Move Along, Goldilocks

Forget about the economic sweet spot. Fundamentals are what we want.

By Angela SP Yap

Sometime in September 2020 – or about nine months into the pandemic – overt signs of market rallying entered mainstream media. Headlines like “Get ready for Goldilocks phase in 2021” and “Indonesia, Philippines well-placed for Asia’s Goldilocks phase in 2021” were premised on a single report by a global investment bank which primed investors for “a sweet spot of accelerating and above-trend growth, rising-to-trend inflation, and a big easy policy”.

From thereon, others began chiming in. In a letter to shareholders issued in April, one financial chief iterated “it is possible that we will have a Goldilocks moment”. As recent as 27 October, the release of the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s budget was likened by news agency Reuters as ‘Rishi Sunak Bets on Goldilocks Economy’.

When it was clear that predictions had run astray, one analyst, also speaking to news agency Reuters, introduced a new term – the “semi-Goldilocks” moment. A good soundbite, for sure, but this hair-splitting term defies logic to any analyst worth his or her salt. What will they conjure up next – a quarter Goldilocks?

As 2021 comes to a close, for those who’ve been waiting for the Goldilocks gravy train to arrive, we’re here to remind that banking is built on sterner stuff. Sweet spots like Goldilocks are fleeting moments whereas the road to economic recovery is paved in fundamentals.

Coined by UCLA senior economist David Shulman in his equity-strategy paper The Goldilocks Economy: Keeping the Bears at Bay, the eponymous term taken from a children’s fairy tale has been embedded in financial lexicon to denote an economy that’s like that third bowl of porridge in the story: just right – not too hot, not too cold.

While there’s really no hard and fast rule when it comes to defining the parameters of a Goldilocks economy, consensus dictates a precarious balance (some describe it as a knife’s edge) typified by low unemployment rate, increase in asset prices, low market interest rates, low inflation, and steady economic growth. In other words, it is the ideal state where economic growth is, as one bank put it, “warm enough to keep a recession at bay but cool enough to stave off major inflation”. The trifecta to every investor’s dream.

However, like the law of gravity, nothing stays buoyant forever. A Goldilocks economy is temporary and part of the boom-and-bust cycle. What few will tell you is that the choices you make during this fleeting moment will leave a lasting impact in your organisation and an indelible ripple effect throughout the financial system.

As more countries – especially in emerging markets – move towards greater economic stabilisation after the stress of a crisis, financial institutions are driven to take on more risk in search of greater yield.

It bears reminding that bets that turn sour have knock-on effects. In this regard, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned of the impact such strategies have on economic and financial stability, caused by banks that take on inordinate risks in the hopes of securing the greatest returns on investment.

The Risk & Return: In Search of Yield, an article published in the IMF’s autumn issue of Finance & Development magazine, connects the dots between a firm’s investing strategies and its implications for financial stability:

“Low rates of return tempt investors to take risks, which can cause economic and financial instability.

“Firms might seek to boost income through speculative investments financed by debt because borrowing is cheap. Financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies may make risky bets to maintain profits or even to survive. But riskier portfolios increase the likelihood of loss. Higher indebtedness means firms are in a more precarious position when confronted by adverse shocks. The result is greater institutional vulnerability and increased likelihood of economic and financial instability.

“Like firms, financial institutions deploy different search-for-yield strategies. Large banks may expand abroad to countries where growth and investment returns are brighter. Mid-sized banks may expand domestically, across sectors or regions, taking business from smaller local lenders. Smaller banks, for their part, may merge or partner with mid-sized banks, or with each other, to fend off the competition.

“Economists do not oppose risk-taking to boost returns per se: some individuals and institutions are better at managing risk than others, and risk-taking does not necessarily imperil economic growth and financial stability. However, search-for-yield strategies can have system-wide consequences if they are widely adopted by firms and financial institutions. This would concern policymakers.”

The global economy isn’t out of the woods yet. Hence, it’s important to not bite off more than one can chew, especially when banks are critical in ensuring the world’s economic engine continues to hum amidst the turmoil of the past 20 months.

