Taking The First Step with Nature: The Next Risk Frontier

Imminent threats of the nature crisis demand swift and decisive action.

Imminent threats of the nature crisis demand swift and decisive action.

By Divyaasiny R Rajaghantham and Wan Noorfatin binti Wan Mohd Zani

The past decade has witnessed an unprecedented decline in nature. Nature loss is also inextricably interlinked with climate change, and achieving global goals for addressing one cannot be in isolation from the other. With half of the world’s total gross domestic product, approximately USD44 trillion, being moderately or highly dependent on nature, nature loss has far-reaching consequences not just for the ecology, but also for the economy.

While the climate debate has synthesised around the Paris Agreement’s ambitions to keep global warming below 1.5°C, there has been no equivalent target to spur nature action until now. Last year, representatives from 196 countries, including Malaysia, convened in Montreal, Canada, for a global summit that ended with a landmark biodiversity agreement, known as the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. The significance of this landmark deal lies in the fact that countries can now refer to the GBF’s overarching goals and targets as their ‘North Star’ to guide biodiversity agendas at both national and sectoral levels.

The World Economic Forum has flagged biodiversity loss as a critical threat over the next decade, making it clear that addressing nature loss is an urgent priority. According to the Global Forest Watch annual forest analysis, our planet lost 3.75 million hectares of tropical primary forest in 2021, equivalent to the size of one football pitch, every six seconds. Given Malaysia’s status as one of the world’s megadiverse tropical countries, the country’s rapid economic development has heavily relied on its abundant natural resources. As a result, we inherently face high economic exposure to nature-related risks, which makes us vulnerable to changes in biodiversity and its related ecosystem services.

Fundamental to managing nature-related risks is understanding how the financial sector is exposed to them. According to the Network for Greening the Financial System, nature-related risks arise from the impact-dependency relationship between an organisation with nature, which may affect the economic performance of the organisation and subsequently pose financial risks to the financial institutions that are financing, investing, or underwriting them.

Similar to climate-related risks, nature-related risks consist of physical and transition risks. Physical risks are a direct result of an organisation’s dependence on biodiversity and ecosystem services, which are typically categorised as provisioning (e.g. timber, food production), regulating (e.g. water regulation, carbon sequestration), and cultural (e.g. ecotourism). The degradation of these services can give rise to physical risks and disrupt the business continuity of their financing counterparts, which can lead to operational disruptions and weaker profitability, thus impacting debt repayments. An example of nature-related physical risk is the unplanned land conversion for agriculture in the Amazon rainforest. A study has shown that the removal of native vegetation in the region to make way for soy and beef sectors can potentially engender erratic rainfall patterns and increase droughts that could result in a sharp decline in crop yields, eventually affecting financial institutions that are heavily invested in the agricultural sector in Brazil.

On the contrary, nature-related transition risks emerge due to the misalignment between an organisation’s activities and the changing landscape in which it operates. Organisations with strong negative impacts on nature will be most vulnerable to these risks (e.g. agriculture, forestry, fishery, mining, energy, transport, and infrastructure). Abrupt transitions, in the form of technological breakthroughs, regulatory changes, and shifts in consumer preferences can all give rise to market, reputational and regulatory risks, which can, in turn, increase the probability of defaults on loans and write downs of investments in affected companies. The most recent endorsement of the European Union Deforestation Law, which will prohibit the import of deforestation-linked products, will most likely be a source of regulatory driven transition risk for financial institutions that have exposure to deforestation and conversion.

Nature-related risks do not only affect individual financial institutions, but can also pose significant macroeconomic and financial implications to the system as a whole. Recognising this, central banks and financial supervisors in several countries such as the Netherlands, France, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa – and even Malaysia – have conducted exploratory studies to understand the exposure of the financial sector to biodiversity-related risks. Key findings from a joint report by Bank Negara Malaysia and World Bank revealed that the country’s financial system is exposed to a broad range of nature-related physical and transition risks – 54% of the commercial loans portfolio analysed were exposed to sectors that highly depend on ecosystem services and about 87% were exposed to industries that strongly impact nature.

At the ground level, rapid and scaled-up corporate action is critical to halt and reverse nature loss, and Target 15 of the GBF exemplifies this. The target calls for financial institutions and large companies to regularly monitor, assess, and transparently disclose nature-related risks, dependencies, and impacts along their operations, value chains, and portfolios, to reduce negative impacts on biodiversity and increase positive impacts. Implementation of this target will raise the accountability of the private sector in addressing their impact on nature and encourage them to be more transparent and adopt sustainable production practices.

