Pre-empt a Green Swan

Focus on material sustainability issues to mitigate sustainability risks and achieve alpha.

By Julia Chong

Whilst alarmist reports make for good headlines, they are an incomplete reflection of the work that has been done to forestall a potential climate-related financial crisis. Reining in sustainability risks has been on the agenda for some time, but garnered little attention from media stalwarts.

Take, for instance, non-profit Ceres’ announcement that lending linked to fossil fuels and energy transition could translate into more than USD100 billion in losses for US banks and systemic financial risk. What this soundbite – carried by major newswires throughout the world – fails to reflect is the other side of the story.

In every way, sustainability policies today are the result of years of behind-the-scenes work by supervisory authorities.

The EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which came into effect on 10 March 2021, is a landmark new regulation issued by the European Supervisory Authorities to achieve the goal of a carbon-neutral Union by 2050. The Regulation is a legislative tool designed to reorient capital towards sustainable businesses in order to achieve global climate goals whilst ensuring financial institutions actively combat ‘greenwashing’ i.e. conveying a false impression or misleading information to investors that the products are environmentally friendly.

An important aspect of the SFDR, specifically Recital 10, is that it is now mandatory for financial institutions to make pre-contractual and ongoing disclosures with regard to sustainability risk to end investors in accordance with regulatory technical standards.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) define sustainability risk as an environmental, social, or governance (ESG) event or condition which could cause an actual or a potential material negative impact on the value of the investment. This provides greater protection for end investors as firms must now disclose sustainability characteristics and risks at both entity and product level in accordance with EU-issued technical standards. Otherwise, firms must explicitly state that the product or entity does not take into account sustainability risks. This is known as a ‘comply or explain’ regime.

Most European banks have in place policies and/or established frameworks to address this risk and actively inform investors how controls are in place to take into account sustainability impacts. Rothschild & Co Merchant Banking, for instance, discloses to investors how sustainability risk may occur as part of its ESG investments:

“This policy therefore approaches sustainability risk from the perspective of the risk that ESG events might cause a material negative impact on the value of our products’ investments. To give an example, if a Merchant Banking fund has significant exposure to digital services businesses which collect and process large volumes of personal data, then Merchant Banking might consider that there is a data security risk which, if a breach were to occur, could cause a material negative impact on the value of the relevant business (i.e. a governance risk to the value of the digital services business). To give a further example, if a Merchant Banking fund has significant exposure to a company which is people intensive, then any breach of applicable labour laws and employment rights could result in an adverse impact on Merchant Banking’s investment (i.e. a social risk to the value of the company).”

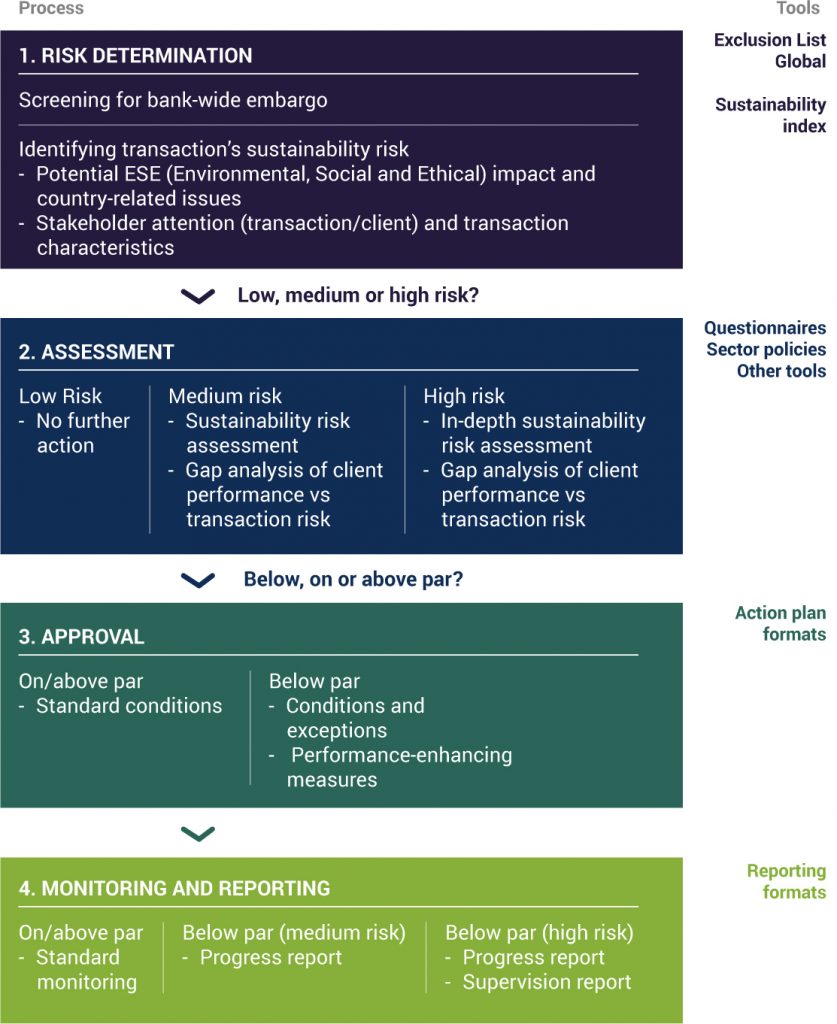

Others like ABN AMRO Bank N.V. have outlined an umbrella Sustainability Risk Policy that zooms in at the activity level to fully incorporate the policy in each of the bank’s relevant activities. For example, its Sustainability Risk Policy for Lending (Figure 1) outlines the sustainability risk management process for ABN AMRO’s lending activities in order to ensure that lending transactions are managed according to its sustainability risk appetite and the ‘Three Lines of Defence’ model (risk taking, risk oversight, risk assurance).

What warrants greater attention is: The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change, a 155-page book by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and Banque de France.

Inspired by Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s now-famous ‘black swan’, the green swan concept in this book draws similarities with the former except:

In a January 2020 podcast, Luiz A Pereira da Silva, BIS Deputy General Manager and co-author of Green Swan, describes two types of sustainability risk – physical and transition – and ways to preserve financial stability in the era of climate change:

“We are, of course, already seeing many of the physical risks associated with climate change. Take, for example, the widely noticed wildfires in Australia, or some of the consequences of hurricanes in the Caribbean…of course, for communities, these events entail large cost.

“Now, if we start rushing into very sudden changes, for example, regulations to offset these events – which is needed, but we do it in a way that is abrupt, that causes people to change portfolio allocations of their assets in a very fast, rapid way – we run into the risk of transitions that are not controlled.

“In an ironic sense, if we are successful in changing some of the regulation for the common good, to reduce the risk of climate change, we might run into the paradox of creating [for] ourselves some financial consequences that might be negative.

“So, everybody has to consider walking a very thin line between the urgency of making changes that improve and combat climate change, while at the same time considering all the consequences of this and trying to make sure that we move in the right direction, with safety and for the common good.”

Such gradual moves, says Pereira da Silva, requires more novel approaches to risk modelling: “What we are increasingly perceiving is that all these phenomena related to climate change are very complex. They contain nonlinearities, they contain a number of different locations, and therefore, they are very uncertain.”

“Now, most of the models that we use and sometimes models that include climate related events to forecast financial stability, they are usually backward looking. And now we understand that none of them contain climate related risks of the magnitude that we have today. So, we need to use more and more novel approaches, forward-looking scenarios that instead of just trying to replicate the past, extrapolate from the knowledge that we are accumulating with climate scientists, and that show that the dynamic effects of what is happening, the accumulation of greenhouse gas effects into our environment is changing dramatically and with a lot of uncertainty, the way in which we see the future. So, it’s much more complicated than just extrapolating the tendencies of the past.”

Some quarters, including former Secretary General of the Basel Committee Bill Coen, argue that climate change is being used as a justification to rollback established banking standards. Pereira da Silva refutes this logic and points out that addressing sustainability risk does not diminish financial stability, but instead improves it.

“What we are adding now is an additional dimension that needs to be carefully thought through. So that you begin thinking of what are the dimensions in terms of the composition of assets that your financial system has that entails more or less climate related risks, and the financial stability consequences of holding these assets,” he said.

It’s necessary to note that although climate-related systemic risk has received the most attention of all the ESG trends, other factors such as gender and racial diversity, biodiversity, food security, human rights, and global pandemics are part of the larger picture. Similar to the ‘Do No Significant Harm’ principle in the EU Taxonomy (see Many Markets, One Common Language), these factors are interdependent with varying degrees of materiality.

The importance of materiality is exemplified in Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality, a seminal 2019 paper by Harvard Business School’s Professor George Serafeim and coauthors, which discovered that firms with good ratings on material sustainability issues financially outperform firms with poor ratings on the same issues. Designing an index that differentiates between material sustainability issues and immaterial ones, the research indicated that the former yielded strong results with estimated alpha ranging from about 3% to 5% annualised. They conclude that these findings have “implications for asset managers who have committed to the integration of sustainability factors in their capital allocation decisions”.

A 2019 research report commissioned by the Global Alliance for Banking on Values, an independent network of banks and banking cooperatives, found that banks which consistently scored high on material ESG issues delivered higher risk adjusted returns compared to those banks that performed poorly on the same issues, while the opposite was found for immaterial ESG issues. These results suggest that a focus on material sustainability issues is likely to coincide with enhanced financial returns.

If the deal is then sealed that sustainable investments will pay off in the long run, what remains to be seen is whether financial institutions will commit themselves to ESG principles in the short- to medium-term transition toward a sustainable future.

In this respect, Pereira da Silva’s words exemplify the approach that all financial players should take in order to avoid a potential green swan: “Central banks cannot do it alone. They have to coordinate the actions of others because the fight against climate change is a collective action issue. Everybody in society should pull in the right direction.”

Julia Chong is a Singapore-based writer with Akasaa. She specialises in compliance and risk management issues in finance.