Creative Coach, Hallucinating Help, or Misleading Muse?

Generative AI has a lot to offer, but it can’t yet tell the difference between fact, fiction, and fantasy.

By Dr Amanda Salter

In recent headlines: “Microsoft to invest USD10 billion in OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT.”

“Google invests USD300 million in artificial intelligence start-up Anthropic.”

“Salesforce Ventures launches USD250 million generative AI fund.”

The more cautious amongst us might be tempted to roll our eyes and dismiss generative artificial intelligence (GAI) as yet another flash in the technology pan, like the metaverse and non-fungible tokens. But as Forrester Research predicts in their recent trends report titled Generative AI Prompts Productivity, Imagination, and Innovation in the Enterprise, ignoring GAI would be a costly mistake.

For the uninitiated, GAI is next-level AI that automatically creates content such as artwork, music, text, videos, programming code, and simulations in response to conversational input (also known as ‘prompts’) from the user. Its output mimics original content and can appear highly realistic and plausible. Popular GAI tools to date include ChatGPT (a language generator) and Midjourney (an image generator).

GAI is a leap forward from traditional AI, like simple chatbots or voice assistants which respond to one request with one pre-prepared answer. In contrast, GAI tools retain information as a conversation progresses and refine their answers further according to new information. This enables users to participate in the creation process by asking for changes iteratively.

The ability of language generators to mimic human-created content is both surprising and slightly unnerving. It can take a job description and a CV and write a relevant application cover letter. ChatGPT has passed university law exams and even an MBA course at Wharton School of Business, achieving grades ranging from a ‘B’ to ‘C+’. There is also significant success with image generators – an artwork generated using Midjourney won first place at a digital art contest in Colorado last August.

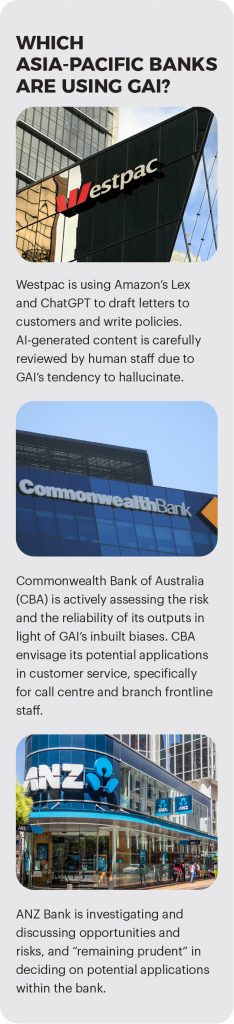

Nevertheless, the GAI race has resulted in some embarrassing casualties. Meta’s GAI, Galactica, survived in the wild for three days before being taken offline, reportedly due to generating dangerous and incorrect information for its target users in the scientific research community. Alphabet’s market value nosedived by USD100 billion when its GAI, Bard, provided a factually incorrect answer to a question asked in a widely publicised company demo. JP Morgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and Citigroup have banned the use of ChatGPT due to factual inaccuracies and associated risks.

In January 2023, ChatGPT went on record as the fastest-growing consumer application in history, with 100 million monthly active users. Regulators are striving to keep up and there are several debates and discussions happening. In the European Union, the AI Act has been trundling through the system since April 2021, but the rise of ChatGPT is forcing Parliament’s hand. Lawmakers are currently debating whether unsupervised generative language tools should be defined as ‘high risk’ in the Act, with more restrictive legislation as a result. Stricter regulations mean that developers and users of GAI tools must take more responsibility to manage risks and be transparent about usage.

Amusingly, ChatGPT-authored output recently featured in European Parliament to stress the importance of regulating AI. At a plenary session this February, Member of Parliament Damian Boeselager read out a Shakespeare-style poem that ChatGPT had generated on this topic, including the mellifluous couplet, “We cannot stand idle and let it be / But must regulate it, lest it harm thee”. Tongue in cheek perhaps, but an apt demonstration of the very capabilities we are seeking to control.

At the upcoming Point Zero Forum 2023 – a policy-technology dialogue comprising over 1,000 central bankers, regulators, and industry leaders in Zurich – GAI in banking features as one of three main agenda points up for discussion. The forum, jointly organised by Switzerland’s State Secretariat for International Finance and the Monetary Authority of Singapore-funded Elevandi, will discuss the potential uses for GAI in financial services and set out a roadmap towards navigating and adopting this technology.

If banks can find a way to safely make use of GAI, many avenues for creative and time-saving applications open up.

Language generators such as ChatGPT can produce common content in seconds, ideal for labour-intensive, low-risk, repeatable content creation tasks, such as call centre scripts, corporate policies, knowledge base articles, standard operating procedures, or summaries of longer documents. If given extra information – such as customer profiles, tone of voice, and decisioning criteria – language generators can also produce on-brand personalised customer messaging and offers, including marketing campaigns, email templates, and letter copy.

One challenge faced by Asia-Pacific banks is the plethora of regional languages and dialects, which can incur content translation time and cost. Language generators can produce translations of a text in multiple languages at one go, using prompts such as ‘translate the following text into Thai, Vietnamese, Bahasa Indonesia and Mandarin’.

Tailored images for marketing campaigns, websites, or brochures can be created almost instantly by image generators such as Midjourney. Uploading separate images of a man and a car will return several combined images that each show a man with a car. These can be further refined by adding keywords such as ‘in the style of da Vinci, at night, in a city’.

