Unified Ledger: Blueprint for a Future Monetary System

The foundation of trust provided by central bank money heralds fundamental changes in the financial world.

The foundation of trust provided by central bank money heralds fundamental changes in the financial world.

By Kannan Agarwal

By Kannan Agarwal

On 20 June 2023, in a special chapter published as part of the Bank of International Settlements’ (BIS) annual economic report, the international institution for central banks discussed how it seeks to turn the page on the faltering progress of ongoing tokenisation projects through “a new type of financial market infrastructure – a unified ledger – [which] could capture the full benefits of tokenisation by combining central bank money, tokenised deposits, and tokenised assets on a programmable platform.”

Entitled Blueprint for the Future Monetary System: Improving the Old, Enabling the New, it writes: “Today, the monetary system stands at the cusp of another major leap. Following dematerialisation and digitalisation, the key development is tokenisation – the process of representing claims digitally on a programmable platform. This can be seen as the next logical step in digital recordkeeping and asset transfer.”

In finance, the issuance of tokens is used to represent assets such as central bank money or central bank digital currencies (CBDCs); bonds; equities; real estate; contracts; or even intellectual property (through non-fungible tokens). A recent podcast with Hyun Song Shin, economic adviser and head of research at the BIS, explains how tokens can be put to practical use in the financial world.

“Tokenisation is…a form of digital representation but on a programmable platform, which means that the token can govern the rules and logic regarding transfers as well as the information regarding the asset itself, like what it is, who owns it, et cetera.”

In its present form, Hyun explains that transactions are recorded on separate databases and these need to be connected through separate third-party messaging systems. This necessitates separate reconciliation processes in order for clearing to occur and transactions to be settled with finality. What the BIS envisions in the not-too-distant future is that financial institutions will harness the power of programmability of these tokens in order to combine the different parts of the process – trading, reconciliation, and settlement – into one seamless operation. For this to happen, however, the right elements must coalesce into a form that’s bigger than the current sum of its parts.

Enter the concept of the unified ledger.

The BIS report states: “A unified ledger transforms the way that intermediaries interact to serve end users. Through programmability and the platform’s ability to bundle transactions (composability), a unified ledger allows sequences of financial transactions to be automated and seamlessly integrated. This reduces the need for manual interventions and reconciliations that arise from the traditional separation of messaging, clearing and settlement, thereby eliminating delays and uncertainty. The ledger also supports simultaneous and instantaneous settlement, reducing settlement times and credit risks. Settlement in central bank money ensures the singleness of money and payment finality.

“Moreover, by having ‘everything in one place’, a unified ledger provides a setting in which a broader array of contingent actions can be automatically executed to overcome information and incentive problems. In this way, tokenisation could expand the universe of possible contracting outcomes.”

According to the report, the first instances of the unified ledger concept are likely to be application-specific in scope. For instance, one ledger could aim at improving securities settlement, whilst another could facilitate trade finance in supply chains, however, all transactions would rely on similar elements: the use of CBDCs to give some finality in terms of settlement; and the inclusion of only the relevant intermediaries and assets to ensure data privacy. The scope of a ledger will determine the players that must be involved in the governance arrangements.

Hyun explains further about the mechanics of this latest endeavour by the global financial overseer. “When we say unified ledger, we don’t mean a single ledger; what we mean is a ledger that binds different elements. The unified ledger will knit together all the different elements and only those elements. So, if you’re interested in securities transactions, what you would need is a CBDC for settlement, tokenised deposits to allow people to pay and receive, and tokenised versions of the securities themselves.

“Tokenisation has been explored in some private sector initiatives, but they are limited by the fact that it is pursued by a private institution or a consortium. It doesn’t actually involve central bank money and if you don’t have central bank money, you cannot have the final settlement that will give you the settlement finality to that transaction.

“The beauty of the unified ledger is that you’ve got central bank money in tokenised form – an example is a CBDC – which lives on the same platform as other forms of tokenised money, like tokenised deposits issued by commercial banks. It also would have tokenised securities, which are programmable digital representations that are the counterpart to real securities registered in securities depositories.

