AI Dominance and its Regulation in ASEAN

How a region can embrace its differences and rise to the occasion.

How a region can embrace its differences and rise to the occasion.

By Julia Chong

By Julia Chong

In a recent white paper, the World Economic Forum reports that financial services firms spent USD35 billion on artificial intelligence (AI) in 2023. This figure is set to nearly triple to USD97 billion by 2027 with projected investments across banking, insurance, capital markets, and payments businesses. What these numbers do not reflect are the undercurrents that have propelled its development.

The race for domination of AI technology is intrinsically linked to the geopolitics of the day. In late January 2025, DeepSeek – China’s low-cost, open-source, locally developed AI platform – came out of nowhere to unseat deeply held assumptions about the US’ dominant position in the technology.

Within hours of the launch of DeepSeek’s chatbot version R1, traders on Wall Street began panic-selling big technology stocks such as chipmaker Nvidia, wiping USD1 trillion off the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index by the end of the trading day. This marked the biggest single-day loss in the history of the exchange.

In the weeks that followed, Alibaba and ByteDance released their respective AI models on similarly ‘cheap and cheery’ budgets, efficiently deploying them on websites, mobile apps, chatbots, and other platforms. This more than buoyed the stock market – the Hang Seng Tech Index is up 37.8% year to date with AI stocks leading the charge.

Based in Hangzhou, DeepSeek’s founder, Liang Wenfeng, has been hailed as a national hero for giving China its competitive edge over the US. However, it is unlikely that an entrepreneur like Liang “came out of nowhere” (as several news portals described it) to topple the idea of American supremacy in AI.

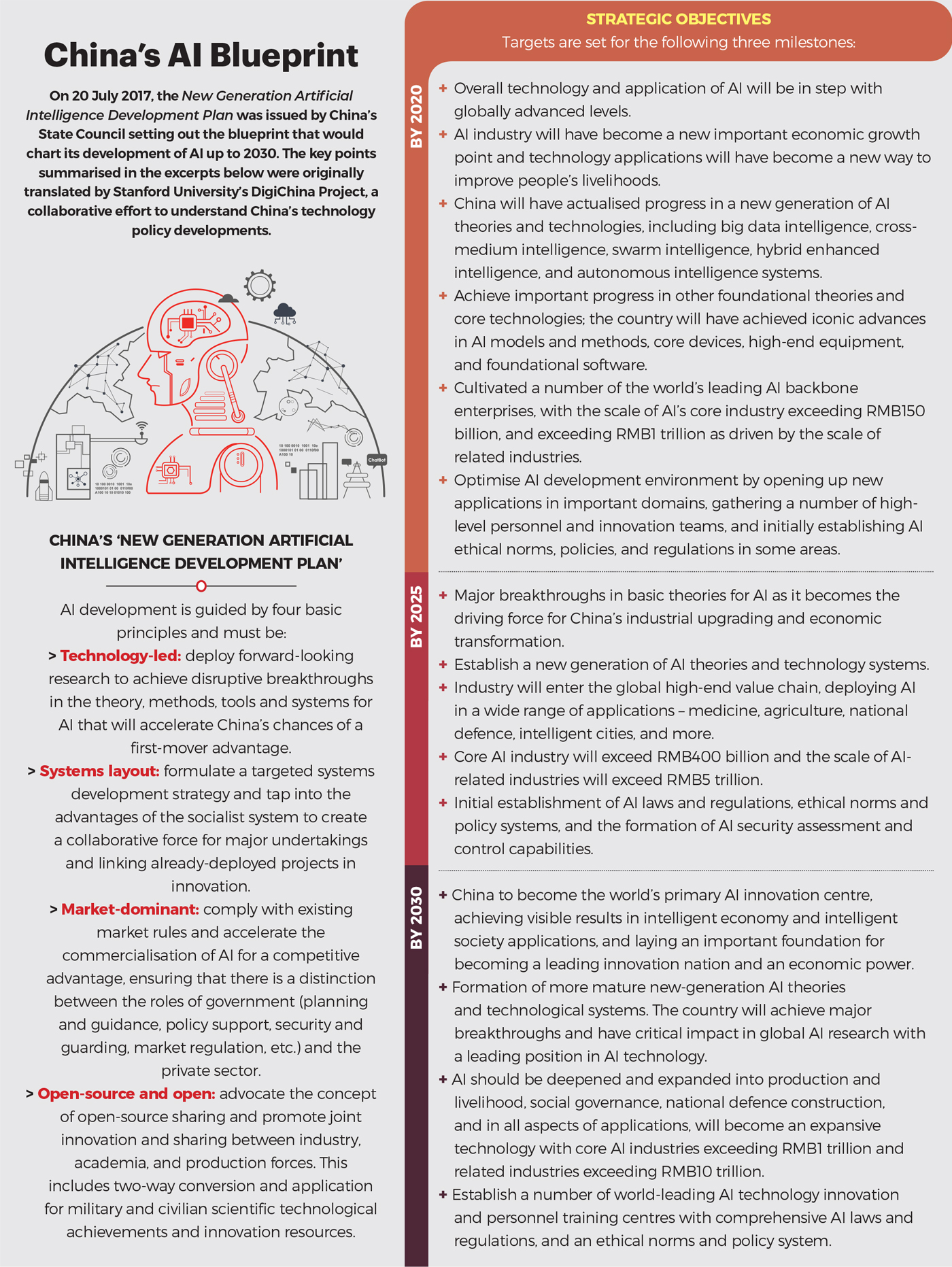

For decades, China has been strategically working to seize pole position in AI development. Its aspirations are expressed in A New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, a landmark document issued in 2017 by the State Council which outlines the principles as well as resources that will be dedicated towards achieving this goal by 2030.