However, it is to be noted that assessing nature risks is no easy feat. In contrast to climate change, biodiversity is a more complex and multidimensional paradigm to understand – it cannot be simplified within a single metric for comparison, unlike carbon reduction, which can be measured in tonnes of CO2. To further add to the complexity, nature-related risks are also highly spatial-specific and require asset-level location data for the assessment. Unsurprisingly, investors are still grappling to understand what this means in implementation and many simply do not know where to start.

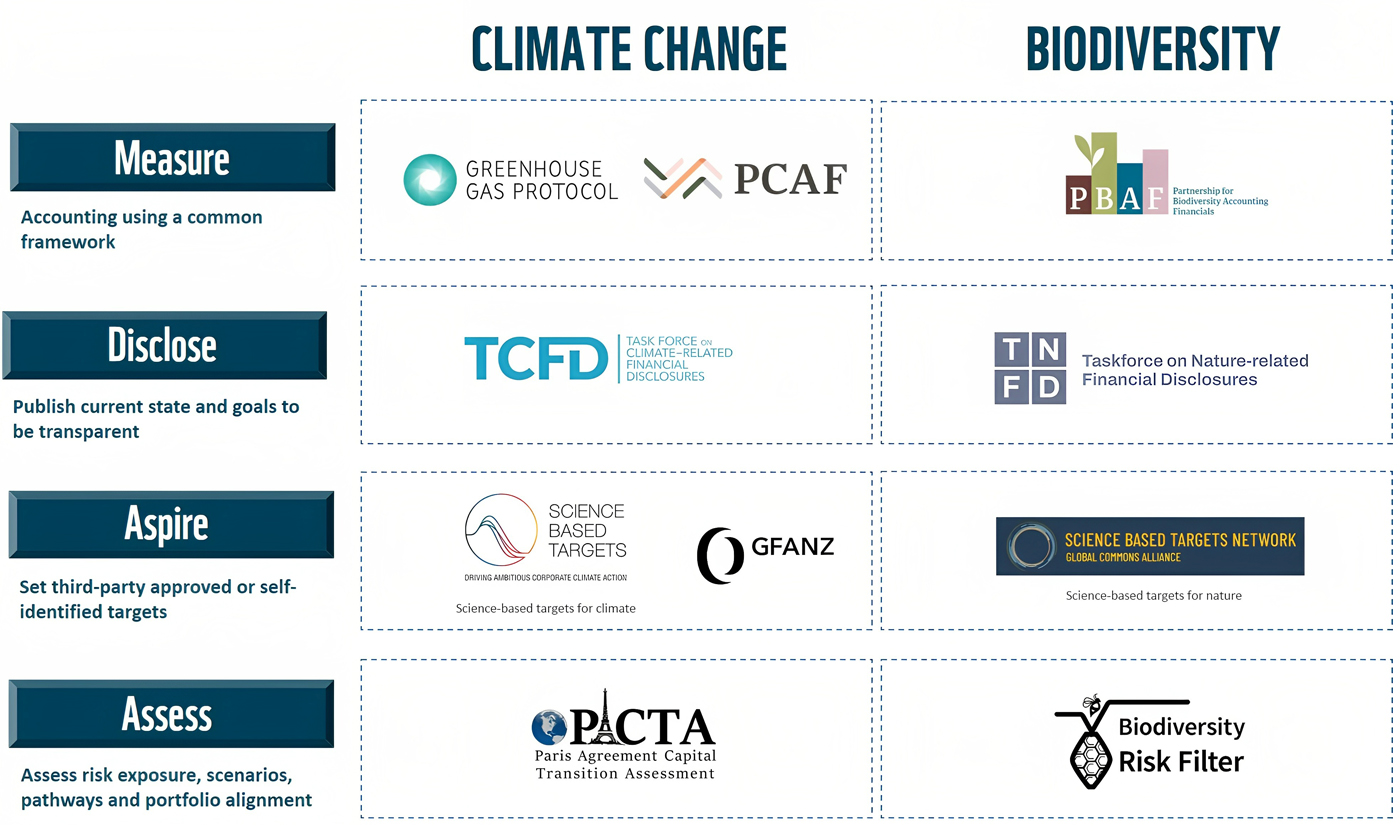

Fortunately, in recent years, there has been an emerging body of frameworks, standards, tools, and methodologies for the private sector to account for, assess, disclose, and manage their nature-related risks (see Figure 1). Many of these initiatives tend to mirror their climate counterparts and are gaining stronger momentum. These include the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures framework (to guide nature-related disclosures), Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) (to guide target setting for nature), and Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials (to guide the measurement of biodiversity impact/dependencies).

