Don’t Give Up on Happiness

Well-being may seem elusive, but necessity is the mother of invention. These new initiatives give hope.

Well-being may seem elusive, but necessity is the mother of invention. These new initiatives give hope.

By Dr Amanda Salter

Financial institutions have weathered the Covid-19 storm and emerged with a marked increase in empathy and better ability to handle extremely challenging emotional situations. On the customer side, banks have supported young people who lost their job and their income, and older people struggling with illness and increased healthcare bills. On the employee side, they have supported staff in a major upheaval of working practices, with all the mental health side effects that can come with this such as anxiety, stress, and depression.

I have seen first-hand how easy it is for someone to fall through the cracks. A close friend of mine was, as she thought, happily employed on a zero-hour contract (where the employer is not required to provide a minimum number of work hours). When lockdown kicked in, her employer’s workstream dried up. Promises of other work didn’t materialise. Her income disappeared and she was unable to pay her rent. She couldn’t access any of the government’s coronavirus impact funding because she had not been working with her employer for long enough. Her letting agent became threatening and refused to undertake essential repairs. She caught the virus before vaccines were available, recovered slowly, and is still occasionally battling fatigue. She is finally now back on her feet after a long and extremely stressful 24 months. This is a well-educated, experienced, financially prudent, hardworking, professional.

