So, How Much Do You Make?

The debate on pay transparency continues.

By Majorie Giles

Pay transparency is a policy in which corporations or employers furnish pay-related data to employees. This is increasingly being adopted – through legislation or voluntarily – as a means of tackling discriminatory pay practices by bringing down the barriers of secrecy and is considered by some as a tangible tool towards greater diversity and inclusion in corporations, especially for women in science and technology.

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals also advocates this as part of Goal 8.5, which aims “by 2030, to achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value”.

It’s important to note that each jurisdiction has had to find its own path, navigating the uniqueness of each ecosystem, and that the road to transparency can take many forms:

> In the US, 17 states currently have laws around pay transparency that allow employees to discuss their pay without fear of recrimination, but not all of these states require employers to provide salary ranges to job candidates. Some corporations voluntarily use pay-gap reporting as a strategy to prevent possible litigation, although some tech giants have recently been sued for alleged discriminatory pay practices when they did not sufficiently address pay disparities; these cases are still pending in the courts.

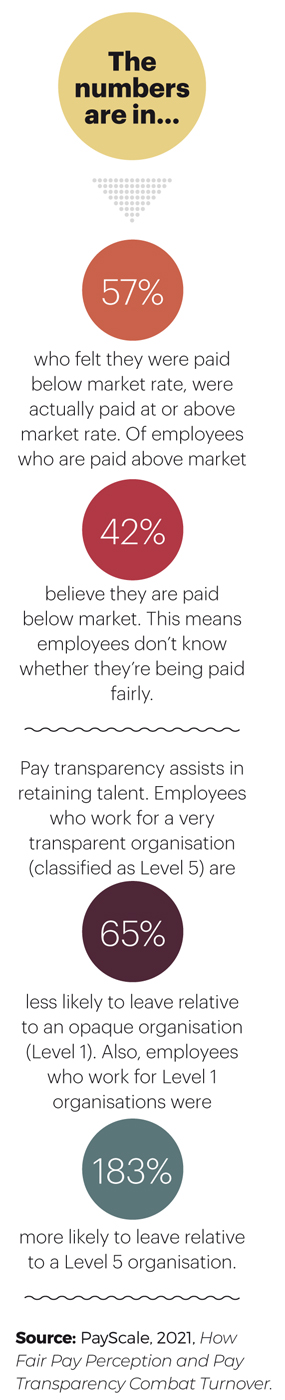

When it comes to talent management, studies have shown that opaque pay policies lead to higher turnover, with some employees more likely to leave within six months; whilst pay transparency increased employees’ perception of fairness, trust, job satisfaction, and boosted individual performance. But it is far from a bed of roses.

There are nuances in the pay transparency debate which are rarely highlighted. Multiple studies confirm that making salaries transparent will result in a drop in average compensation for employees across the board. In one instance, when the California state government published their city managers’ pay scale back in 2010, average remuneration declined by 7% in 2012. Although transparency induces direct supervisors to streamline remuneration gaps quickly, the downside is that the same supervisors will be inundated with disputes by disgruntled staff and likely be solicited for non-financial rewards to offset the pay compression.

In The Unintended Consequences of Pay Transparency, published in the August 2022 issue of Harvard Business Review, authors Leon Lam, Bonnie Hayden Cheng, Peter Bamberger, and Man-Nok Wang state that the abovementioned dilemma can be avoided early on if corporates design their pay transparency programmes with three things in mind:

+ Make the performance-reward link clear and objective.

Companies will not reap the benefits of a transparent pay process if it lacks an objective performance measurement or reward system. Combining performance metrics that clearly link performance with rewards – for example, objectives, and key results – with continuous monitoring allows employees to better understand how their work relates to specific outcomes. This takes some of the pressure off managers to judge, often subjectively, individual employees’ performance during appraisal periods, which is particularly relevant in jobs where performance is not easily quantified.

+ Provide training to facilitate pay-related communication.

One challenge in adopting pay transparency is the managers’ limited understanding of their company’s compensation policy, even though they are the ones managing employee inquiries. As a result, they fall short of adequately communicating the underlying processes of the compensation system. Connected to this is a lack of appropriate channels for employees to voice their feelings about transparency policy initiatives and a lack of resources for them to understand the pay system in the first place. Without proper manager training and learning resources for employees, a transparent compensation system will only lead to further confusion.

+ Restructure reward systems.

As the authors’ research reveals that pay transparency fuels more non-monetary ideal requests, companies should consider formalising idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) into their reward structures, such as offering developmental i-deals to upskill employees and task or location i-deals to reward and retain loyal employees. When requests are not limited to an individual privilege or a hidden arrangement, the risk of unfairness can be mitigated.