“It (the unified ledger) is what brings everything together onto one programmable platform. You can execute related transactions [and] overcome the information incentive problems that have been the bane of a lot of applications of digital money.”

He elaborates: “[One] example that we deal with in some length in some chapters is supply chain finance. Now this is a well-known thorny issue in economics…and below is a very concrete example of a buyer-versus-seller type of incentive problem.

“Upstream suppliers, who tend to be smaller medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), have a great deal of difficulty integrating themselves into the financial system in a way that makes the supply chain work smoothly. What typically happens is that there is an anchor buyer – a big firm – and they need some intermediate input in order to produce their final goods. This intermediate input could come from an SME, it could come from another country, or it could be far away. It requires time for the production to take place, it needs time for the goods to be transported, and that upstream buyer, in turn, could be reliant on yet higher upstream buyers. It is a long chain.

“For the anchor buyer,” says Hyun, “ideally, they would like to only pay once the goods are delivered. If you are the upstream supplier and a small firm, you’re not flush with cash and would like to get some credit based on this.”

“Here’s a field that’s rife with fraud,” Hyun continues. “If you are an unscrupulous firm, you could approach two banks with the same order that you have received and get two lines of credit. There is no way of checking. It gets even more complicated. Suppose you ship it but…there is a storm and the goods are lost. What do you do then? For all these reasons, credit is very expensive [for the SME], if you get it at all. This is a classic example in economics where you have got an incentive problem because once you have the money, you may not want to put in the effort; then you have got information problems: you don’t know how these things are actually arranged, you don’t know who the upstream suppliers are, is it really a genuine firm?

“The ledger comes in to resolve all of these pieces. You can put everything together on one ledger as it is transparent. You can say, ‘Let us advance a small payment to the upstream supplier first to get the production going,’ and then there could be some sort of milestones that you keep track of. For example, you can rely on its global positioning system or the Internet of Things device and say, “Once the ship crosses the horn of Africa, then we will pay out the next tranche of the loan,” or “Once the ship is in the proximity to the final buyer, then we will lower the interest rate.”

What’s the potential upside to the implementation of a unified ledger?

Although Hyun admits that no one can really put a tag on this because “we don’t know how much of this is not happening because of incentive and information problems”, the existence of this level of interoperability will most certainly promote financial inclusion and level the playing field for economic actors.

Uniting the elements of tokenised deposits, tokenised assets, and CBDCs onto one platform would yield long-term benefits which far outweigh the short-term costs arising from investment, coordination efforts, and the pain of adopting to new standards and procedures.

Instead of the creation of ‘one ledger to rule them all’, the preferred approach is for incremental changes to existing systems. This can be achieved through either of these innovations:

The latter could bring about a unified ledger faster, cheaper, and with less coordination.

The BIS reports: “Depending on the needs of each jurisdiction, multiple ledgers, each with a specific use case, could coexist. APIs could connect these ledgers to each other and existing systems. Over time, they could incorporate new functions or merge as overlaps in scope expand. The scope of a unified ledger would also determine the parties involved in each ledger’s governance arrangements.”

However, there will be pain points arising from quick fixes built on top of legacy systems. Hyun emphasises: “There will be a limit to how complex it can be. Each layer needs to take into account its compatibility with the layers below. It is complex and it limits what can be done in terms of programmability. At some point, it might even be better to migrate to a new financial market infrastructure, a brand new one that can start on a clean slate.”

Tokenisation represents a significant opportunity, but it seems that finance is still at a crossroads when it comes to the financial architecture that will best serve the needs of the future.