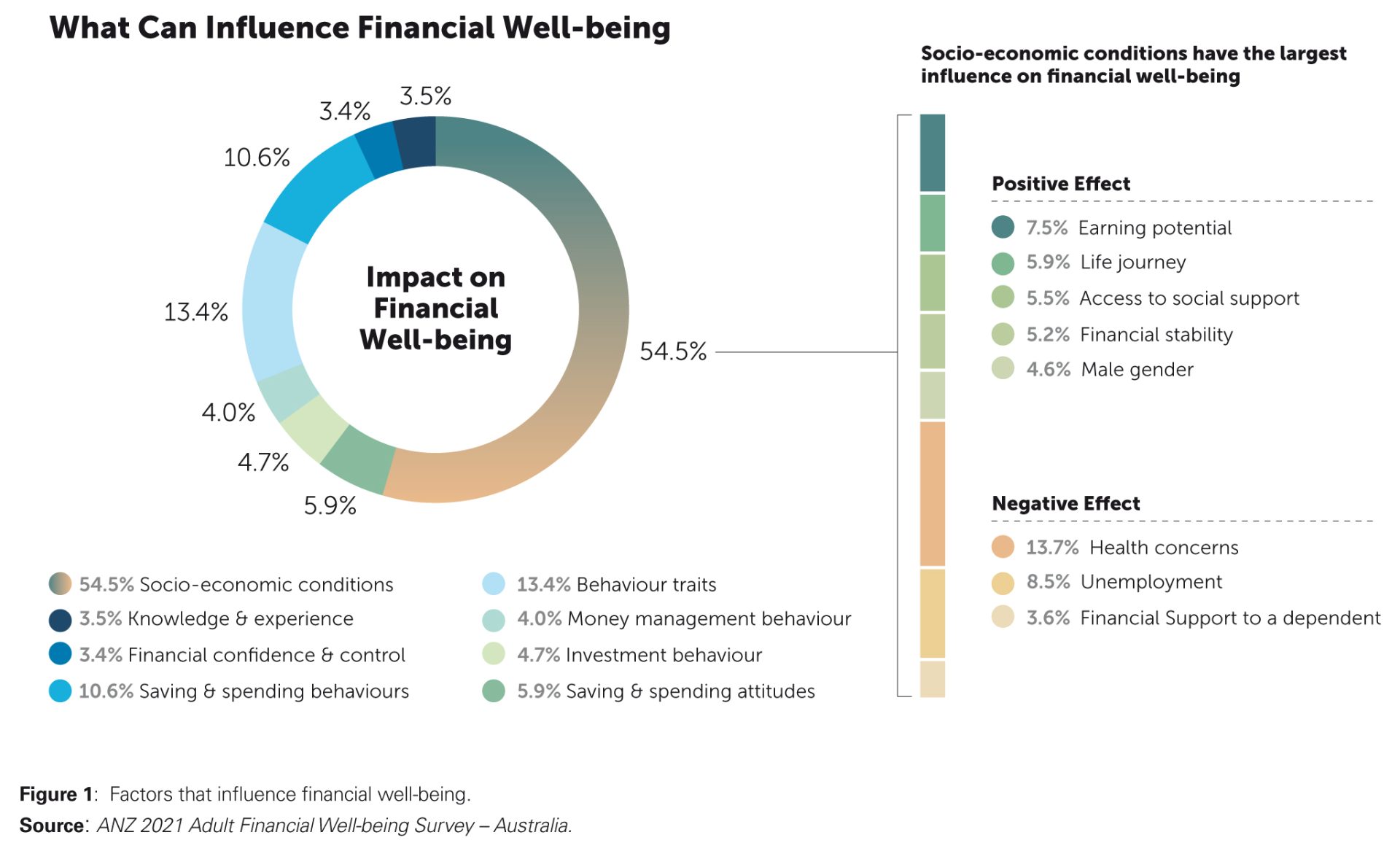

As a bank trying to reduce all these challenges down to a more manageable level, it may seem tempting to revert and focus purely on the financial aspect of well-being. Before you do this though, take a look at the latest ANZ research from December 2021. This study shows that the biggest factor influencing financial well-being of adults in Australia by far is socio-economic conditions.

Socio-economic factors, including health, unemployment, and earning potential, account for 54.5% of the variation in someone’s overall financial well-being, whereas behavioural traits such as impulsiveness, optimism, or frugality account for only 13.4% (see Figure 1).

The research challenges the common assumption that someone’s financial behaviour and knowledge make the most impact to their financial situation. In this view, financial well-being is holistic and co-dependent – many factors work together and if one is impacted, the entire boat is rocked. This research implies that we need to take a broad approach to well-being; explore initiatives to support physical and mental health, increase earning potential, and drive employment. To truly improve financial well-being, a preventative approach is needed to address these factors, instead of trying to shut the door after the horse has bolted.

With necessity being the mother of invention, many exciting initiatives and resources are moving the dial on well-being in this post-pandemic era. In particular, some tech-inspired innovations have addressed the broad spectrum of well-being highlighted by the survey. Below, we spotlight just a few examples:

Poor health is the most significant disruptor to financial well-being. Having an illness causes disruption to someone’s ability to work and leads to increased health costs – a double whammy. Even if someone is actively saving, and not borrowing to buy everyday expenses, a major health event can nullify the impact of these good behaviours.

This is a huge signal for banks to pick up on the preventative physical and mental health agenda, not only for their customers but also for their employees. New technologies in digital therapeutics and artificial intelligence (AI) already exist that can listen in on conversations and flag when someone is at risk of depression even if they may not realise it themselves. Health technology companies such as Sonde Health’s solution uses vocal biomarkers to score a person’s mental fitness and has been shown to be twice as accurate at detecting mental health issues compared to human practitioners.

This is life-saving technology and banks are well placed to use it. Banking systems facilitate millions of digital conversations every day, with both customers and employees. Every Microsoft Teams meeting and every customer-support webchat can already be automatically transcribed. We need only take one step further to feed these conversations through an AI and flag people who are at risk to hand them to the right support channel.

