The Heat Is On

Be ready for more prescriptive climate regulation in finance.

By Julia Chong

In line with the United Nations’ call in this Decade of Action – a global push from 2021 to 2030 to accelerate sustainable solutions to humanity’s biggest challenges, from poverty and equity to food security and continuing environmental degradation – financial regulators are upping the ante on what’s needed to tackle climate change.

Climate-related risks are now considered to be material risks that can impact the financial, reputational, and strategic operations of banks. Concrete moves are underway for more in-depth assessment and disclosure through – amongst other steps – increased Pillar 2 capital requirements, more granular climate stress test scenarios at major jurisdictions and other increased measures as emerging research point to potential material losses in the financial system if climate change is left unaddressed.

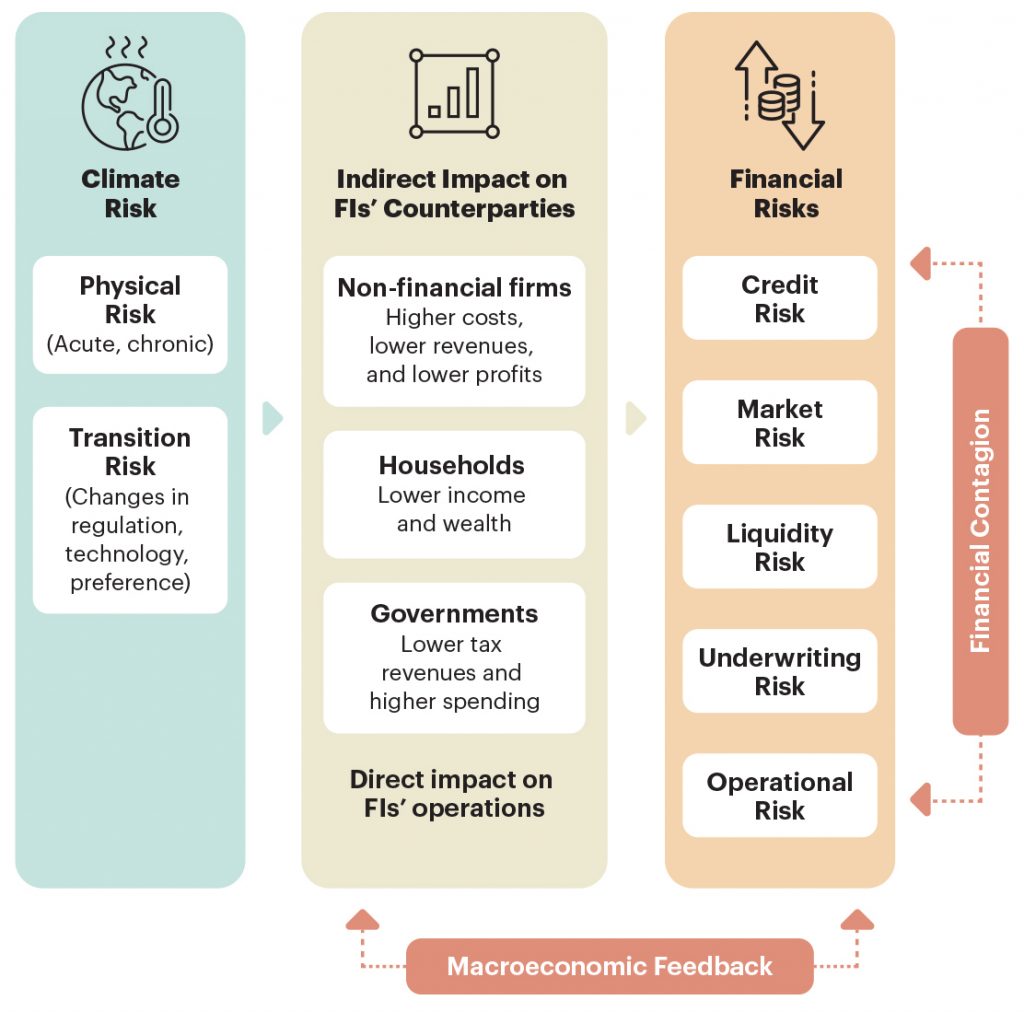

Figure 1 expands on the physical and transition climate risks and how these can affect banks’ viability, whether directly or through counterparties, and potential financial contagion.