During the 2018 proxy season, impact-investing firm Arjuna Capital filed shareholder resolutions, calling on nine US-based financial institutions – Citibank, JP Morgan, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, Amex, Mastercard, Reinsurance Group, Progressive Insurance – for detailed reports on the percentage pay gap between male and female employees across race and ethnicity, including base, bonus and equity compensation, policies to address that gap, the methodology used, and quantitative reduction targets. Two years earlier, Arjuna had successfully led proxy action against seven tech companies, including Adobe, Apple, and eBay to disclose their gender pay gaps.

In a surprising move, Citigroup stepped up and became the first bank in the world to voluntarily disclose its median gender pay gap and adjusted pay results ahead of the shareholder vote. The activist investment firm lauded the move and immediately withdrew its resolution.

In a January 2018 memo to its employees, Citigroup stated that on an adjusted basis, its female and minority employees faced a pay gap of only 1% compared to male and non-minorities in the corporation. Several months later, it further disclosed that on an unadjusted pay basis, women and minorities at the banking group earned 29% less than men and non-minorities. Reactions were mixed. Some publicly panned the banking giant for the salary disparity, others lauded the group for its candour.

The bank took steps to raise the wages of female employees and set diversity targets within the corporation. It also championed pay equity in business through collaborations such as The Female Quotient, a thought leadership platform for women, to develop a free digital tool that provides companies with a snapshot of their raw pay gap for insights into what concrete measures should be taken to increase diversity efforts.

Since then, Citigroup’s ‘raw’ gender pay gap has slowly reduced, although it seems to have been sitting at 26% over the last two years. Globally, the share of women in roles from assistant vice president to managing director increased to 40.6% from 37% and the share of African American employees has also increased to 8.1% from 6%. Today, diversity goals are explicit targets on the scorecards used to assess managers’ performance and the company is continuing to refine these metrics, including the implementation of a post-pandemic remote-work option that has helped to recruit and retain diverse talent.

The bank’s 2022 memo states: “When we started on this journey in 2018, we were candid about our talent representation gaps among Black and women colleagues across the firm and we did something about it.” The actual results are far from groundbreaking, but its moves have paved the way for other financial institutions to step up.

In the Asia Pacific, the momentum is fastest in Australia. According to the country’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), the national pay gap is at 13.8% and the financial services sector leads with one of the largest gender pay gaps according to industry, reinforced by policies that enforce wage secrecy in employment contracts.

In March this year, Westpac was the country’s first major bank to scrap age-old pay secrecy clauses in its contracts, allowing 40,000 employees to talk freely about how much they get paid without fear of recrimination. Its spokesperson said that the bank hoped the policy would contribute to broadening pay equity initiatives as it believed that “having open and transparent conversations and measuring that is what changes things.” In less than 30 days, Commonwealth Bank Australia and other Australian banks followed suit.

This is just the beginning of reforms for pay transparency.

The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) latest guidance, Pay Transparency Legislation: Implications for Employers’ and Workers’ Organizations, indicates that gender-responsive policies are coming back to the fore after several years of stalled progress due to Covid-19.

In its survey of employers’ and workers’ organisations in countries with pay transparency legislation, the ILO states that whilst there were pros and cons, the body of evidence tilts in favour of the former, which has net positive effects for the economy.

Current practices on pay transparency legislation can entail:

Almost all companies in Asia view this discussion with trepidation. As if to illustrate this point, whilst researching for this piece, I came across an online article on a leading news portal which touted “honest views” by CEOs on the Malaysian pay gap. Clicking on it led to…nowhere. A dead link.

Will this be the last we hear of it?

Australia’s latest pay transparency policies and strategies require that employers with 500 or more employees must meet a set minimum standard to demonstrate their commitment to gender equality. Specifically, large employers are required to have a formal policy or strategy in at least one of the following areas:

The WGEA website offers resources on how to satisfy the reporting obligations, such as a salary calculator, reporting questionnaire, workplace profile, and so on. The agency also provides each relevant employer with a competitor analysis benchmark report on their gender equality performance, allowing the employer to realise which areas related to gender equality could be improved upon in their enterprise. The strength of Australia’s pay transparency system is in the comparison of analysis benchmark reports, a mechanism to allow employers to compare their gender report to that of other enterprises in the same or similar industries, and other enterprises of the same or similar size.

According to information available through the WGEA, comparison of analysis benchmark reports encourages enterprises to act and address the results of their own analyses. In 2018, more than half of the enterprises that conducted a pay gap analysis and detected a pay gap reported their findings to the executive and board levels. Improved gender pay outcomes are far stronger for companies that combine specific pay equity actions, reinforcing the effectiveness of those actions with accountability through reporting to company executives and the board.

Marjorie Giles writes for Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm, and holds a Masters in Clinical Psychology.