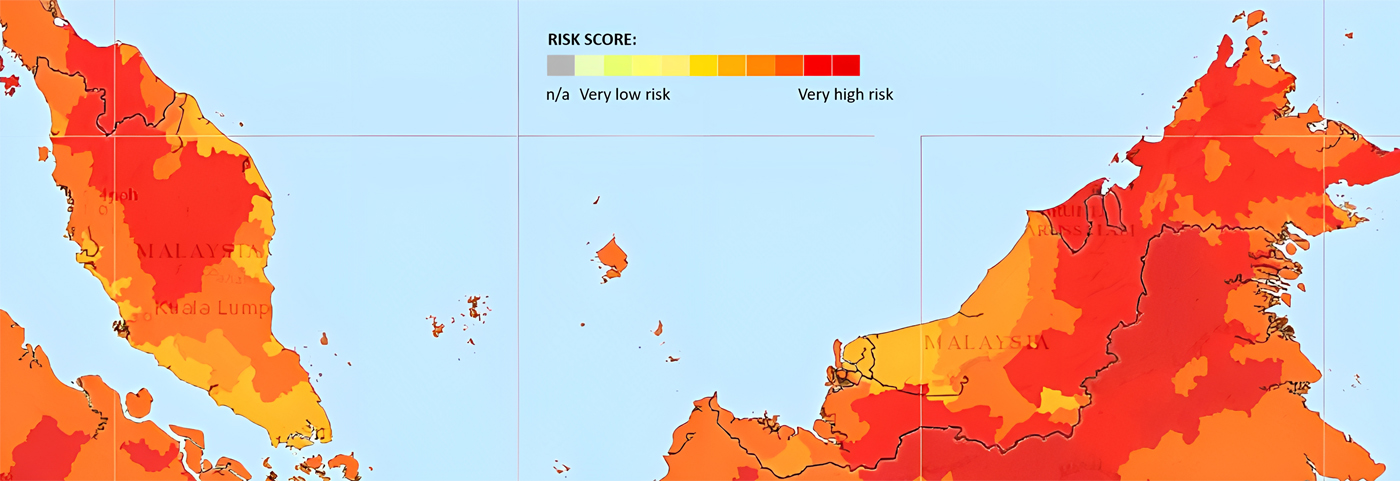

While these frameworks offer valuable guidance and a good starting point for organisations to understand, assess and respond to biodiversity-related risks, they may still seem technical and complex, potentially deterring their adoption. To help address this, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) recently launched the Biodiversity Risk Filter (BRF) tool, which breaks down the complexity of biodiversity and provides practical, decision-useful information in a visually comprehensible manner. Known to be the first of its kind, the BRF is an open-sourced, spatially explicit biodiversity assessment framework that builds on existing data and tools.

The BRF tool covers a range of risk indicators, some of which are pertinent to the Malaysian context, including landslides, key biodiversity areas, availability of flora and fauna, and water conditions. It employs a four-level risk hierarchy model to group these indicators into thematically relevant risk categories and risk types, informed by 56 risk metrics that comprise raw data and global biodiversity datasets.

The current version of the BRF tool allows organisations, including financial institutions, to conduct location-specific and industry-specific assessments of biodiversity-related physical and reputational risks across an organisation’s operations and supply chains. The tool is composed of four key modules:

By gathering asset-level location data from clients and inputting them into the BRF tool, financial institutions will be able to build an accurate picture of their biodiversity risk exposure. Insights from the tool can help investors prioritise their actions and systematically plan their mitigation measures at a portfolio level. This is important for deciding resource allocation on in-depth investigations and when engaging with companies they invest in on their impacts, dependencies, and respective mitigation strategies.

It took decades for the private sector to grapple with the complex challenges posed by climate change, finally culminating in a coordinated global response to address its risks. Although nature-related risks have received less attention and remain less understood, they cannot afford to follow the same timeline in addressing them. The imminent threats of the nature crisis demand swift and decisive action. To effectively manage the risks associated with nature loss and build resilience across their value chains, the financial sector must begin to act now, leveraging the emerging standards and frameworks being developed for nature.

Divyaasiny R Rajaghantham is a Senior Analyst and Wan Noorfatin binti Wan Mohd Zani is a Manager in the Sustainable Finance team at WWF Malaysia. Together, they provide valuable support for various sustainable finance initiatives, collaborating with regulatory authorities and financial institutions to integrate environmental, social and governance policies and practices in the financial sector.