China’s AI Blueprint on page 19 summarises the key drivers behind the state’s development of this technology and some broad-based targets, which will be of use to those who wish to assess for themselves whether China’s trajectory has matched its initial plan in 2017 and gauge if the state will achieve its aspirations within the next five years.

According to a feature by The Banker in late March, China has recently called on its companies to become “domestic national champions” of DeepSeek, and as many as 20 banks have heeded this call and applied the technology, albeit conservatively.

Other reports, including advertorials, cite AI use cases at some of the republic’s top state-owned and joint-stock banks. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s AI-based applications included algorithmic credit advisors and intelligent risk detection; Bank of China deployed DeepSeek R1 to generate its research output; China Construction Bank’s in-house engineers built a Model-as-a-Service platform to power everything from credit analysis to knowledge retrieval.

Yet, in recent months, news has begun trickling in that the results of these massive AI-based deployments are falling short of expectations and returns. Yicai Global, the English-language arm of the financial news group in Shanghai, wrote: “Chinese banks rushed to embrace artificial intelligence but have been disappointed by the results despite making massive investments, leading many to rethink and refine their AI strategies toward more specialised, scenario-tailored solutions, according to people in the banking and financial technology sectors.”

The same news report quotes several C-suites. Meng Qian, Chief Information Officer at the Bank of China, attributed the lacklustre performance of AI-based systems to their limited depth of financial understanding as “financial knowledge makes up only about 5% of pre-training data in foundational models”. Hu Debin, Vice President at Bank of Shanghai, cites cost as another burden that disproportionately hits small- and medium-sized banks as large language models (LLMs) like DeepSeek “require substantial capital and manpower from purchase and deployment to maintenance and optimisation” with no guarantee that the model will fulfil its potential.

Academics also shared their views in the Yicai report: “[Dr] Fang Yu at CEIBS [China Europe International Business School] said the notion of solving every problem with one monolithic model is clearly flawed, adding that big banks should avoid blindly adopting off-the-shelf LLMs and focus on building smaller, purpose-built models tailored to their unique business needs.”

“Zhao Liming, Director of the Digital Finance Centre at Kunming-based Fudian Bank, echoed this view. He suggested that small- and mid-sized banks leverage local data and internal resources to fine-tune their own models for better outcomes.”

The intensifying competition between China and the US for dominance in the AI sphere brings with it global implications:

Major regulatory developments have since taken place across several jurisdictions and/or economic blocs.

The European Union’s AI Act came into effect on 1 August 2024 with a phased-in approach that began in February 2025 and full compliance scheduled for 2 August 2026. Described as ‘ground-breaking’ when it was first passed in Parliament, the EU standard sets out a risk-based AI classification system according to its use and the risks each application type pose to users. Different risk levels correspond to either more or less stringent AI compliance requirements.

ASEAN’s approach to governing AI reflects the diversity of the region and presents a compelling case of how it is possible to chart differentiated ways forward and still work together towards regional stability and security.

The ASEAN Guide on AI Governance and Ethics, a regional framework for responsible AI development and deployment, was endorsed by the ASEAN Digital Ministers in February 2024 in order to build trust in AI by encouraging responsible practices. Its approach is mostly market-driven and recommendations are voluntary. This gives room for each member state to develop national-level AI strategies, regulations and/or guidelines to suit their respective contexts.

Singapore’s regulatory response remains light-touch and has been touted to be the middle-ground for standard-setting, a credible and potential way between the US’ deregulatory pivot and the EU’s high-compliance model. This approach could serve as a model for the rest of Asia Pacific. Although the city-state does not have an overarching legislation governing AI use – opting instead to examine AI use cases through the lens of existing laws such as data protection, intellectual property rights, and consumer affairs – its Model AI Governance Framework aligns with global best practices.

In Malaysia, the National Guidelines on AI Governance and Ethics is the framework leading towards responsible and ethical AI development and deployment. Under the purview of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, it is a non-binding framework aiming to provide guidance through its seven core principles of fairness; reliability, safety and control; privacy and security; inclusiveness; transparency; accountability; and pursuit of human benefit and happiness. The country’s National AI Office was established on 12 December 2024 and is tasked with shaping AI initiatives, policies, governance, and investment strategies, including an action plan from 2026–2030, code of ethics, and public sector guidelines for use.

Indonesia is fast-tracking its AI legislation. This follows the launch of a new sovereign wealth fund, Daya Anagata Nusantara or Danantara, by President Prabowo totalling USD900 billion which will be invested in 20 or more high-impact national projects, including into AI technology to develop its own DeepSeek-like platform and the building of an AI centre.

Although in its relative infancy, Vietnam is charting its unique way forward with proposed guidelines that blend the EU’s risk-based classification and penalty systems with China’s state-led governance and restrictions.

As the world navigates its way through this new technological frontier, the ASEAN process is a prime example of how a region can embrace its differences and rise to the occasion.

Julia Chong writes for Akasaa, a strategic consulting and publishing house with offices in the UK, UAE, and Malaysia.