Many Markets, One Common Language

Getting to a harmonised taxonomy in sustainable finance.

By Julia Chong

The sustainable finance landscape lit up in 2020.

According to research house Morningstar, assets under management in economic, social, and governance (ESG) funds leapt 29% to hit a record of nearly USD1.7 trillion in 2020. Reuters also reports that throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, ESG assets were a bright spot that bucked the capital flight trend into passive products as investors sought resilient investments that will perform better over time. Coupled with the global push to achieve the Paris Agreement climate targets, the creation of a common taxonomy for sustainable finance has gained renewed traction.

A taxonomy for sustainable finance is a comprehensive classification that defines whether or not an economic activity is environmentally sustainable. In the coming years, work in this sphere will be increasingly crucial for global investors, financial institutions, companies, and issuers in order to delineate between green (compliant), light green (transitioning), and brown (incompatible) activities.

+ Such taxonomies are a necessary step to

Some jurisdictions, like China, have moved to establish their own sovereign taxonomies, whilst in others like the EU, their taxonomies apply en bloc.

Just as a lingua franca – language that is adopted as a common language – facilitates global business, so too will financial markets benefit from a lingua franca in sustainable finance. The majors have since moved at record pace to unite on a comparable classification system for sustainable activities, one that will reflect the holistic principles of environmental sustainability and respect the diverse needs and views of each nation.

Note that as more jurisdictions move to regulate sustainable finance through national legislation, there will remain viable institution- and market-based guidelines and taxonomies, such as those set by the Climate Bonds Initiative or Common Principles for Climate Mitigation Finance Tracking, which are widely accepted and generally applied by issuers of green bonds and loans.

Progress in the following jurisdictions reflect the diverse taxonomic approaches:

> EU

In June 2020, the European Council issued the most definitive and progressive legislation for a unified classification system in sustainable finance. Dubbed the ‘EU Taxonomy’, it is formally published as Regulation (EU) 2020/852 (Taxonomy) and came into force on 12 July 2020. It plays a critical role in mobilising the needed EUR1 trillion in the next decade to achieve the EU’s goal of becoming the first carbon-neutral continent by 2050.

Financial institutions must comply with this Regulation in order to market their products – green/transition bonds, green credit, or green investment funds – as “environmentally sustainable as per EU legislation”. However, in line with legislators’ intent to not be overly prescriptive and to spur innovation in financial markets, a financial institution or corporate can still opt to issue a self-labelled transition bond as long it does not reference the EU Taxonomy or carry the words “environmentally sustainable” in its communications describing the product.

The EU Taxonomy harmonises classification standards for all member states, which in turn lowers the risk for green investors by removing cross-border barriers to fundraising and promoting uniformity in assets deemed environmentally sustainable. Activities are classified according to these six objectives:

This taxonomy is also a turning point as it introduces a multi-criterion framework through two principles – Substantial Contribution and Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) – as opposed to the unidimensional model of previous taxonomies. This means that an activity is deemed sustainable only when it proves that it substantially contributes to one of the abovementioned six EU objectives and does not negatively impact the other five EU objectives in the list. In this way, all objectives are interlinked, making it more stringent than any other current qualifying framework.

It also states that activities must comply with Minimum Social Safeguards (MSS), such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and the International Labour Organization conventions.

> China

The significance of a China taxonomy is underscored by its potential as the largest market for green goods and services, which Goldman Sachs puts at USD1 trillion.

As early as 2012, the People’s Republic issued its Green Lending Guidelines, which mandate banks report twice yearly on the loan balance, energy emissions, and water impact for credit granted under the following sectors: agriculture and forestry, energy and water saving, nature protection, ecological restoration and disaster prevention, waste disposal, recycling and pollution prevention, clean energy, rural clean water projects, green buildings, and green transportation.

Although implementation includes key performance indicators and reporting formats, the early guidelines fall short of establishing any explicit environmental criteria or thresholds. Loans which fulfil the green requirements and hold at least AA rating are eligible for preferred central bank refinancing terms.

In 2015, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) issued its China Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue to govern green financial bonds in six qualifying categories – energy savings, pollution prevention and control, resource conservation and recycling, clean transportation, clean energy, and ecological prevention and climate change adaptation.

The Catalogue, also known as the ‘China Taxonomy’, sets out specific qualifications for green projects or activities, the management of proceeds, and reporting guidelines. It details domestic industrial standards and regulations (including energy efficiency and pollution control) to be enforced on green bonds, but not on green loans.

In 2019, China released the Green Industries Guidance Catalogue, described by some as a “mini industrial plan” to further map out standards and policies to grow the green sector, develop the financial infrastructure to support green investments, and work to harmonise standards for sustainability.