Regulators in major jurisdictions continue to toughen their stance in favour of mandatory and standardised climate disclosure frameworks, common taxonomies to delineate green/brown activities and, increasingly, climate stress tests.

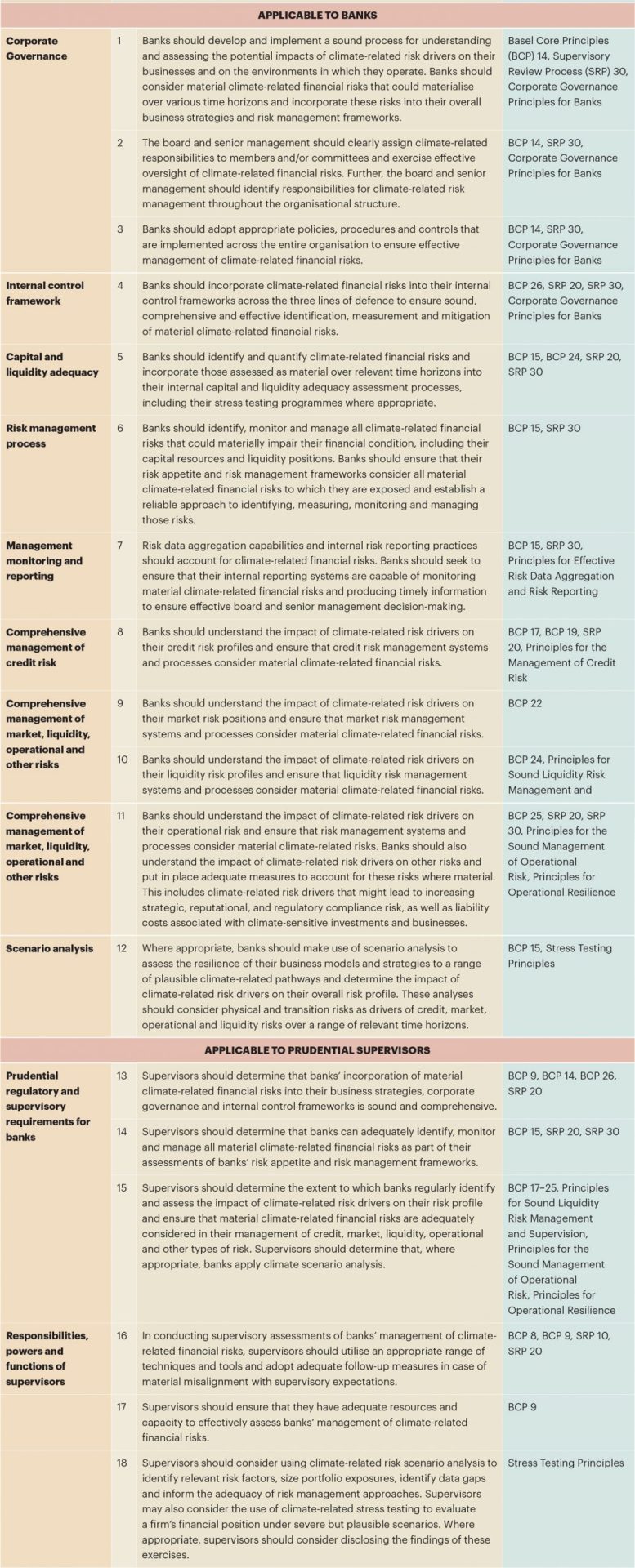

The major principles and practice for climate-related risk management are expressed through three Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) documents: Principles for the Effective Management and Supervision of Climate-related Financial Risks issued in June 2022; Climate-related Financial Risks – Measurement Methodologies and Climate-related Risk Drivers and Their Transmission Channels, both issued in April 2021.