Language generators can be a springboard for creative ideas. A prompt such as ‘give me 10 innovative ways for a bank to reach rural underbanked customers’ can yield a starter set of ideas for consideration and further brainstorming.

Where feasible, banks can also incorporate language generators into internal systems to provide improved conversational content for customer support staff and chatbots for banking customers.

Teams from operations, IT, risk modelling, and business continuity can benefit from realistic stress-test scenarios that can be quickly generated at scale. An internal business resilience programme could use prompts such as ‘I am a retail bank based in Singapore with physical branches as well as online banking. Simulate a scenario to test my business resilience’.

Similarly, customer contact simulations can be generated to help train front-facing staff, from financial advisors to cashiers. Prompts can include the financial, socioeconomic, and even the emotional state of the customer, to which a language generator can role play to produce multiple realistic scenarios of customer contact.

So how does the ‘magic’ work? GAI tools are trained on vast quantities of data, both text and images. This enables them to construct a probable matching answer. The tool does not truly understand what it receives, or even what it returns to the user. It simply selects the answer that has the highest probability of being correct.

Language generators have been described as being “autocomplete on steroids”. This can lead to incorrect answers delivered with extreme confidence. When ChatGPT was asked, “If one woman takes nine months to make a baby, how long will it take nine women to make one baby?”, it confidently stated that “nine women will take one month to make a baby, if they work together”, illustrating the point that these tools do not truly understand the actual meaning of the words they are taking in or giving out.

Language generators tend to ‘hallucinate’, an emotive word, but one that suitably conveys the extreme realism and specificity of their incorrect responses. There are many recorded cases where ChatGPT has not only presented incorrect answers, but has fabricated an entire alternative history for something by replacing facts with fiction; manufacturing plausible-sounding names, events, numbers, and dates; attributing non-existent references; and continuing to justify its untruths despite being challenged.

GAI tools are typically trained on material from the internet, thus they absorb the behavioural biases of society. There are many recorded examples where language generators have returned racist, sexist, immoral, or illegal answers, and image generators have also returned highly sexualised images of the subjects requested. A generator’s knowledge of the world is restricted to the particular time frame of information it has been trained on. For instance, ChatGPT’s knowledge cutoff is September 2021 and it has no awareness of recent events.

Therefore, all AI-generated texts must be fact-checked carefully by an alert and knowledgeable human because the authoritative tone of the output can lull readers into a false sense of security. Image generation can also be hit-and-miss. Mistakes made by image generators can be much easier to detect, however, good quality AI-generated images and videos can be extremely convincing, leading to the issue of ‘deepfakes’, where a person in one image or video can be replaced by another and used for misinformation.

Philosophical and legal questions have also been raised. Who is the author of AI-generated content? Who should be held responsible if the content is wrong? Who owns the copyright for an AI-generated artwork? Who is to be sued if said artwork infringes the copyright of another? Tools are already emerging to detect AI-generated text and debates are ongoing about whether schoolchildren should be allowed to use language generators in a learning context.

GAI also brings up data security issues. For example, consider a programmer who uploads some code and requests for it to be debugged, or an executive who uploads a lengthy merger and acquisition document and asks for it to be summarised. These documents, together with the responses generated, would then reside on any one of the GAI servers and could be included in its response to other users’ prompts.

Any data, photos, or text uploaded as input to these tools can cause a security risk. Nevertheless, there are already reports that China’s Tencent is working on a tool called HunyuanAide, in a race against Alibaba and Baidu to create a domestic version of ChatGPT, which is currently banned in China.

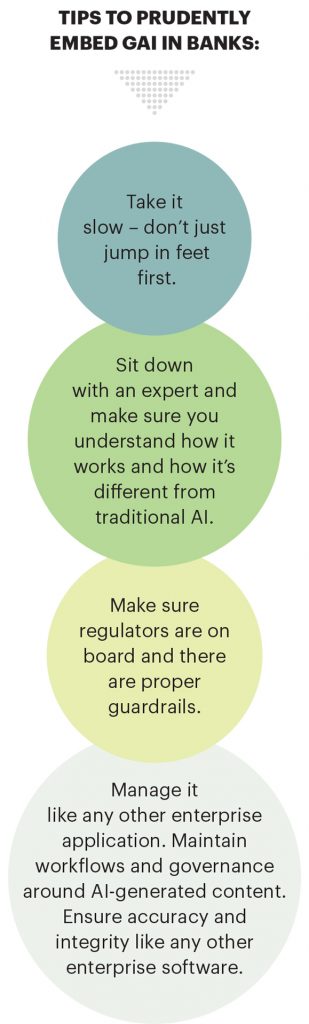

We have thus far only skimmed the surface of the things GAI can do and mistakes will surely be made as we explore this new territory. Forward-thinking banks may stand to benefit greatly from harnessing the capabilities of GAI, but whether they can do so safely remains to be seen. The question for banks is not ‘if’, but ‘when’ their employees and customers start to use this technology…are they ready?

Dr Amanda Salter is Associate Director at Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm. She has delivered award-winning customer experience strategies for the Fortune 500 and been an Agile practitioner for over a decade. Previously with Accenture’s London office, Dr Salter holds a PhD in Human Centred Web Design; BSc (Hons) Computing Science, First Class; and is a certified member of the UK Market Research Society and Association for Qualitative Research.