The Quandary of Digital Payments

When it comes to digital payments, the near future is not so hard to predict.

By Dr Eli Remolona

With the advent of private digital payments, central banks around the world are finding themselves in a quandary. Their role in the payments system, after all, is one of their core functions, along with monetary policy and banking supervision. The quandary is about how to take advantage of the new technologies to foster payments efficiency, while maintaining the integrity of the system.

Our modern payments system has its roots in 17th century London. It was there that wealthy merchants started to store their gold with goldsmiths. Soon the goldsmiths began to issue promissory notes backed by the gold in their vaults. These notes became so widely accepted as a means of payment that the full backing of gold became unnecessary.

By the Restoration period in England, the goldsmiths had organised an unregulated system of fractional reserve banking and a payments system based on reciprocal note acceptance and interbank clearing. The goldsmiths would accept each other’s notes and keep well identified accounts for one another. As the story goes, these goldsmith-bankers would gather at the Five Bells Tavern on Lombard Street to exchange cheques and debit or credit each other’s account. This was the birth of what we now call the account-based payments system, one that requires the identification of the two parties to each transaction.

In 1694, the Bank of England was granted a royal charter to serve as banker to the crown. Even as a private bank, it would issue handwritten banknotes that became widely accepted as money. Until the 19th century, however, it did not have a monopoly of note issuance in England, and notes issued by provincial banks also circulated widely. A semblance of monopoly over fiat money was secured with the Bank Notes Act of 1833, which conferred ‘legal tender’ status on the Bank of England’s banknotes. This part of the system is what we now call the token-based payments system, one that requires no accounts in the names of the parties involved.

From those beginnings, the payments system has evolved into one where a token-based system operates side by side with an account-based system.

In 2009, Paul Volcker, the former Fed chairman, famously said, “The most important financial innovation that I have seen in the past 20 years is the automatic teller machine (ATM)…”. While Mr Volcker may have been exaggerating, the innovation he identified is about the payments system. The ATM is a technology that links the account-based system to the token-based system.

For most of the past 300 years, it is the payments technology of the Five Bells Tavern that has proved to be more innovative. The innovations have led the account-based systems to branch out into two parts, a retail part and a wholesale part.

In the wholesale part, we now have systems that process large-value payments in real time. The grandaddy of these systems is Fedwire, a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system that was launched by the US Federal Reserve in 1970. The United Kingdom followed in 1984 with an RTGS system called CHAPS, and France in the same year with a system called SAGITTAIRE. By 2005, about 90 central banks were operating RTGS systems, including CNAPS in China, RENTAS in Malaysia, PhilPaSS in the Philippines and BAHTNET in Thailand.

In the case of Fedwire, in August 2020, the RTGS system processed over US$3 trillion a day in final and irrevocable payments. By and large, these real-time payments are used for large securities transactions, allowing delivery versus payment across accounts at the Fed. There are over 7,000 well-verified accounts. In case of disruption, the Fed stands ready to provide backup liquidity.