By far the nation’s most extensive document to date, the Green Industries Guidance Catalogue is a collaboration between seven government bodies, including the National Development and Reform Commission, the PBOC, and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

> ASEAN

Although there are currently no national taxonomies on green finance or for sustainable financing, member nations, including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam, have outlined project categories which qualify for green financing.

In its 2019 Annual Report, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) called for financial institutions to treat climate risk on par with other types of financial risk as it “can also pose a systemic risk that could lead to a contraction in important financial activities that support the economy.”.

This view was reinforced by Mr Fraziali Ismail, Assistant Governor of the BNM, last October in a keynote speech which outlined the nation’s progress toward its own taxonomy: “We need to find a way to bridge the language and information gap between scientists, government and financiers. What science says about climate effects, what climate action the government is prioritising, what industries are providing and investing in – are quite incongruent at this point.

“In this connection, guidance for financial institutions to classify economic activities that contribute to climate change objectives is provided through our work in developing a principles-based taxonomy. This would be the start to build deeper understanding in climate risk, for financial institutions to better identify, assess and manage the risk. The Bank is now working to finalise the Climate Change and Principles-based Taxonomy, which is expected for issuance next year.”

Currently, the BNM-issued Value-based Intermediation Financing and Investment Impact Assessment Framework and its Joint Committee on Climate Change with the Securities Commission Malaysia drive the collective response to climate change. Islamic and conventional financial institutions have also stepped up by offering preferential financing rates for hybrid and green-certified properties and assisting oil palm smallholders in obtaining Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification.

Work is steadily streaming on all fronts.

In October 2020, the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF), announced that it had “initiated a working group on taxonomies that will work toward a Common Ground Taxonomy”.

The EU-backed IPSF is a multilateral forum for coordinated exchange and action for environmentally sustainable finance whilst respecting national and regional contexts. Its member states – Argentina, Canada, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Switzerland, and the EU – represent almost half of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“This Common Ground Taxonomy will enhance transparency about what is commonly green in member jurisdictions and contribute to scale up cross-border green investments significantly,” said the IPSF in its first annual report.

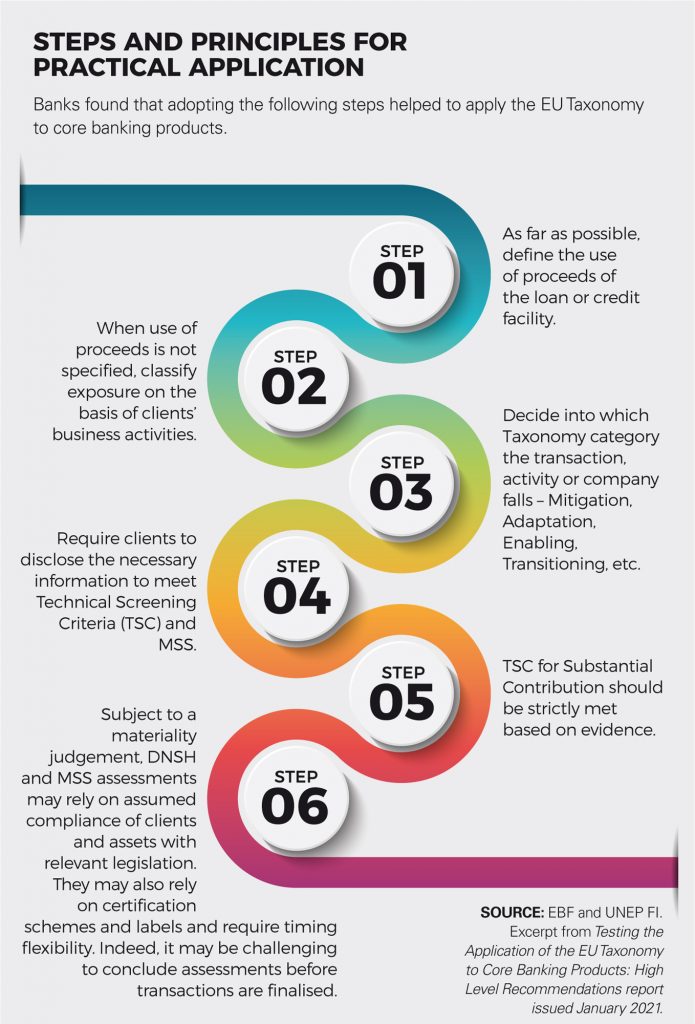

In January 2021, the European Banking Federation (EBF) and the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) released a joint report, Testing the Application of the EU Taxonomy to Core Banking Products: High Level Recommendations. It outlines the practical complexities of applying the EU Taxonomy to core banking products in a pilot comprising 26 major banks, seven banking associations, and five observing organisations.

Banks can expect substantial changes in the coming months and should keep abreast of the latest developments as countries develop and refine their respective legislations for sustainable finance.

Julia Chong is a Singapore-based writer with Akasaa. She specialises in compliance and risk management issues in finance.