Brand Loyalty Has a New Metric

Does the NPS move over for the new kid in town?

By Julia Chong

In 1993, Fred Reichheld introduced the concept of the Net Promoter Score (NPS) in his book, Loyalty Rules! How Today’s Leaders Build Lasting Relationships, a work that has since been credited with putting loyalty economics on the map of business management.

Since then, the NPS has entered mainstream lexicon and is one of the few metrics relied on by organisations to measure customer experience (CX) and determine brand loyalty, aspects which, in turn, bear down on growth figures. The simplicity of the NPS made it hugely popular and today it is unquestioningly (or blindly) incorporated into every customer survey platform.

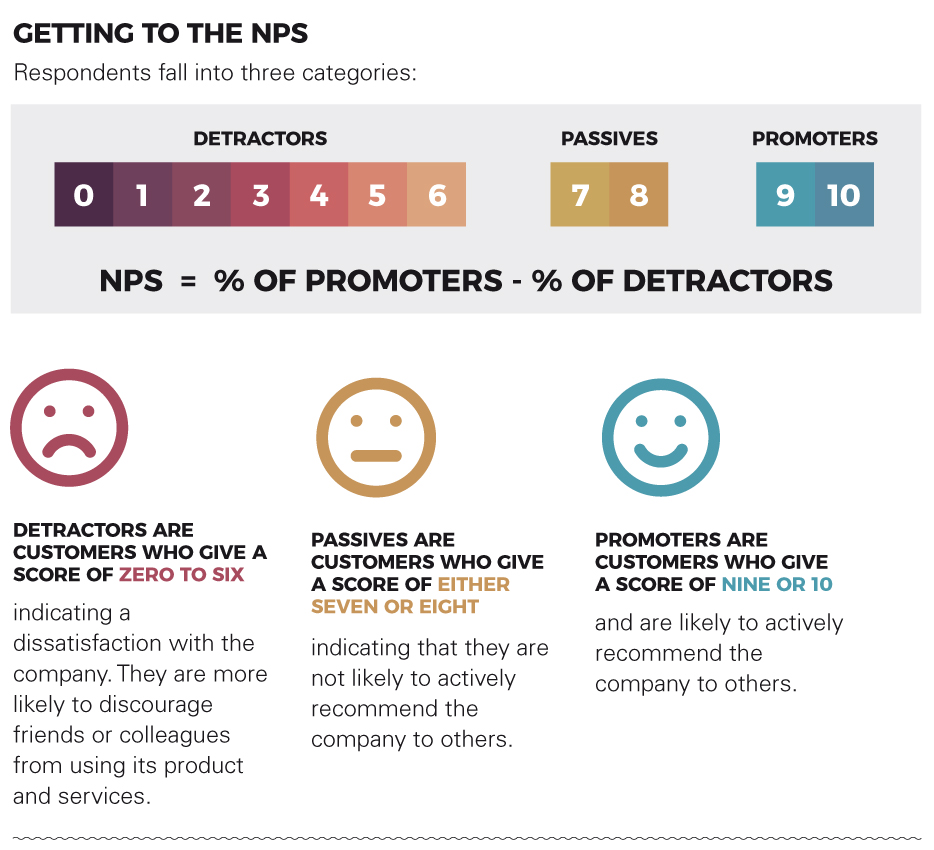

The research was simple. Thousands of customers in six industries were sent a series of 20 questions, an acid test to gauge loyalty. The results showed that one question stood out with the highest correlation as to whether a customer would be a detractor or promoter of the business. That question is: On a scale of one to 10, how likely is it that you would recommend this company to a friend or colleague?

Then take the percentage of promoters and subtract the percentage of detractors. This will generate a score ranging from -100 to 100, which is the NPS. A positive NPS means that you have more people recommending the company or product organically than people discouraging others from the company, while a negative score means the opposite.

Sources: Adapted from Zendesk, Survey Monkey.

However, after three decades, the cracks in the NPS are evident not only to legit practitioners in the CX sphere, but the creator himself who has spoken out against the abuse and misuse of the metric. Reichheld states that two-thirds of Fortune 1,000 companies report the NPS yet only 5% derive its full benefits. Here’s why:

+ Companies started using NPS as a metric to justify bonuses. Whilst this doesn’t seem like a red flag, employees started finding ways to game the system. These tactics have been subject of much research, including Rob Markey’s Harvard Business Review article, The Dangers of Linking Pay to Customer Feedback, in which he writes: “With incentive compensation, you get exactly – and only – what you pay for. Once compensation depends on improving a particular score, people tend to focus on the metric rather than on what it tells you about what customers want or need.”

Linking the NPS to remuneration incentivises poor behaviour, skewing employee goals from “what does the customer want or need?” to “how do I score higher?”. This happens in many ways: employees would nudge customers on the survey at the end of the call with “rate me a 10 if you like my service”; managers warn that “if there’s any reason why you won’t rate me a 10, please let me know before giving feedback”; and customer service would only poll nice customers in easy-to-solve cases.

+ Declaring NPS in annual reports without an auditable or comparable process. Many multinationals declare the NPS as part of their annual report, a misleading move as it creates the impression that the NPS is of a standard comparable to financial figures governed by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) rules and financial reporting regulations. It is not. Many companies have deviated from the standard response scale and formulation of questions, whilst others diverge too much from the official standard NPS question. Far from being an industry benchmark for delightful customer service, its gaps in the data collection process make the NPS unsuitable for any benchmarking exercise.

+ Customers lose faith when they don’t see follow through. When the NPS is executed as a standalone metric or is not embedded as part of a product roadmap to enhance customer experience, the entire exercise fails to elevate the brand or transform into meaningful change.

Given these drawbacks, Reichheld’s article in the December 2021 issue of Harvard Business Review marked the coming of a new metric, the earned growth rate (EGR), in which he and his co-authors set out to correct the drawbacks of the NPS by developing “a complementary metric that drew on accounting results”.

In Net Promoter 3.0, Reichheld et al outline “a better system for understanding the real value of happy customers” through calculation of the EGR, which has two building blocks:

#1 Net revenue retention (NRR): This statistic is used in several industries, most notably in software-as-a-service. Once you have organised revenues by customer, you can determine your NRR. Simply tally this year’s revenue from customers who were with you last year, divide that amount by last year’s total revenue, and express that figure as a percentage.

#2 Earned new customers (ENC): This is the percentage of spending from new customers you’ve earned through referrals (as opposed to bought through promotional channels). This component will take a bit more effort because firms must ascertain why new customers have come on board. While it may require some experimentation and refinement, ENC is important to track. The sooner you have a reasonable estimate of revenues from ENC, you can better focus your customer acquisition investments — and justify more investment in delighting current customers. Firms today undervalue referrals. They treat them as icing on the cake rather than an essential (perhaps the most essential) ingredient for sustainable growth.

Once these two elements are in place, apply these into the calculation:

EGR = (NRR + ENC) – 100%

The creators also state that the EGR complements the NPS. Their book, Winning on Purpose: The Unbeatable Strategy of Loving Customers, details the intricacies of deriving the individual statistics of the NRR and ENC, and how to interpret the EGR results on standalone basis as well as in tandem with the NPS.

Given the current technical challenges and information asymmetry that come with implementing the EGR, it is too soon to determine whether corporations take to it the way they did with the NPS. It is proof that brand loyalty and CX are moving the way of ‘hard science’ and it bears reminding that there are no silver-bullet metrics in any science.

Julia Chong is a Singapore-based researcher with Akasaa, a boutique content development firm with presence in Malaysia, Singapore, and the UK.