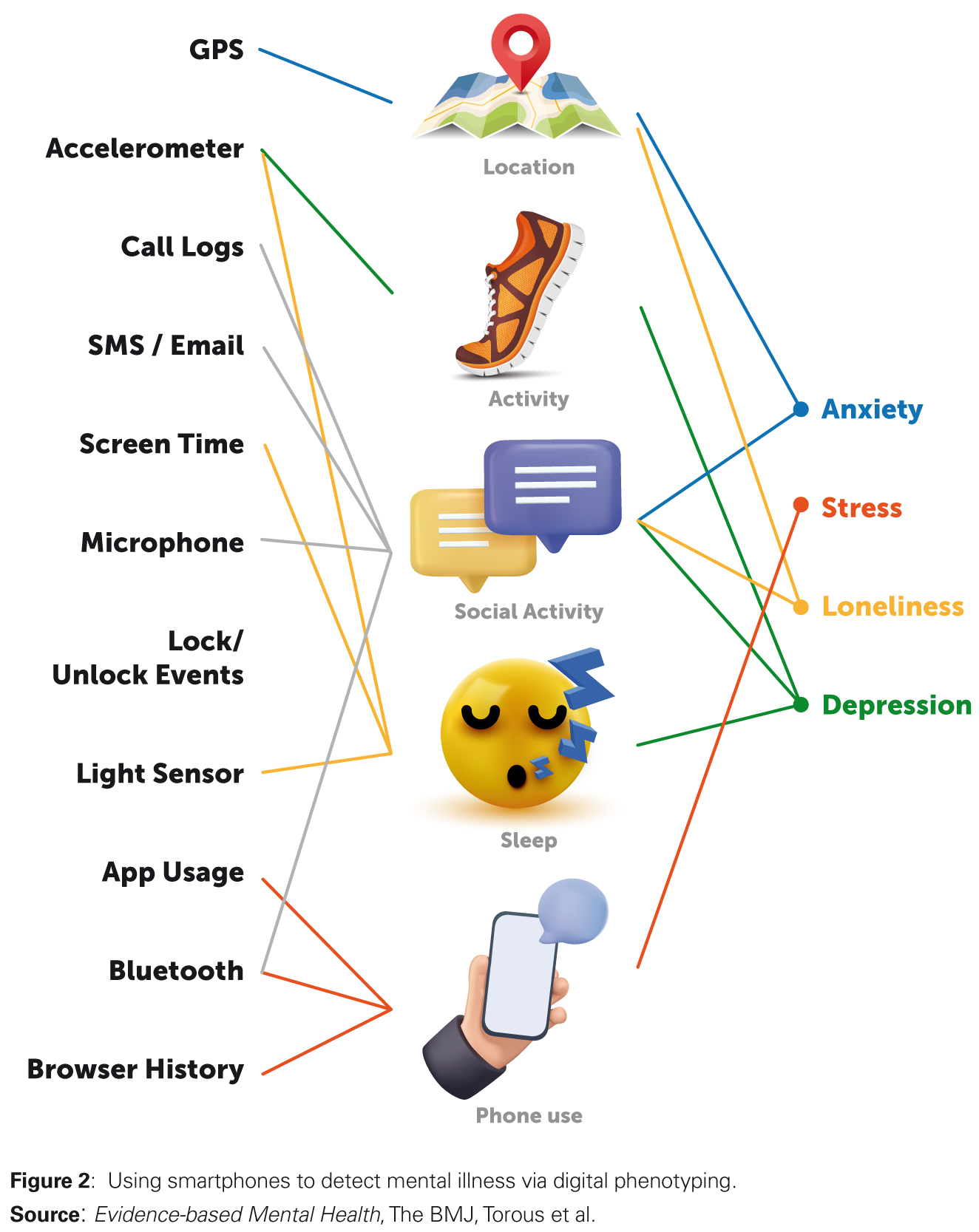

Another science called digital phenotyping uses smartphones and other wearable devices to capture data on a person’s behaviours, identifying symptoms relating to mental illness. The amount of screen time someone is using, their browser history, their activity levels, sleep patterns, exercise, and social interactions, are all data points that are used to build a picture of how someone is feeling (see Figure 2).

This data, coupled with statistical learning techniques, can indicate or predict an inclination towards anxiety, stress, loneliness, or depression. The model is not without its weaknesses, but the potential is huge. This makes it possible for an individual’s mental health to be monitored and assessed remotely, thus leading to more preventative, customised, and responsive care. Australia’s Black Dog Institute – a not-for-profit facility for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mood disorders – is using similar technology as part of their research to prevent suicide and improve workplace mental health.

Technologies such as these complement the range of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives by financial institutions such as HSBC Life, the insurance arm of the bank, whose latest move in May 2021 in partnership with dacadoo, a Swiss healthtech and insurtech company will see it utilising the latter’s ‘health score’. The technology provides a real-time snapshot of a customer’s overall well-being, including physical, mental, and financial aspects. Users of HSBC’s Well+ platform and mobile app can thus be empowered to make more informed decisions on a moment-by-moment basis.

As hospitals strain at the seams, there is a higher likelihood that many people will end up managing their conditions at home, isolated from clinics and hospitals. These people still need support, and again technology is rising to the occasion. Non-profit organisation Last Mile Health uses smartphone technology to support local trusted community members to deliver health services to their neighbours, preventing, diagnosing, and treating a range of everyday medical conditions and diseases from malaria to diarrhoea. This works to overcome challenges at a local level associated with illiteracy, social exclusion, and social division, promoting social trust in healthcare delivery.

