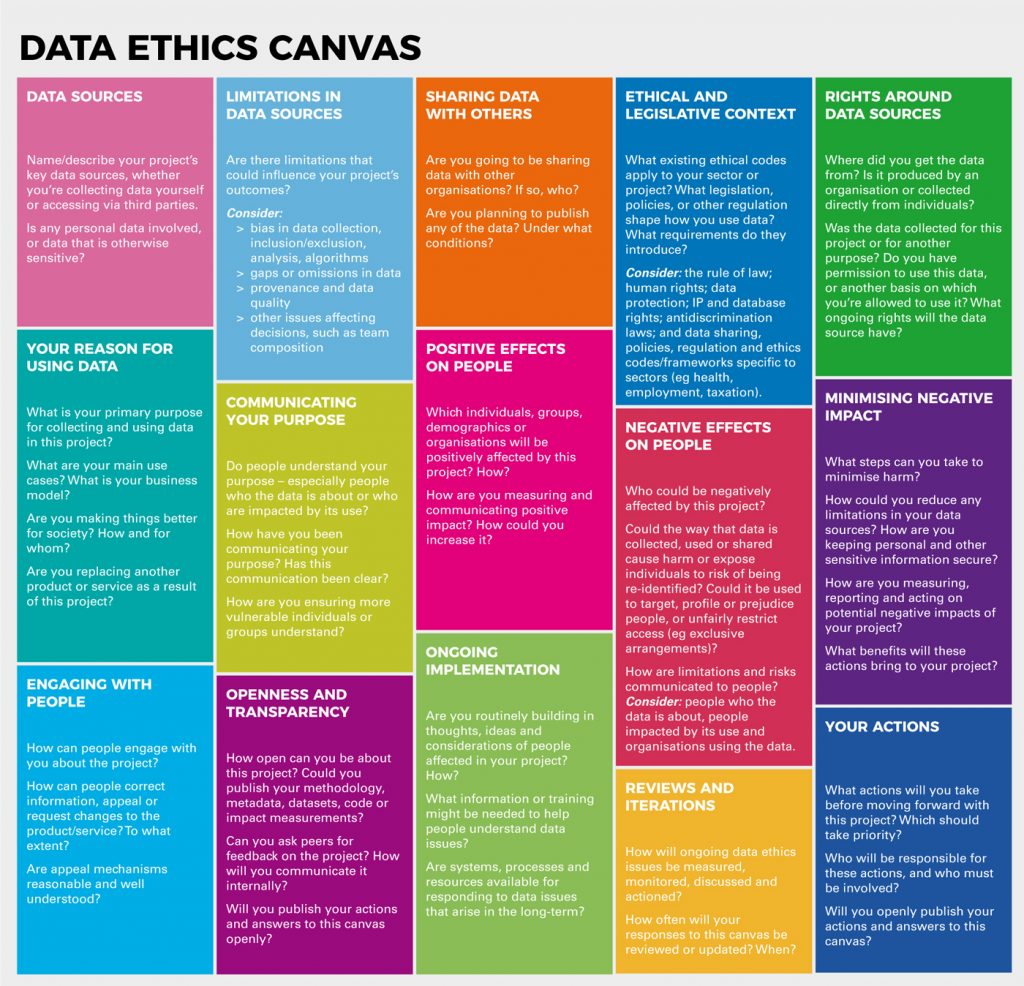

The ODI also published the Data Ethics Canvas (see Figure 1) in 2019. This tool helps projects and organisations identify and manage ethical data issues and gives a framework for putting good practices in place around the ways data is collected, used, and shared.

Closer to home, the Japanese government’s enthusiasm for all things AI, robotics, and big data meant they were one of the natural early movers in the field. Japan first published the Draft AI Research & Development Guidelines in 2017, followed by a set of seven core human-centric AI principles in 2018 that aim to reduce risks associated with such systems by establishing transparency and accountability processes for corporates who make decisions using AI.

Singapore followed suit, establishing an Advisory Council on the Ethical Use of AI and Data in 2018. Infocomm Media Development Authority, a statutory board under the city state’s Ministry of Communications and Information, went on to publish the Model AI Governance Framework, the second edition of which was launched at the 2020 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting. Both DBS and HSBC have featured in a compendium of use cases which demonstrate how the framework could be effectively implemented in a banking context.

In 2019, the Hong Kong Association of Banks working with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) launched an Ethical Accountability Framework for fintech development, including supporting models for data impact and process oversight. The HKMA also runs training programmes tailored to help banks adopt the framework and models in the development of fintech products and services.

So, what do banks need to consider in light of the principles of good data ethics? The list of banking practices that would be potentially impacted by a data ethics assessment include, in no particular order of priority:

Banks need to question the ethics of each of these applications of algorithms and data, and reexamine them in light of data ethics principles. This may well result in the tightening up of data governance or processes, leading to reduced risk further down the line. Many banks have appointed Chief Data Officers to lead the way and there is a need for dedicated resources to keep on top of the changes in technology and data governance practices to ensure banks stay on the front foot.

UK Finance, the trade body for its banking and financial services sector, published a report in March 2019 that summarises three types of risk associated with the above practices – legal and regulatory risk, operational risk, and reputation risk. In its report, Ethical Use of Customer Data in a Digital Economy, unfair algorithmic bias, opaque restrictions of customer choices, skills shortages, and data security stand out as the most challenging risks to address.

Despite the risks of running headlong into an Apple Card-like scandal, the reward for banks that get it right is huge. A 2020 report by the Netherlands’ Ministry of Economic Affairs & Climate Policy projects that by 2025, the AI global market would be worth up to EUR360 billion, and the Asia-Pacific region is anticipated to overtake North America as the primary player in the same timeframe.

In this light, banks should not view data ethics as a containing or limiting factor. There are many side benefits of applying data ethics well in the context of AI and big data and visionary Asia-Pacific banks can grab the opportunity to lead in this. Here are some potential ideas:

As banks enter a new era of big data and AI, we cannot shirk our responsibility to protect the public even as we chase down our gains. The power and peril of ever-increasing quantities of data is that the smallest decision made can have the power to materially impact peoples’ lives.

Banks who take the lead on data ethics make a statement that they put people, planet, and society’s best interests first. A focus on data ethics drives responsible and inclusive behaviour by ensuring that no one is unfairly disadvantaged by the data or algorithms that we steward. Proper consideration of data ethics is a gateway that can open up new responsible routes to benefits in this new territory.

Dr Amanda Salter is Associate Director at Akasaa. She has delivered award-winning global customer experience (CX) strategies and her recent guest lecture at the University of Cambridge shared insights from architecting impactful CX. Dr Salter holds a PhD in Human Centred Web Design, BSc (Hons) Computing Science, First Class, and is a certified member of the UK’s Market Research Society and Association for Qualitative Research.