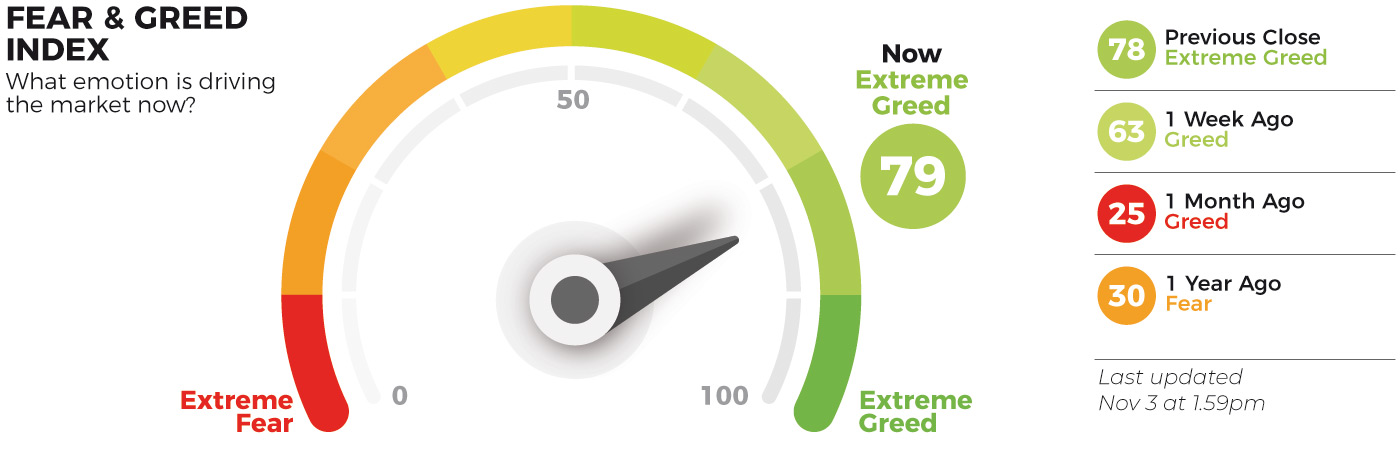

We can detect the undercurrents of market anxiety through less conventional measures. For instance, CNN Money’s Fear & Greed Index, which looks at seven emotion indicators driving investor decisions. As at 3 November 2021, the index stood at 79 (indicating extreme greed) compared to its year-ago reading of 30 (indicating extreme fear). Too much fear sinks stocks below their fair value while too much greed will bid stock prices above fundamentals. At the moment, we’re far from balanced in our approach.

Such anxiety in search of the highest yield has not gone unnoticed by analysts like Citigroup’s Chief of US equity Tobias Levkovich, who warned against a possible repeat of the dot-com bubble of the 1990s: “There’s a 1999 perspective being noted with pressure for fund managers to participate in rising share prices even if there’s also a recognition that it could end badly.”

Back in 1992, when Shulman’s Goldilocks research was done in his capacity as Salomon Brothers’ chief equity strategist, he already had an unpopular reputation on the Street for being uncharacteristically bearish in a bull market.

However, during the dot-com bubble, he was also one of the few analysts invited to meet with the then Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan for the market’s take on tech stocks and bonds. Two days later, Greenspan famously used the phrase “irrational exuberance” – referring to investor enthusiasm driving assets prices beyond sound fundamentals – in his speech at the American Enterprise Institute. Within hours, pundits scrambled to sell off tech stocks deemed to have gotten ‘too hot’, restoring some measure of short-lived balance in the market.

Today, the bubble-bursting torch may well have been passed on to economist Nouriel Roubini, who is no stranger to controversy as one of the few who predicted the subprime market crash of 2008. His op-ed, Goldilocks is Dying, which debuted online this September via Project Syndicate, outlined four scenarios of how the global economy and markets could play out in the next year: Goldilocks, ongoing stagflation, growth slowdown, or overheating. Roubini’s pick? The last scenario.

He writes: “While most market analysts and policymakers have been pushing the Goldilocks scenario, my fear is that the overheating scenario is more salient….The Panglossian scenario that is currently priced into financial markets may eventually turn out to be a pipe dream. Rather than fixating on Goldilocks, economic observers should remember Cassandra, whose warnings were ignored until it was too late.”

This metaphor is full of meaning. In Greek mythology, Cassandra is a princess blessed with the gift of prophecy but cursed that no one would believe her. She represents humanity’s moral conscience. When her name is invoked in a corporate context, it is always in the hope that the powers-that-be in the organisation will pay heed and avert a catastrophe.

Indeed, Corporate Cassandras have a critical role to play in managing business risk and leading organisations through strategic inflection points. Take it from Richard Clarke, the US counterterrorism chief whose warnings about al-Qaeda and 9/11 were dismissed by the then president because it had never happened before.

In an interview with Harvard Business Review, Clark dispensed this simple advice on how corporations can embrace the Cassandras in their midst and elevate performance:

“When somebody who may be a Cassandra in your organisation has predicted something, and it’s never happened before, and you don’t really know whether or not to trust their data, don’t be dismissive.

“Take what we call a surveillance and hedging strategy. Surveillance meaning, put the issue under watch, see if the data begins to change, and if so, in what direction. Meanwhile, spend a little bit of money planning what you would do if you became convinced that the Cassandra was right. It doesn’t cost a lot of money to plan and if the data starts shifting in their direction, increase the amount of planning, increase the preventative measures – you don’t have to make a decision all at once. You can experiment. You can keep it under watch.”

The obsession over Goldilocks moments will fade into obscurity when we train our sights on bigger and more long-term goals. After all, little has ever come out of pursuing a fairy tale.

Angela SP Yap is a multi-award-winning social entrepreneur, author, and former financial columnist. She is Director and Founder of Akasaa, a boutique content development firm present in Malaysia, Singapore, the UK, and holds a BSc (Hons) Economics.