Ready to Face the Wind

Fortune doesn’t always favour the bold.

By Angela SP Yap

What is the cost of overconfidence?

Since 2008, economic researchers have sought to understand why some banks suffer more than others during a crisis. Contagion is always a risk when there is a shock to the financial system, however the sensitivity of each financial institution to a crisis seems unpredictable – some banks emerge unscathed, others surface with minor scratches, whilst a few never recover.

A growing body of research point to managerial overconfidence, or more specifically CEO overconfidence bias, as a determining factor in the banking sector.

Overconfidence bias is the tendency for us to think that we are better than can be objectively proven. For instance, it is likely that we think we are better drivers than we actually are. But when was the last time you got into an accident in your vehicle?

In finance, such cognitive bias manifests as an overestimation of one’s financial acumen, excessive risk-taking, a disregard for objective data and advice, imprudent decision-making, and suboptimal performance.

History is littered with costly examples of such hubris, to which finance is no exception.

Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman, who has led the cognitive revolution in social psychology over the past 40 years, found that individuals often fall victim to ‘positive illusions’ – unrealistically positive views of one’s abilities and character, the illusion of control, unrealistic optimism – all of which promote hawkish decision-making.

His article with Jonathan Renshon on Why Hawks Win explains that decision-makers hold “a bias in favour of hawkish beliefs and preferences [that] is built into the fabric of the human mind.”

“Our conclusion is not that hawkish advisors are necessarily wrong, only that they are likely to be more persuasive than they deserve to be.”

This explains why humans frequently favour extroverted leaders and bold strategies even when it no longer brings net benefit to society. Whether in political or financial warfare, the science behind social psychology is consistent: Our brain chemistry makes us inclined towards those who exhibit overconfidence, whether or not their track record holds up to scrutiny.

How does this impact the financial sector?

Research published in the July 2022 edition of the International Journal of Finance and Economics adds to our understanding of financial resiliency by directly measuring each banks’ contributions to a systemic event.

Whilst previous studies addressed the impact of overconfident CEOs on lending standards and loan-loss provisions, authors Liang Liu of Beijing-based energy and commodity group Mercuria together with the University of Nottingham’s Hang Le and Steve Thompson, found that CEO-biased beliefs have ripple effects “well beyond the firm’s boundary”.

Their work, CEO Overconfidence and Bank Systemic Risk: Evidence from US Bank Holding Companies, is the first to prove that the overconfidence bias amongst the top decision-makers of financial institutions pose a real threat to financial resilience.

“Our empirical analysis of US bank holding companies shows that on average, banks with overconfident CEOs have higher systemic risk, both measured as the ex ante average dollar loss in market capitalisation during the worst 5% of market return days and as the ex post losses during the 2007–2008 crisis, compared to banks with non-overconfident CEOs. Banks with overconfident CEOs also have higher holding of private mortgage-backed securities and higher leverage.

“In the aftermath of the financial crisis, fewer CEOs are classified as being overconfident but we find no evidence of a structural break in the relationship between CEO overconfidence and bank systemic risk.”

“Our results therefore have an important implication: overconfidence bias among banks’ top decision-makers may impose costly externalities to the financial sector and the rest of the economy.”

This is an important point for us to hold on to, especially as investors pivot towards Asia.

Today, Asia-Pacific banks rank among the world’s most resilient. With above-minimum capital adequacy ratios, strong balance sheets, and relative agility, analysts are in consensus that its financial institutions are better positioned to overcome disruptions from tech and comply with more assertive regulation.

However, it’s crucial we remember that just months before the global financial crisis erupted, global rating agencies and research houses like Moody’s cautioned against the Asian banking sector’s “exuberance” as the data pointed to a “certain overconfidence” in the financial sector.

A post mortem by the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ on Why Did Asian Countries Fare Better During the Global Financial Crisis than During the Asian Financial Crisis? reminds us: “The fact that Asia largely averted financial instability in the face of a full-blown global financial crisis is no cause for hubris or overconfidence. In fact, in 1997–98 Asia had suffered a devastating financial crisis of its own. That crisis brought the region’s financial markets to their knees as stock markets and currencies collapsed. The crisis soon spread to the real sector, pushing the economy into a deep recession and putting millions of Asians out of work. Although the region staged a V-shaped recovery in 1999, the crisis was a game changer that put a rude stop to the vaunted ‘East Asian miracle’.”

A timely reminder as jurisdictions across the world embark on the arduous task of strengthening the resilience of their economies through the mandated development of recovery and resolution plans for financial institutions.

In a precursor to the invasion of Iraq, when questioned about the lack of evidence regarding the supply of weapons of mass destruction, Donald Rumsfeld, the then US Secretary of Defence, (in)famously said:

“As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.”

As convoluted as it sounds, Rumsfeld’s point about ‘unknown unknowns’ harkens to a technique, the Johari Window, which is used by self-help instructors and corporations to increase their trust quotient and improve relationships.

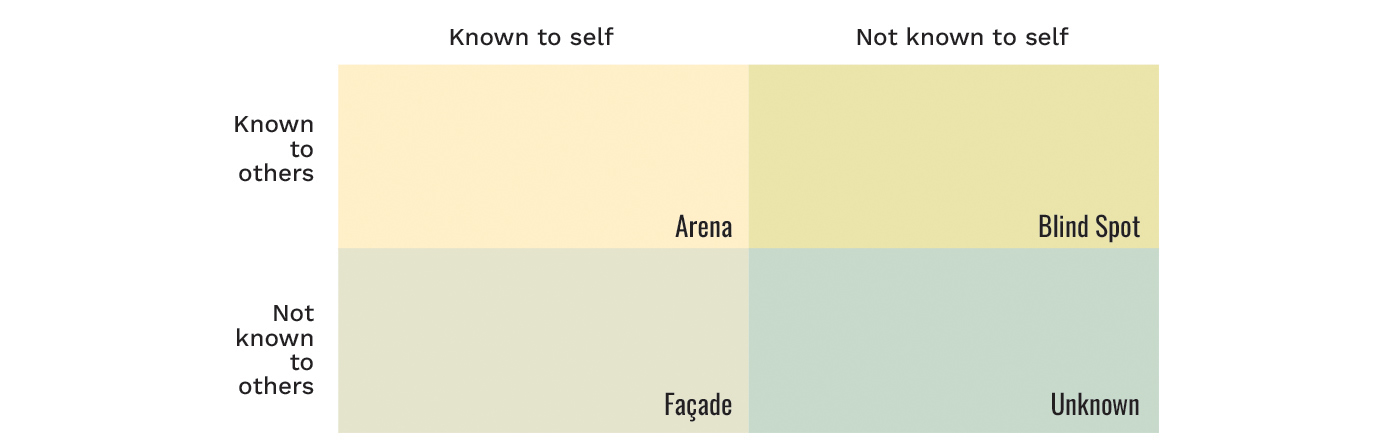

Developed by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham in 1955, this heuristic exercise is a model on how to build a personality map for awareness. It comprises four viewpoints (Figure 1) and relies on a feedback/disclosure model in which trust is built in two ways: firstly, by revealing information about yourself to others; secondly, by learning about yourself from external feedback.

Although the Johari Window has been nudged aside in recent decades by ‘sexier’ analytical frameworks, for me, it stands as one of the quickest and most effective tools for self-awareness and trust building, no matter which rung of the ladder you are at in life or work.

It is also satisfying to see its principles applied within the financial circuit, especially by prudential authorities who play a critical role in setting the tone at the top.

This is the question which Michael S Barr, Vice Chair for Supervision at the Federal Reserve, answered in the aftermath of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failure.

The frank critique and self-awareness of the Fed’s institutional flaws, outlined in his letter accompanying the Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank which was released this April, is an eloquent and rare departure from the PR spiel that prevails in regulator-issued communications. It is, if nothing else, an archetype strategy where self-awareness morphs into effective communications:

“We need to develop a culture that empowers supervisors to act in the face of uncertainty. In the case of SVB, supervisors delayed action to gather more evidence even as weaknesses were clear and growing. This meant that supervisors did not force SVB to fix its problems, even as those problems worsened.

“[W]e need to guard against complacency. More than a decade of banking system stability and strong performance by banks of all sizes may have led bankers to be overconfident and supervisors to be too accepting. Supervisors should be encouraged to evaluate risks with rigour and consider a range of potential shocks and vulnerabilities, so that they think through the implications of tail events with severe consequences.

“Contagion from the failure of SVB threatened the ability of a broader range of banks to provide financial services and access to credit for individuals, families, and businesses. Fast and forceful action by the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Treasury Department helped to contain the damage, but weaknesses in supervision and regulation must be fixed.

“In doing so, we should be humble about our ability — and that of bank managers — to predict how losses might be incurred, how a future financial crisis might unfold, and what the effect of a financial crisis might be on the financial system and our broader economy. Greater resilience will guard against the risks that we may not fully appreciate today.

“This report is a self-assessment, a critical part of prudent risk management, and what we ask the banks we supervise to do when they have a weakness. It is essential for strengthening our own supervision and regulation. I am grateful to the staff who conducted the review and prepared the report.

“I also appreciate that others will have their own perspectives on this episode. We welcome external reviews of SVB’s failure, as well as congressional oversight, and we intend to take these into account as we make changes to our framework of bank supervision and regulation to ensure that the banking system remains strong and resilient.”

It is prudent for us to take a page out of this playbook; when faced with a crisis, one should not be too proud to admit that they are part of the problem.

It is the only way to travel in a brave, new world.

Are you ready to face the wind?

Angela SP Yap is a multi-award-winning social entrepreneur, author, and financial columnist. She is Director and Founder of Akasaa, a boutique content development and consulting firm. An ex-strategist with Deloitte and former corporate banker, she has also worked in international development with the UNDP and as an elected governor for Amnesty International Malaysia. Angela holds a BSc (Hons) Economics.