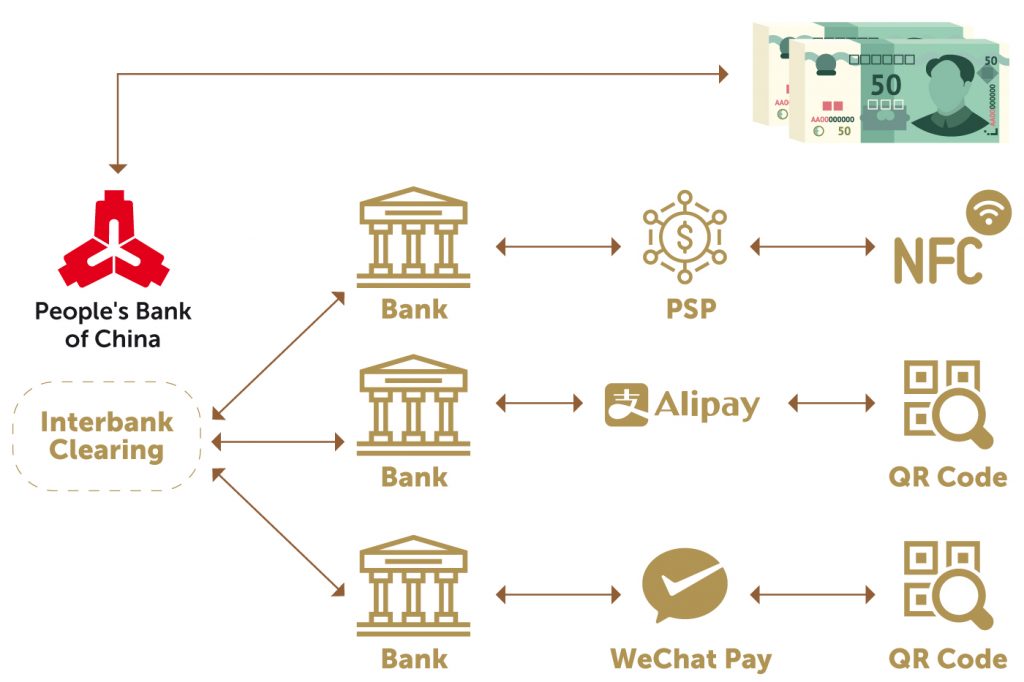

In the retail part, modern payments rely on three links of a payments chain. The diagram below depicts these three links by using the example of China’s retail payments system. The link at one end of the chain is that of intermediaries, which are typically banks. These intermediaries move funds between consumer and merchant accounts and among themselves by means of interbank clearing mechanisms, including a cheque-clearing system, a shared ATM network system, and an electronic transfers system. The next link in the chain is that of payment service providers (PSPs), which serve to authorise payments and also maintain some accounts of merchants and consumers. At the level of consumers and merchants, various forms of electronic technologies communicate with the PSPs to allow the transactions to go through.

The dominant way to communicate with PSPs used to be a magnetic strip on the back of your credit card. That has now given way to two competing technologies: near-field communication (NFC) and the QR code. Credit card payments now rely largely on the NFC technology, which allows payment by waving a card near the merchant’s device. In this case, communication with the PSP works through the merchant’s device. In China, the dominant PSPs are Alipay and WeChat Pay. They rely on the QR code technology, in which communication with the PSP works through the consumer’s smart phone. According to Aaron Klein’s article, Is China’s new payments system the future?, published by Brookings Institution, China’s experience suggests that the QR code technology is far more efficient than the NFC technology.

Distributed ledger technology (DLT) burst upon the payments scene in 2009. That was when the DLT-enabled cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, came into existence. Cryptocurrencies are digital tokens that, like banknotes, can be transferred from peer to peer without the need for accounts at intermediaries.

The introduction of Bitcoin was followed by other cryptocurrencies – Ethereum, XRP, and Tether. As of April 2020, the combined value of cryptocurrencies is estimated at US$128 billion. That is a puny amount compared with the world’s money supply. The US money supply in the form of M2 is already about US$19 trillion. On the whole, cryptocurrencies have not lived up to their hype.

The experience of Bitcoin and other permissionless cryptocurrencies has revealed two problems that make these digital tokens particularly troublesome as a means of payment. First, they are unreliable as stores of value, behaving more like speculative investments than bank deposits. Second, they are excruciatingly slow. Bitcoin’s block size limit and proof-of-work verification process reportedly allows at best only seven payments per second. Visa, by contrast, is able to process 24,000 payments per second.

The more credible challenge to the modern payments system has come from private stablecoins. These are cryptocurrencies that are designed to address the volatility of the earlier generation. Tether, for example, is a stablecoin that pegs its value to the value of a national currency, such as the US dollar.

In June 2019, the announcement of a proposed new stablecoin forced central banks to take serious notice. The announcement was that of Libra, a global stablecoin proposed by Facebook along with an “Association” of other companies. To avoid volatility, Libra would be backed by a basket of reserve currencies. To avoid long processing times, it would initially be a ‘permissioned blockchain‘ in which verification would be left to the members of the Libra Association. In April 2020, after various regulators expressed some concerns, the Association released a Libra 2.0 white paper. The revised plan promised to offer single-currency coins within a robust compliance framework and to remain a permissioned blockchain.

Seeing themselves as the custodians of the payments system, central banks have not been sitting still.

The low-hanging fruit has been to upgrade the existing interbank clearing systems. In 2018, the Eurosystem launched the TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) service, which provides payments in real time around the clock. Not to be outdone, the US Federal Reserve has been developing FedNow, a service that will similarly allow financial institutions to offer instant payments around the clock.

For many central banks, however, the most important response to cryptocurrencies has been to try to create their own central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). For the central banks, it is a process of learning by doing in a world of fast-changing technology.

In regulating the payments system and undertaking their CBDC projects, central banks have been trying to adhere to several design principles. These principles include the following:

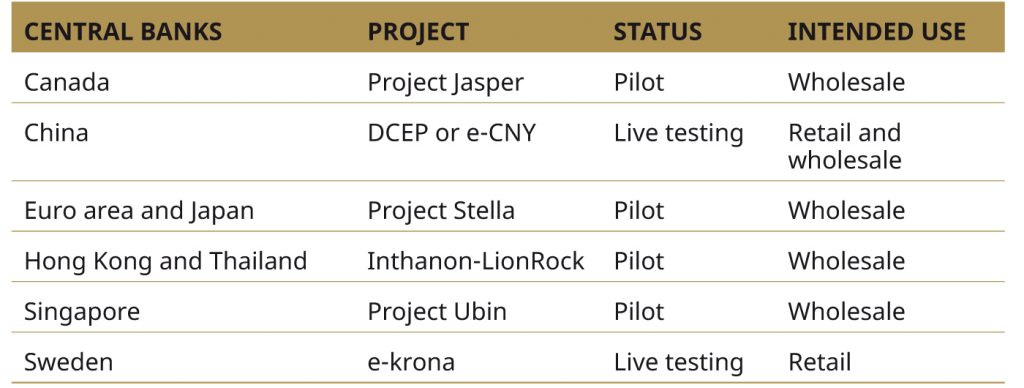

The CBDC projects themselves vary in their objectives, some focusing on retail payments and others on wholesale payments. The projects that are furthest along are those of China and Sweden. Both China’s e-CNY and Sweden’s e-krona are now in the live testing stage.

The People’s Bank of China is testing a token-based DLT with account-based elements. The use of CBDC tokens will be limited to top-tier intermediaries, which will be able to settle payments with finality through the central bank’s accounts. China is also seeking to force Alipay and WeChat Pay to make their systems interoperable.

For its part, the Swedish Riksbank is testing both an account-based and a token-based CBDC. Both will provide instant payments. However, the account-based e-krona may earn interest and will be traceable, while the token-based e-krona will allow anonymity and will not be traceable if it is prepaid.

An interesting project that is still in the pilot stage is a collaboration between the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Bank of Thailand. The project is called Inthanon-LionRock, named after mountain peaks in Thailand and Hong Kong. The objective is to transform cross-border wholesale payments, a system that has long suffered from inefficiency and settlement risk. The proposed new system will finally allow real-time cross-currency transfers with payment-versus-payment settlement.

The Forseeable Future

Yogi Berra, the American baseball player, said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” When it comes to digital payments, however, the near future is not so hard to predict. It is safe enough to say that we will see three futures in the next few years:

+ First, central banks will soon operate enhanced interbank clearing systems that will allow real-time round-the-clock payments. The European Central Bank, Bank of Korea, and Banco de Mexico are already doing so.

+ Second, central banks will offer both account-based and token-based CBDCs. The People’s Bank of China and the Swedish Riksbank are well on their way to doing so.

+ Third, a Libra stablecoin that complies with regulatory standards will be launched globally in the next year or so.

What an exciting time for payments!

Dr Eli Remolona is Professor of Finance and Director of Central Banking at the Asia School of Business. He sits on the Council of Advisers of the Academy of Finance in Hong Kong and is Associate Editor of the International Journal of Central Banking. Dr Remolona previously worked with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the Bank for International Settlements. He holds a PhD in economics from Stanford University.