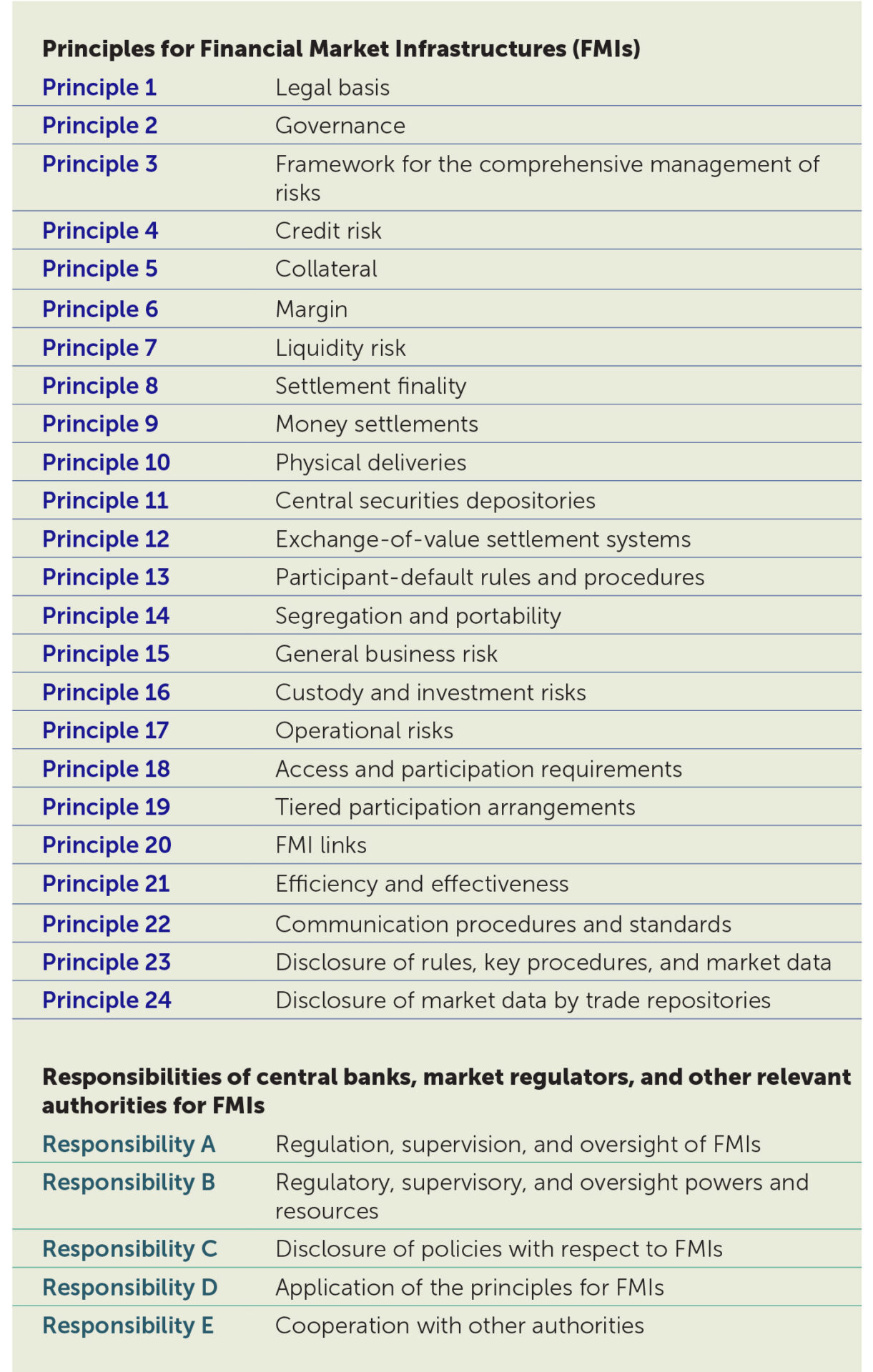

What cannot be denied is that any redesign of governance for new financial market infrastructures – including payment systems, central securities depositories, securities settlement systems, central counterparties, and trade repositories – should adhere to the standards that are clearly laid out in the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (Figure 1), a key document issued by the BIS’ Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), which is essential to strengthening and preserving financial stability.

When read in tandem with other key documents such as the Financial Stability Board’s Key Standards for Sound Financial Systems and the CPMI-IOSCO’s Application of the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures to Stablecoin Arrangements, it’s clear that although international standards can accommodate innovations in financial governance, the real acid test will be how each jurisdiction operationalises these principles to ensure the twin goals of financial stability and financial innovation are concurrently met.

Kannan Agarwal is a content analyst and writer at Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm.