Moral Reasoning: How Do We Get to the Right Decisions?

Understanding how individuals are influenced and what drives their actions (or inactions) hold immense importance for us in banking.

Understanding how individuals are influenced and what drives their actions (or inactions) hold immense importance for us in banking.

By Bob Souster

An overwhelming majority of bankers want to do what is right, for their employers, for the community, for society as a whole and for themselves. An industry that has been built on the trust and confidence of others has to take this as a given. But while we hope to take decisions and actions that reflect goodness, how do we arrive at our decisions about right and wrong? This article considers moral reasoning. It examines some of the factors that influence the thinking of individuals about their decisions. It is not about whether a decision is right or wrong, but the process through which the decision is taken.

The simplest view of moral reasoning is that there is no reasoning involved at all and that, as human beings, we intuitively know whether something is right or wrong. There may be multiple influences such as parents, friends, teachers, social environment, religion and countless other factors. These have been examined exhaustively by sociologists, many of which write of socialisation, and by psychologists, who are concerned with how the mind works and its impact on behaviour.

Enlightenment writers such as David Hume believed that concepts of morality were based on the perceptions of individuals and were akin to emotions. Three hundred years later, Jonathan Haidt supported Hume’s simple view by writing of ‘moral intuitions’. Yet, even in Hume’s time, not all authorities agreed that morality relied on instinct. Immanuel Kant, for example, believed that there were universal laws that should always apply, and that these ‘maxims’ should form the basis of duties or obligations to others.

There is no conclusive evidence as to whether our decisions are driven by instinct or logical processes. Many bankers find themselves in situations in which they have to make snap judgments reflecting what they genuinely believe to be right. Is this through a finely-tuned sense of justice instilled through knowledge and judgment built from experience, or do their minds subconsciously follow a process?

Theories of cognitive moral development considered moral reasoning as a process. Most of the theories relating to this approach were formulated by carrying out empirical research, such as by asking people questions and assessing their responses. Jean Piaget studied how cognitive processes developed from childhood to adulthood. He believed that children were mainly influenced by rules made by influential people in their lives, or even by God. These rules were rigid and would often create notions of causation, such as ‘naughty behaviour will result in punishment’. In this way, Piaget fused the duties (which arise from rules) with consequences of breaking the rules. Piaget believed that as the individual matured they would enter the autonomous phase, when it would be important to consider the underlying intentions of an individual, an acceptance that different people may have their own interpretations of morality and in some cases rules should be broken if appropriate to do so.

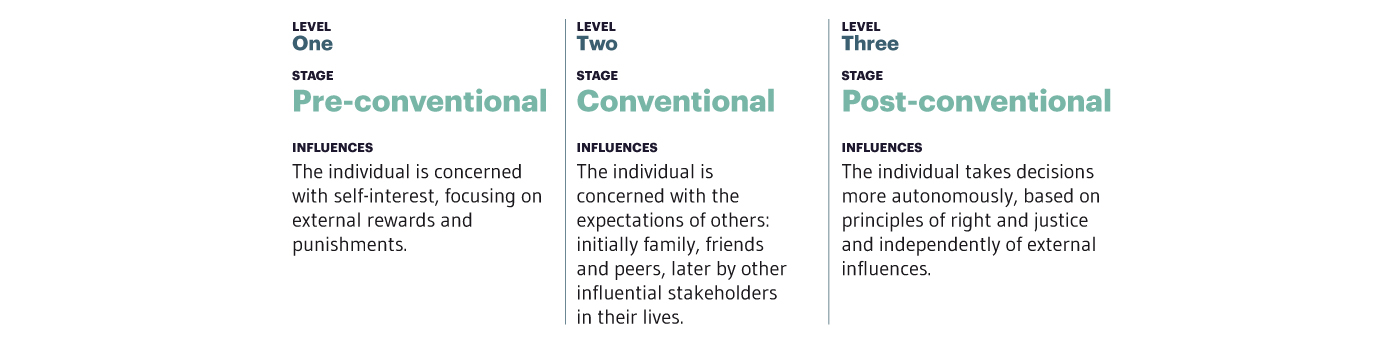

Piaget’s theory paved the way for research by Lawrence Kohlberg, who developed his theory of moral development by posing ethical dilemmas to children of various ages and examining their responses. He concluded that individuals would apply different reasoning processes as they matured through three generic stages (Figure 1).

Kohlberg’s theory posits that individuals move through these stages sequentially but at any given time may make judgments and take decisions based on any of the three stages.

During the deregulation of the 1980s, when banks were growing rapidly and becoming more sales-driven enabled by a ‘soft touch’ regulatory environment, it was possible for an able and ambitious person to make a name for themselves by meeting and exceeding their targets, just as less precocious contemporaries might have been more fearful of the negative consequences of failing to perform. In both cases they exhibit pre-conventional characteristics, being driven by perceived rewards and punishments respectively. Over two decades later and in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2009–2011, bankers were more likely to consider the expectations of others, notably government, regulators and their employers, as banks adopted more conservative, risk averse policies and the demands of regulators changed radically. This reflects conventional reasoning. However, one problem with generic theories is that, by definition, they do not apply to all people or situations. For example, it might be argued that whistleblowers who risked (and in some cases sacrificed) their careers on matters of principle took the high ground by considering right and justice above all, clearly demonstrating post-conventional reasoning.

Kohlberg’s theory is not without critics, who have pointed out that his research base was narrow (all male subjects, small control groups, all in the USA). Carol Gilligan, a contemporary of Kohlberg, developed a parallel theory which postulated that women adopt different reasoning to men and are more inclined towards an ‘ethics of care’.

Drawing on the work of classical Greek philosophers and Enlightenment writers, as well as more contemporary research such as that of Kohlberg, Roger Steare developed an integrated and data-led approach to how individuals arrive at ethical decisions. His early findings were based on bringing together three approaches to ethics: virtues; duties; consequences. Steare’s three typologies are described in Figure 2.

Steare’s theory is a powerful attempt to bring together several theories of ethics. It is also built on practical research, as he built his data from inputs collected from thousands of online questionnaires.

We will never arrive at a definitive answer to the question, “How do we arrive at ethical decisions?“. The theories and concepts discussed briefly in this article offer clues and indicators of how individuals are influenced and the factors that drive their decisions and actions, and sometimes their inactions. However, the discussion has important implications for us in the world of banking. When we assess new recruits, when we seek to influence the culture of our organisation and promote exemplary practices, when we try to promote noble behaviours and deter malevolent behaviours, we need to understand the multiplicity of factors both within and outside our control.

Robert (Bob) Souster is a Partner in Spruce Lodge Training, a consultancy firm based in Northampton, England. He lectures on economics, corporate and business law, management, corporate governance and ethics. He is the Module Director for ‘Professional Ethics and Regulation’, a core module of the Chartered Banker MBA programme at Bangor University, Wales.