Embedded Finance: Risks & Rewards

Can banks find the sweet spot between innovation and security?

Can banks find the sweet spot between innovation and security?

By Julia Chong

By Julia Chong

Embedded finance has emerged as a critical component in today’s financial ecosystem.

As recently as 2022, many viewed the relationship between banks and fintech (financial technology) with trepidation, with newswires bearing headlines like “Banks beware, Amazon and Walmart are cracking the code for finance”. What has come to pass, however, is a symbiotic relationship, one where embedded propositions between financial and nonfinancial institutions have created rapid and significant growth for both parties.

Consulting firm EY estimates that the global embedded finance market size is set to grow 130% from USD264 billion in 2021 to USD606 billion in 2025. The upside for fintech is that they can proffer banking products and services faster and with minimal regulatory burden; for banks proper, it translates to new revenue streams, insightful customer data, and a wider omnichannel brand footprint. Users gain satisfaction from a seamless banking experience.

One example is the Belgium real estate market where customers can search for their dream home, simulate, then submit a loan application…and voila! Johan and Jeanne are now proud owners of an Antwerp home by the canal.

This illustrates the allure of embedded finance, and how the integration of financial products and services with nonfinancial platforms or services has transformed the expectations of consumers. Examples include paying utility bills direct through your local council app or getting instant approval to purchase that latest sofa through a buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) scheme when shopping online. The idea behind embedded finance is to create a frictionless user experience, open up new revenue streams, or boost established ones for both financial and nonfinancial players.

A multitude of use cases have spawned under the vast umbrella of embedded finance, also known as ‘banking as a service’ (BaaS), which can be loosely classified into the following types of products and services:

While the opportunities are promising, the security of these financial technologies remains a paramount concern. The ability to foresee and adapt to new and emerging risks in this space will determine who wins or loses in the road ahead.

Earlier this year, the US banking regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), stated that it should be the responsibility of banks to actively manage the risks arising from their partnerships with fintech.

The comments accompany a litany of consent orders issued by another regulatory agency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, imposing heightened requirements to banks’ third-party risk management programmes via its BaaS partnerships, including:

Speaking at a talk at Vanderbilt University, the OCC’s Acting Comptroller Michael Hsu’s hardline stance was: “We will not lower our standards, create a special regime, or take an overly expansive view of banking to entice new entrants or in the hope of bringing a particular activity into the bank regulatory perimeter.”

In May 2024, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) raised concerns about the growth of cloud computing technologies using third parties – artificial intelligence, distributed ledgers, and open banking systems.

At risk is the impact on operational resilience and increased fault points that come with greater connectivity between banks and nonfinancial firms.

Although existing rules and legislature are in place to protect vulnerable consumers against potential harm, many banks do not currently have the requisite infrastructure to mitigate or monitor third-party risks in a partnership model like BaaS. The BCBS states that where necessary, it will consider whether additional standards or guidance are needed to mitigate risks and vulnerabilities.