The pandemic has driven up social isolation and stress levels, causing significant psychological damage to many. To address this, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) moved quickly to repurpose an existing smartphone app called GoodSAM, originally created to provide immediate cardiac arrest support via trained first responders living in the local community. When Covid-19 hit, the NHS extended it to become a deployment app for 750,000 community volunteers, matching volunteers to nearby people in isolation who need help, whether for shopping, prescription pickups, or just a chat on the phone. This service didn’t just meet the immediate practical need. New research from the London School of Economics show that these small acts of kindness boosted volunteers’ well-being and increased their feeling of belonging within their local communities.

A bank that partners with community initiatives such as these would have a massive positive impact at ground level, especially for those in remote underserved areas; another genuine way of enhancing financial inclusion.

Unemployment is the second largest disruptor to financial well-being and the pandemic has taken its toll, causing a loss of 81 million jobs in the Asia-Pacific region in 2020. Hope is available in new AI-driven solutions that help jobseekers to get employed. One example of this is ‘Bob’, a digital job coach. Winner of the UK’s Nesta CareerTech Challenge Prize 2021, Bob analyses information about jobseekers’ needs and the challenges they face. Bob then helps jobseekers to understand how their skills and job application techniques fit with employers’ requirements. Jobseekers receive ongoing digital coaching and motivation via email, text, and a personalised app. In trials, 50% of jobseekers reported that Bob’s coaching was a key factor in finding a job.

For banks, investing in employment initiatives is beneficial to increasing income stability, preventing defaults, or discovering new talents for its own hiring needs. A digital solution like Bob would be easily scalable to meet demand. Barclays’ LifeSkills programme is in its ninth year of operation, and provides online and app-based training, courses, workshops, and other interventions to drive up employability for people with low literacy, those who have been off work from illness, and women coming into employment from the criminal justice system, to name a few of their target segments. By 2020, 11.7 million learners had participated in LifeSkills since the launch of the programme.

Earning potential refers to the factors that contribute to someone’s ability to earn a higher income. This is often related to their level of post-secondary education. The pandemic has pushed higher education establishments to go digital much quicker, in the face of cancelled in-person courses. There is already a revolutionary move towards rapid development of massively open online courses (MOOCs). MOOCs are purely digital, online, and career focused. They use AI to automatically grade assignments, which massively reduces faculty labour and pushes down costs. These digital platforms can scale up to thousands of students, thus democratising higher education. Courses are broken down into transferrable micro credits, which make gaining certifications more accessible and flexible.

If banks can get behind this and provide access to affordable and accessible higher education for all, aside to the obvious CSR benefits, this could push up their customers’ and employees’ earning potential, an obvious plus to banks in the long term. Santander is already on board with this cause, investing EUR106 million in 2021 through partnerships with nearly 1,000 universities and institutions across 15 countries.

These are exciting and inspiring possibilities, but before jumping in with both feet, we pause a moment to consider the downsides. Any use of artificial intelligence requires strong privacy policies, data ethics guidelines, and governance processes to be in place. Digital initiatives that store and analyse identifiable customer or employee data should seek explicit consent from each customer or employee from the outset. This may be tricky to obtain depending on the context. Would you as an employee agree to allow your employer to screen your Microsoft Teams meetings to spot signs of mental illness in your conversations? Unlikely.

It’s also important to note that whilst many of the positive solutions above are delivered on mobile devices, we are still in the early days of understanding the negative impact of these devices in our lives. There are concerns that these very same mobile devices can be responsible for problems with mental health and impaired well-being, for example the excessive use of social media leading to poor mental health. We need to understand how best to minimise potential harm and maximise benefits for any apps we choose to explore.

In these challenging times, it’s easy to despair. Instead, let’s keep supporting, exploring, pushing, and trying. Through our actions, we inspire others to do the same.

Dr Amanda Salter is Associate Director at Akasaa, a boutique content development firm. Based in Newbury, UK, she has delivered award-winning global customer experience (CX) strategies and been a practitioner of Agile for over a decade. Her recent guest lecture at the University of Cambridge shared insights on architecting impactful CX. Dr Salter holds a PhD in Human Centred Web Design; BSc (Hons) Computing Science, First Class; and is a certified member of the UK Market Research Society and Association for Qualitative Research.