The 18 high-level Principles (12 for banks, six for prudential authorities) were devised “to strengthen the regulation, supervision and practices of banks worldwide with the purpose of enhancing financial stability”, the aim being to put to rest any remaining ideological opposition within the industry to the impact climate change can have on the global financial system if left unaddressed. Figure 2 is a summary of the Principles and provides a birds-eye view of the global priorities that currently govern all financial institutions, yet it must be approached as an evolving standard as climate regulation is peppered with emergent risks. In the long run, a culture of adaptability and agility will serve banks best.

This has prompted prudential authorities to introduce new and/or more granular requirements for banks conducting scenario analyses and stress tests, such as changes to the scenario designs and increasing the time frames for forecast. Most jurisdictions are slated to conduct their 30-year climate stress tests within the next 12 months, exercises that will undoubtedly assist regulators and financial institutions to fill in many data and process gaps in the transition to net zero.

Asia-Pacific regulators have issued guidance notes and policies that are aligned to the BCBS, albeit with differing degrees of coverage and implementation.

In Malaysia, the Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) directive is clear. Its latest Policy Document on Climate Risk Management and Scenario Analysis, issued on 30 November 2022, set future expectations that financial institutions should tackle the looming threat that climate change poses to financial stability by:

+ urgently taking early actions to implement changes towards building climate resilience;

+ strategically accounting for how actions today affect future outcomes under a range of scenarios and time horizons over the long term;

+ comprehensively strengthening the risk management frameworks to address these financial risks from climate change. In particular, financial institutions are to manage these risks by recognising the distinctive two elements of climate-related risks: far-reaching in breadth and magnitude, foreseeable but highly complex due to uncertainty, nonlinearity, irreversibility and dependency on short-term actions; and

+ holistically managing the systemic impact of climate-related risks. Financial institutions stand to gain from greater collective coordination and harmonisation, notably through industry-wide platforms, including those facilitated by the Joint Committee on Climate Change and VBI Community of Practitioners.

The policy uniquely presents a Malaysian-specific context for banks and how climate-related risks should be an integral part of every financial institutions’ governance, risk management, ICAAP, scenario analysis, stress testing and disclosure practices.

Parallel to this is the AICB’s Certificate in Climate Risk (CICR), a new programme developed by the Chartered Body Alliance comprising the Chartered Banker Institute, UK; the Chartered Insurance Institute, and the Chartered Institute for Securities & Investment.

Comprising a vast range of developments in climate change and its impacts, the CICR programme focuses on the evolving policy and regulatory landscape relating to climate risks and how finance is tackling the sustainability challenge head-on by:

In December 2021, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) introduced a new module, GS-1: Climate Risk Management requiring authorised institutions (AIs) in the city-state to begin incorporating “sound practices supporting the transition to carbon neutrality”. Although classified as a non-statutory guidance note, GS-1 forms part of the Supervisory Policy Manual issued by the regulator to “set out the HKMA’s approach to, and expectations in, reviewing AIs’ climate-related risk management”.

Concurrently, the prudential authority reported on the outcomes of its pilot sector-wide climate risk stress test (CRST) exercise, which sought to assess the climate-resilience of the city-state’s banking sector and facilitate capacity building in the climate risk management practices of participating banks. Comprising 20 major retail banks and seven branches of international banking groups, the pilot CRST accounted for 80% of the sector’s total lending and stress-test resilience under three scenarios:

Results of the CRST showed:

In a January 2023 article with Risk.net, counsel Wei Na Sim at legal firm Meyer Brown said that the HKMA plans to adopt a more prescriptive approach in CRSTs scheduled in 2023 and 2024, with more granular scenario specifications and possible Pillar 2 capital measures.

A concentration of activity is already underway as the climate risk reporting regime broadens in both granularity and reach. There are immediate priorities to be addressed at banks of all sizes, beginning with the boardroom and right down to front-line staff.

For finance to contribute in bringing down global temperatures, it needs to first ‘turn up the heat’ in its own house through effective climate compliance.

Julia Chong is a content analyst and writer at Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm.