Fake News: Can You Handle It?

Wrestling a US$78 billion problem.

By Kannan Agarwal

Whilst the phrase ‘fake news’ has been bandied about since the late 19th century and was primarily used by news outlets to attack their rival, it was during former US President Donald Trump’s tenure in office that its use entered mainstream lexicon; the term consistently trended on Google search from 2017 as one of the top searches and new organisations and alliances have been set up, such as the European Commission’s (EC) High-level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation, to counter the rise of mis/disinformation through digital channels.

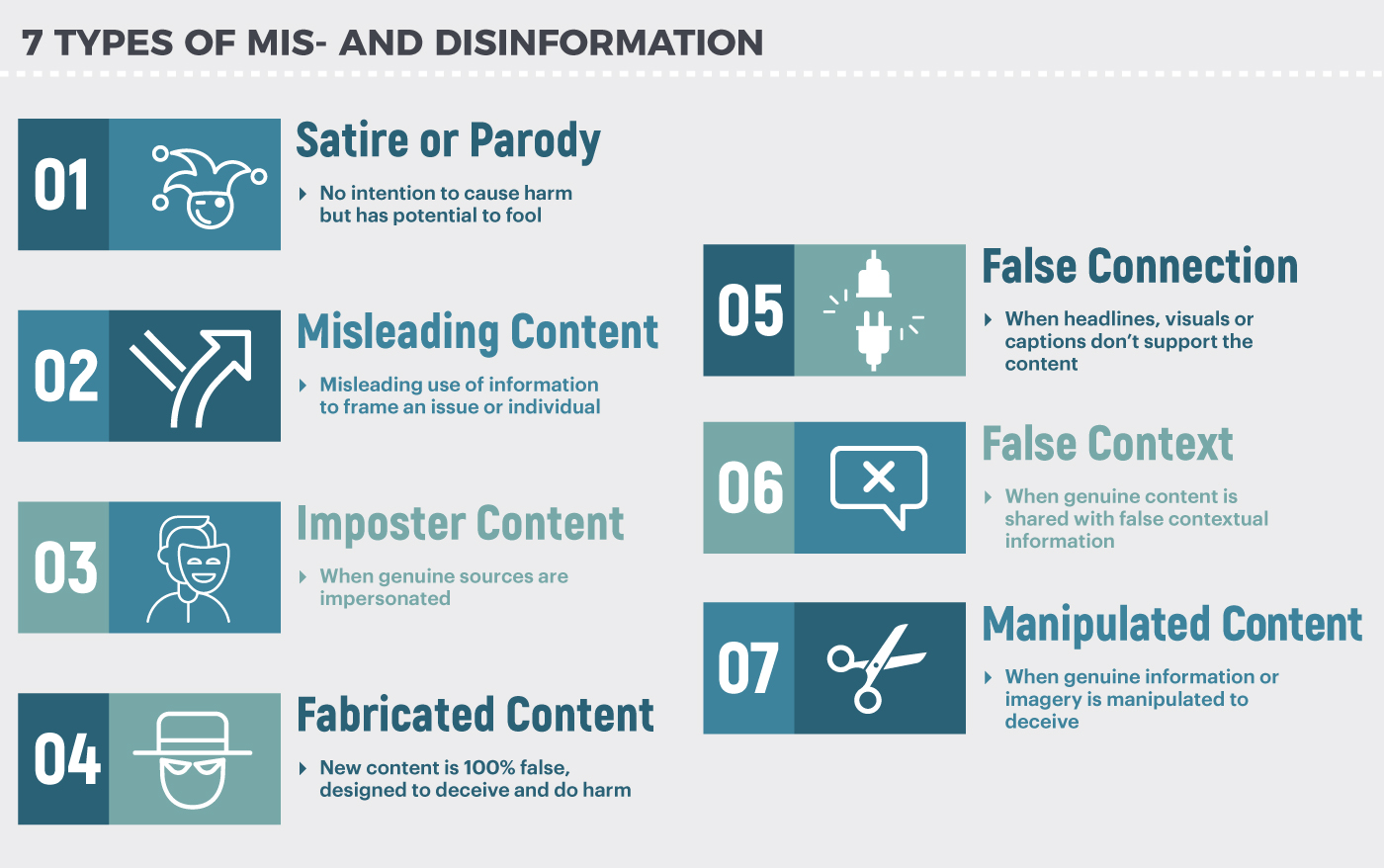

Fake news are stories which contain no or just some verifiable facts, sources, or quotes. They could be propaganda (motivated to mislead readers) or designed as ‘clickbait’ (to generate clicks for economic profit). Author Claire Wardle together with Global Voices, a multilingual online platform for digital activists, have visualised the seven types of mis/disinformation campaigns (Figure 1) for readers to understand the landscape of fake news campaigns.

There are two kinds of fake news: those that are so preposterous you immediately know it’s fake; and those that contain ‘truthiness’, the quality of seeming to be true and could, in fact, contain some factual elements to make it believable, but are overall inaccurate. The second category inflicts greater harm on society and the economy.

One of the most comprehensive studies on the subject was conducted by economist Roberto Cavazos of the University of Baltimore. Commissioned in 2019 by CHEQ, an artificial intelligence (AI) and cybersecurity solution company, Cavazos’ report, The Economic Cost of Bad Actors on the Internet, although using pre-Covid figures, remains one of the most in-depth global analysis of the economic impact of internet harm. The report measures the price paid by businesses and society across the range of online crimes, including ‘pump and dump’ schemes (where the price of a stock is boosted through false, exaggerated, or misleading positive statements), news of spoof trading (when a trader places a bid or offer with the intent to cancel before execution, thereby creating an untrue picture of actual demand for or supply of the security), and other sorts of financial disinformation or misinformation.

The report puts the total global economic loss at USD78 billion annually, which includes:

However, these are merely the direct financial costs – losses and opportunity costs imposed on society – that are being accounted for. According to Cavazos, indirect costs such as impact on the quality of life, increase in fear, changed behaviour, are less tangible but must also be priced in.

“Fake news is further diminishing public trust in specific sectors — trust in the news media has dropped from 55% in 2015 to 32% in 2019. Trust in peer reviews has dropped (online reviews were found in the UK alone to influence USD26 billion a year of consumer spending each year). For instance, Tripadvisor claims 0.6% of its 66 million annual reviews are fake. In 2018, 34,643 businesses out of the 8+ million locations listed on TripAdvisor received at least one ‘ranking penalty’ for encouraging or paying for the submitting of fake reviews.”

“Other indirect costs include the effects of constant vigilance, energy and resources to defend against and repair damages caused by campaigns of misinformation. This effort is often diverted away from innovation, training, corporate social responsibility and many other vital economic sources of growth. These positive economic benefits, necessary for competition and growth, are casualties in the war against fake news.”

Although it is of global concern, very few solutions have been proffered on how corporations and brand owners can counter online dis/misinformation campaigns.

Organisations such as the European Commission’s High-level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation have remained just that – high level. Their report, A Multi-dimensional Approach to Disinformation, is of little practical use to brands and businesses that need solutions and tools that work, now.

Think tanks are generally concerned with policy and legislation. Their recommendations focus on strengthening government oversight without infringing on freedom of expression, the role of news media outlets, and public responsibility to fact-check for responsible news sharing. What proactive measures can corporations take to protect themselves?

One of the most practical advice comes from public relations (PR) practitioner Kathleen Stansberry, an assistant professor of media analytics and strategic communication at Elon University. Specifically, her article, The Financial Drain of Misinformation, developed for the PR Society of America’s Voices4Everyone initiative, advocates that organisations stop funding fake news by utilising the range of technological tools at hand.

For example, she cites JPMorgan Chase’s policy of limiting online ad placements to only pre-approved websites, also known as ‘whitelisting’ or ‘safe listing’. Another solution is for companies to invest in social listening, the process of observing and analysing digital conversations for red flags, and predict trending issues that could impact the brand.

It is important to note that although it is common for financial institutions to already have crisis communication teams who actively monitor social media, social listening involves predictive analysis and helps companies identify risks before they spiral out of control.

Financial markets have been dealing with fake news and hoaxes ever since money changed hands, but it was easier to detect crime in an analogue world. Today, digitalisation has expanded the surface of attack to include platforms and channels that are decentralised and at times, encrypted. Take, for instance, the forwarded WhatsApp message that sparked a run on the UK’s Metro Bank in 2019 or similar online speculation in 2020 that saw at least five bank runs against small China lenders such as the Bank of Hengshui. Sent electronically, and sometimes using encrypted platforms, it is often difficult to trace the source of fake news.

“With technolog[ical] advances, and despite rapid efforts at detection,” warns Cavazos, “the risks and costs of fake news will only grow. Fake-news-generated black swans may have the power to destroy iconic firms and generate untold economy-wide chaos and harm.”

This bleak outlook means that banks must shore up their first line of defence, defined by the Bank for International Settlements as management and internal control functions which own and manage the banks’ risks. In this instance, it means risk personnel in charge of digital detection tools, such as social listening and hoax-spotting algorithms, working together with the communications team. Vigilance is, in itself, a deterrent against hoaxers and hackers.

Kannan Agarwal is a content analyst and writer at Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm.