Web 3.0: Should You Care?

What it is, what it could be, why it matters.

By Kannan Agarwal

In the 1990s, less than 1% of the global population had access to the internet. Today, that figure has leapt to 59.5%, equivalent to 4.66 billion people, with 92.6% of them accessing it via their mobile devices, according to Statista.

This ever-growing digital footprint has resulted in an unprecedented number of breach-of-privacy scandals – Cambridge Analytica, LinkedIn, Equifax, to name a few. Unsurprisingly, McKinsey & Co’s recent survey of American consumers found that more than 50% of consumers do not trust the companies and brands they patronise – including financial institutions – to protect their private data. Other perception surveys around the world point to the same.

It is no wonder that many are now opting to either deactivate their social media user accounts in attempts to reduce their digital footprints or move towards an upcoming third generation of the internet known as Web 3.0, in order to protect their data from the companies who access and may even be profiting from it.

So, what exactly is Web 3.0?

Although inventors like Nikola Tesla had visions of a “world wireless system” as early as the 1900s, it wasn’t until the 1980s, when British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee invented the world wide web (or ‘www’ as we know it today) that the online world manifested into something tangible, comprehensible, and useful for the everyday man.

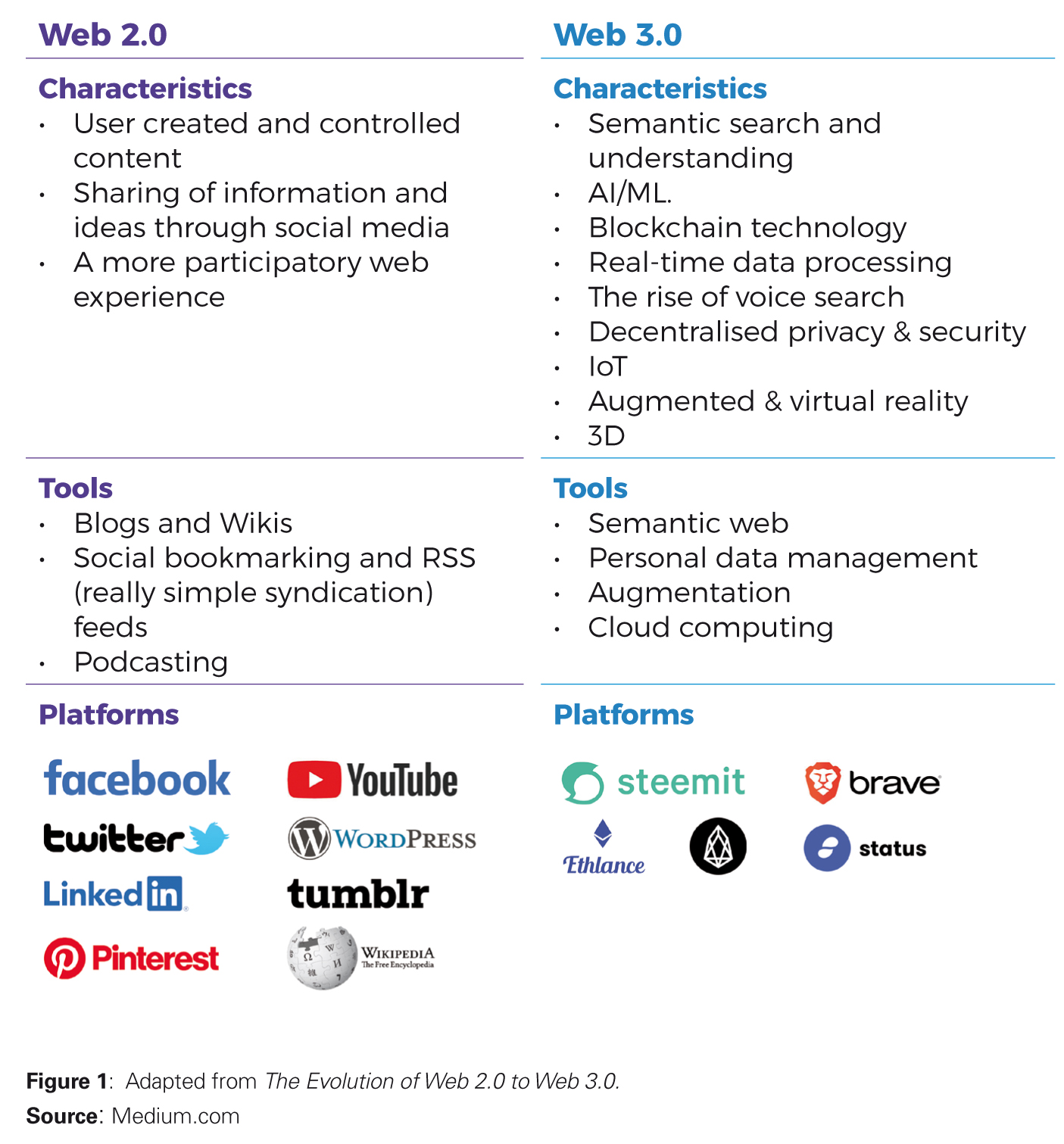

This early version is considered Web 1.0, static websites where data is accessible online and information is pushed to users; no interaction, no engagement. Browsers like Netscape and MSN contained millions of ‘read only’ websites that were built for the sole purpose of sharing information with a large audience, an information superhighway that was a massive collection of content oligopolised by phone companies and cable networks. Millennials today will snicker looking at an old-school Yahoo browser with word-only search capabilities (a far cry from Google Lens and other interactive features that are commonplace today), but back then, the notion that you could get information any time, any day while sitting at your desk was nothing short of revolutionary. It led to a frenzy of interest and speculative investing in all internet-based businesses, which eventually resulted in the dotcom crash in 2000.

With millions of investors having crashed and burned in that encounter, interest in the internet waned. It was only around 2007, when the next disruption of the internet went mainstream and the tech sector started getting hot again. This is Web 2.0, a transition from basic read/write functions to social networks; the internet was abuzz and became the place for people to virtually gather, interact, and collaborate. The exponential rise in blogs, online fora, private chatrooms, wikis became de rigeur.

By today’s standards, if you don’t have a social network footprint on one of the main social media platforms – Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, Twitter, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, Tik Tok – your social currency goes down and for many, it means you just don’t exist.

Businesses have jumped onto the bandwagon and benefited from its collaborative nature: near-instant communication, direct exchange with customers, increased efficiency through process automation embedded on these social platforms, and the rise of social influencers who work with brands to drive sales for products and services.

However, this disruption has its downside. Web 2.0 has resulted in the rise of a new breed of oligopolists – Big Tech corporations like Facebook, Amazon, Google that hold inordinate power over the private user data. Such digital information concentrated in the hands of a few technology platforms have given rise to scandals and hacks with far-reaching consequences. Loss of privacy, control over personal information, biased search algorithms – are these worthwhile trade-offs for the sake of greater connectivity and convenience?

For the growing number of individuals who have been hacked, spammed, or victims of identity theft, the answer is a clear ‘no’. In 2018, it was reported that 44% of users aged 18 to 29 deleted the Facebook app from their phones and 54% adjusted their privacy settings, in a poll by Pew Research. That figure has undoubtedly increased over the years and users switch off or tune out from social media platforms.

Enter Web 3.0, also known as the spatial web or metaverse. In this next-gen model of the internet, power shifts from Big Tech to individual users in decentralised, aggregated models. Some have described it as the ‘read/write/own’ phase where users manage and operate data on their own terms, wresting back power from tech corporations.

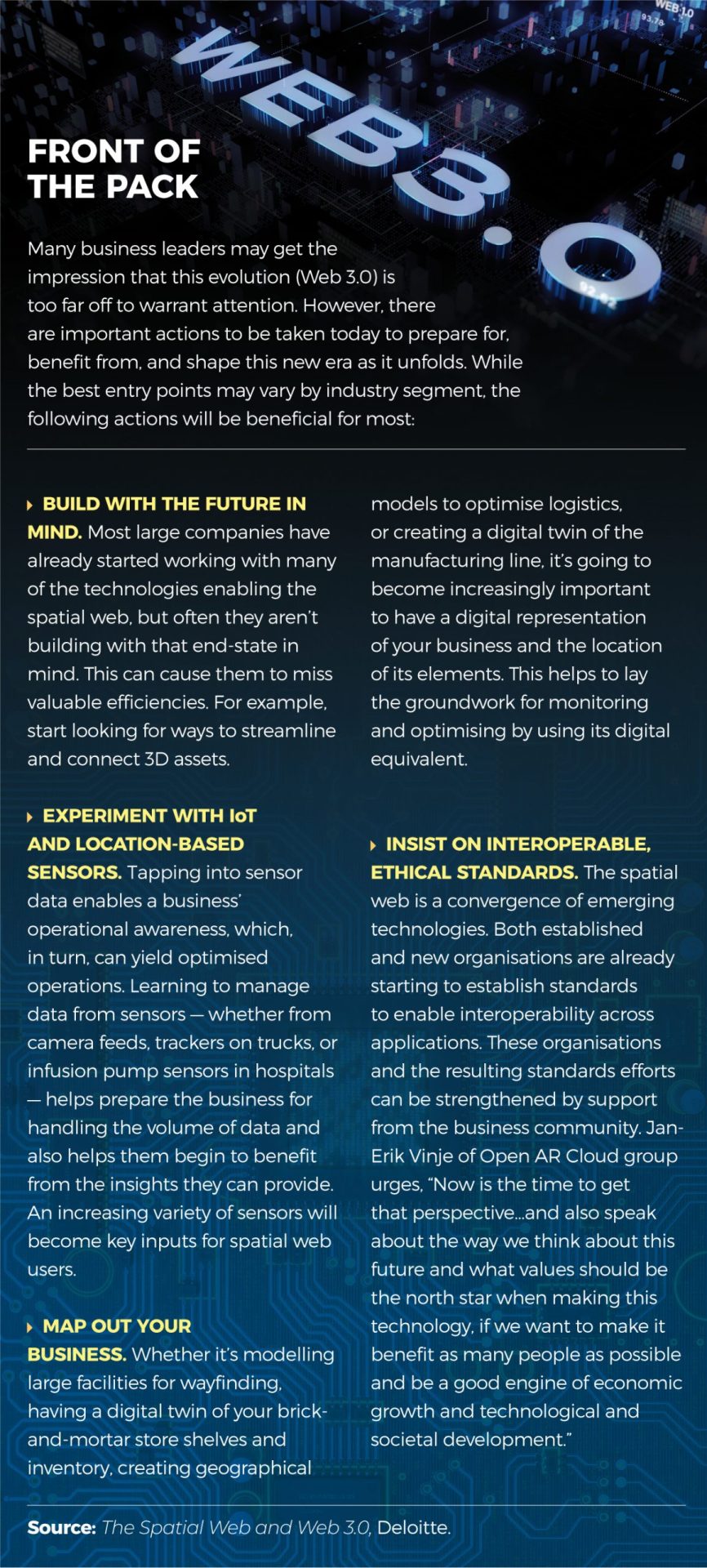

In a Deloitte report, The Spatial Web and Web 3.0: What Business Leaders Should Know About the Next Era of Computing, the consulting firm writes that it is “for leaders to understand what this next era of computing entails, how it could transform businesses, and how it can create new value as it unfolds”.

“It is the next evolution in computing and information technology, on the same trajectory that began with Web 1.0 and our current Web 2.0. We are now seeing the spatial web unfold, which will eventually eliminate the boundary between digital content and physical objects that we know today. We call it ‘spatial’ because digital information will exist in space, integrated and inseparable from the physical world.

“This vision will be realised through the growth and convergence of enabling technologies, including augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), advanced networking (e.g. 5G), geolocation, IoT (Internet of Things) devices and sensors, distributed ledger technology (e.g. blockchain), and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML). While estimates predict the full realisation of the spatial web may be 5–10 years away, many early-stage applications are already driving significant competitive advantage.”

If this sounds a little out of this world, that’s because in many ways it still is. Even seasoned tech savants like Elon Musk, Co-founder and CEO of Tesla and SpaceX who revolutionised car and space travel, has gone on the record to say “I currently am unable to see a compelling metaverse situation” and that Web 3.0 is “more marketing than reality”. His voice is chief in the chorus of notable tech visionaries tempering the hype that others are keen to whip up.

Musk’s cryptic comments highlight the frivolity of many use-cases and the disappointing experiences that currently dominate the metaverse discussion: “Sure you can put a TV on your nose, but I’m not sure that makes you ‘in the metaverse’. I don’t see someone strapping a frigging screen to their face all day and not wanting to ever leave. That seems…no way.”

With the pace of technological change today though, regulators are not leaving much to chance and already discussing what a democratised internet could mean for decentralised finance – the distributed ledger technology underpinning cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and ethereum – or DeFi for short.

In his panel remarks about Decentralised Finance and the Future of Money delivered at the Andrew Crockett Memorial Lecture via livestream in June 2021, Ravi Menon, Managing Director at the Monetary Authority of Singapore, notes how central banks and regulators can shape DeFi by incorporating Web 3.0 as part of an ever-growing fintech strategy that will uphold financial resilience and stability:

“Technology is enabling a fundamentally different approach to financial infrastructure, compared to the centralised systems of today. Take, for example, open crypto networks based on self-executing smart contracts and non-custodial financial services, where users maintain control over their assets at all times. By replacing intermediaries and central parties, these networks aim to reduce both the cost and risk of finance.”

“By decentralising key aspects of financial infrastructure, such as access, data, and code, open crypto networks can also potentially enhance inclusion and innovation. When firms of all sizes, and even individuals, can directly access financial infrastructure, it could mean more competition and inclusion. When transaction data is available to all participants, and not confined within the intermediary responsible for the transaction as is the case today, it could mean more contestability and transparency. When code can run directly and publicly on these networks, unlike proprietary code that runs on private servers, it could mean more interoperability and innovation.

Although his comments are specific to DeFi, the approach can be applied to almost all other aspects of governing the metaverse. However, like Musk says, the metaverse is still far off from being deployed in everyday life in droves. Even though it is not the place of regulators to pre-empt innovation in markets, they are aware that they must be in sync with the latest tech in order to supervise its development and guide where necessary.

Menon acknowledges the opportunities as well as challenges that Web 3.0 poses, and is already concerned with next-gen infrastructure in finance: “We are certainly not at the point where these self-governing networks can meet the high standards of governance, security, resilience that we demand of critical infrastructure. Even so, central banks would do well to incorporate these innovations in designing the next generation of payment infrastructure.”

Kannan Agarwal is a Singapore-based researcher with Akasaa, a boutique content development firm with presence in Malaysia, Singapore, and the UK.