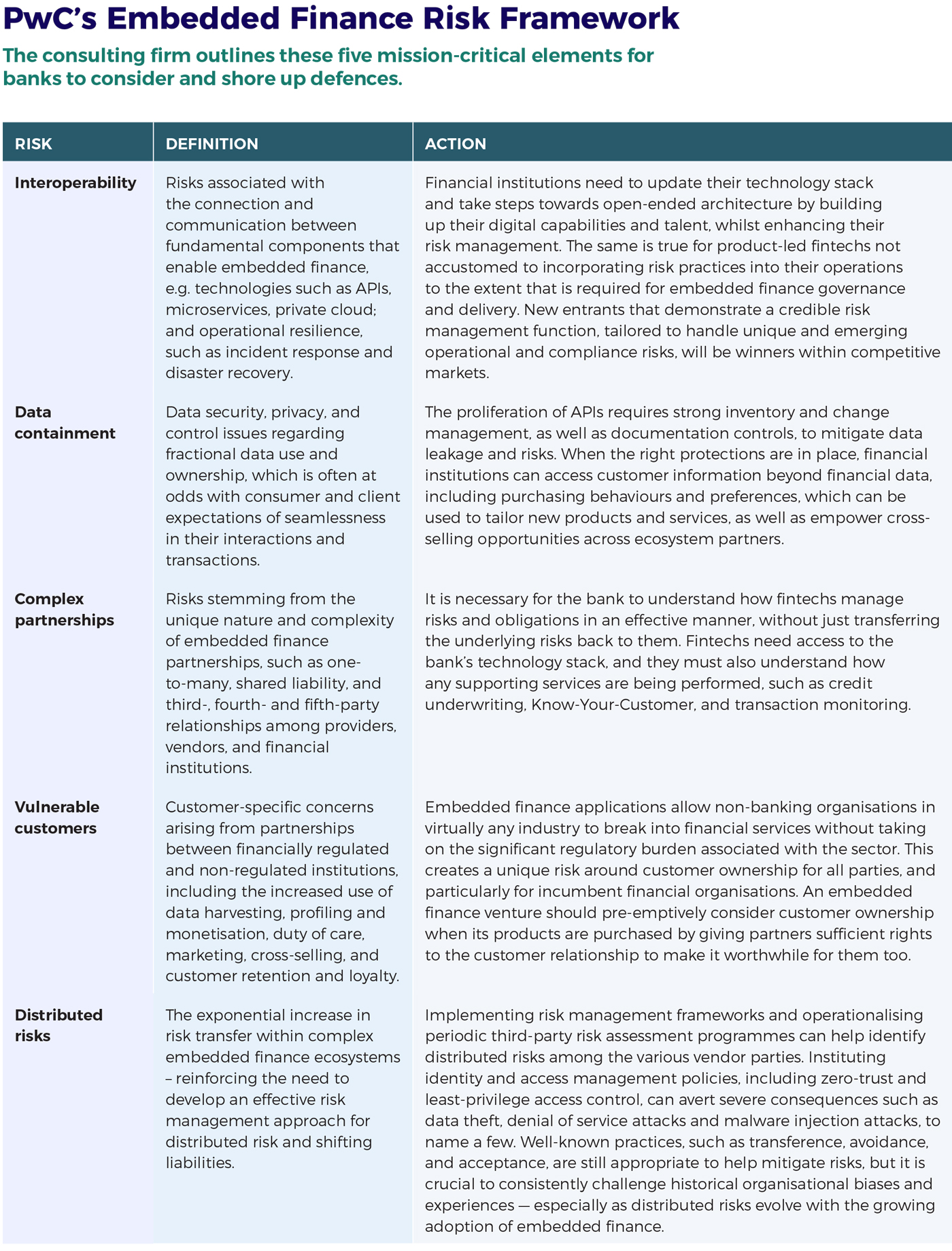

Management consulting firm PwC outlines in a May 2023 paper, Managing Risks in the Transition to Integrated Financial Services, that “as the conversation shifts away from pure risk and resilience to value preservation – and eventually to the value created through revenues from the embedded finance market – complacency is not an option.”

In other words, what seems to be a competitive edge today could easily be a knife’s edge tomorrow.

“For instance, banks that occupy a utility role within ecosystems – as a licensed partner or a liquidity provider – may be left with highly regulated and capital-intensive activities that yield little in the way of customer data and returns. Smaller banks and retailers may struggle to establish themselves in the market as consolidation becomes more widespread in the face of industry headwinds. For their part, consolidation of the largest players – including ‘too big to fail’ banks and big-tech companies – could create an insurmountable competitive advantage within ecosystems that lock customers into a handful of embedded finance providers.

“As strategic leaders tool up to operationalise embedded finance,” the firm writes, “they need to recognise and confront these broader market risks head-on if they are to compete in a shifting economic landscape.”

Although there is no hard-and-fast rule on how financial institutions can future-proof their partnerships with fintech, the Embedded Finance Risk Framework (see page 59) sets out some best practice to consider.

As banks stake their claim in this ever-changing landscape of finance, they must be mindful that the burden of regulatory compliance in every embedded finance collaboration falls squarely on their shoulders. At the first hint of a misdemeanour, prudential authorities will make them their first port of call.

Julia Chong is a content analyst and writer at Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm.